Middle Childhood Development

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Physical and Cognitive Development

Chapter Focus Question:

What are the most significant changes that children go through in middle childhood, and how do these set the stage for adolescence?

- Independence

- Motor development

- Muscle size

- Cognitive development

- Concrete operations

- Piaget

- Conservation

- Reversibility

Section Focus Question:

How do motor development and sophisticated concepts such as concrete operations and conservation increase children’s independence?

Key Terms:

Middle childhood, roughly encompassing ages six through twelve, is dominated by changes in physical and cognitive capacities and emotional development. Parents often report a surge of independence in their child during this period of development because children are bigger, stronger, and endowed with more endurance than when they were younger.

Children exhibit noticeable improvements in motor development as they refine coordination needed for running, throwing, catching, balance, and agility. One reason for this motor development is the normative changes in biological size. During middle childhood, increases in muscle mass help make boys and girls stronger. How much growth in height and weight a child will undergo has a lot to do with genetic factors — children tend to be similar sizes and heights as their parents. However, the environment also plays an important role. More frequent opportunity to engage in sports and other physical activities increases motor skills whereas poor nutrition and inactivity impedes them.

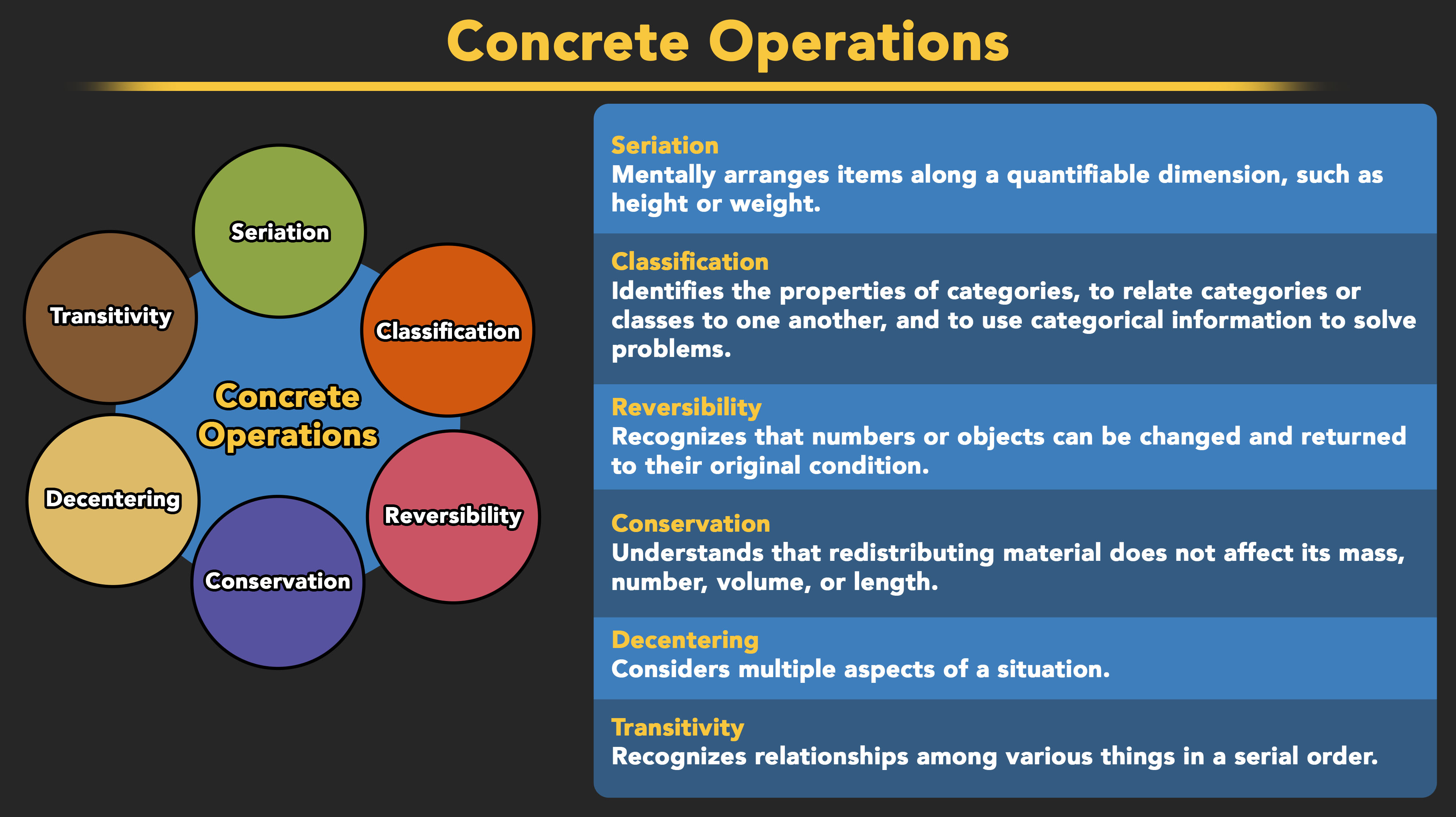

Along with physical development comes marked improvement in cognitive development. During middle childhood, children have increasing understanding of their own thoughts and actions. Piaget referred to this phenomenon as the “concrete operations” stage in which children begin to engage in mental operations that allow them to combine, separate, order, and transform objects and actions. For instance, Piaget observed that children can consider more than one attribute of an object at one time and understand that certain properties of an object will remain the same even when other ones are altered. The classic example of this is the concept of “conservation” whereby a child will understand that when liquid is transferred from a tall, thin glass to a short, thick glass the amount of liquid remains the same.

During the concrete operations stage children also begin to communicate more effectively about objects a listener cannot see and can think about how others perceive them. This aptitude allows children to relay stories to parents about the events of the day, for example.

- Metacognition

- Goal-oriented behavior

- Metacognitive regulation

- Metacognitive knowledge

- Memory strategies

- Working memory

- Attention span

- Memory and attention

Section Focus Question:

Why is metacognition key to planning and learning?

Key Terms:

Progressively sophisticated planning abilities emerge during middle childhood. To make a plan, the child needs to be able to hold in line what is presently happening, what they want to happen in the future, and what needs to get done in order to draw a link between the present and the future. Once children reach this developmental milestone, they start to exhibit “goal-oriented behavior.” Scholars William Gardner and Barbara Rogoff studied this phenomenon by asking groups of four- to six-year-olds and seven- to ten-year-olds to solve mazes using pen-and-paper tests. They found that the older age group tended to plan their route ahead of time whereas the younger group just dove right into the problem without planning ahead.

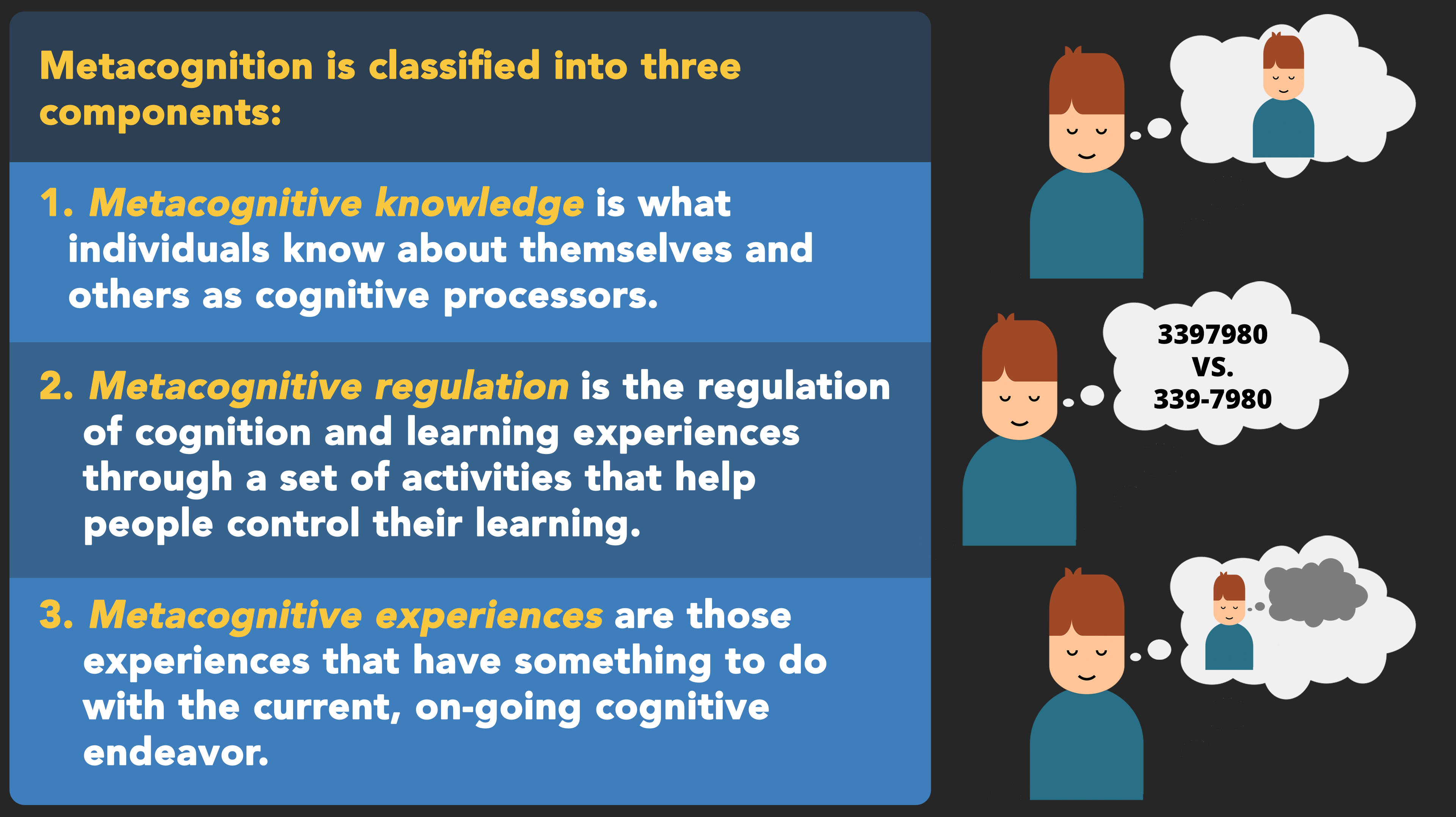

Planning and goal-oriented behavior is related to “metacognition,” the awareness and understanding of one’s own thoughts. This skill is important because it helps children identify the limits of their knowledge and problem-solving skills. It is perhaps for this reason that children show an uptick in questions about the world around them. Anyone who has spent considerable time with a child in this age group is familiar with the many “why?” questions they ask.

Researchers at Yale University tested metacognition in kindergartners, second-graders, and fourth-graders by asking each child to rate their understanding of appliances, such as toasters, on a five-point scale. In line with the idea that younger children overestimate their knowledge because they lack metacognition, kindergarteners were more likely to rate greater knowledge about toasters than fourth graders (with second graders’ ratings somewhere in-between). Amusingly, kindergarteners’ ratings of their toaster knowledge actually increased after an actual toaster expert described how toasters work.

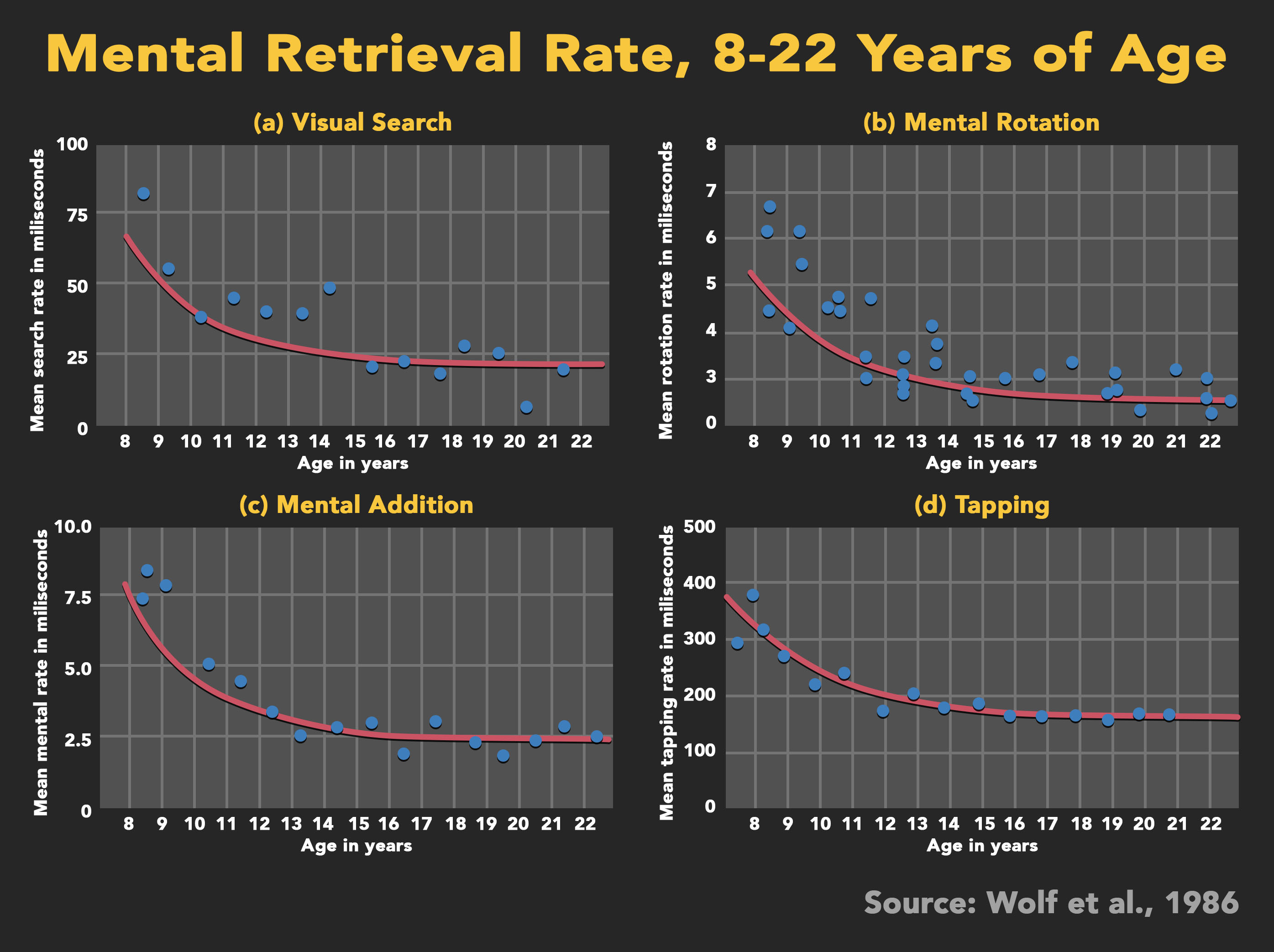

A somewhat distinct view from Piaget’s theories are those put forth by “information-processing theorists.” These theorists attribute increases in cognitive development during middle childhood to improved memory and attention capabilities.

Extensive research shows that children in middle childhood have better “working memory” than younger children. Most pre-kindergarten children can recall four items from a string of numbers presented to them whereas most 10-year-olds can remember about six. Brain development of regions important for memory likely contribute to this effect but new “memory strategies” (the purposeful use of tricks to boost recall such as rehearsal) are also important.

Attention is a close cousin of memory, and it too improves significantly during middle childhood. Children are better able to stay focused and ignore irrelevant distractions as they get older. This skill has obvious implications for classroom learning but also has positive consequences on social learning from peers and parents.

Memory and attentional development help children acquire the building blocks of the most significant occurrence in middle childhood: learning to read and write. The phonological awareness and understanding of semantics and grammar that begins in early childhood is called upon heavily once children begin attending school. The ability to string together words and sentences to read and write stories is an important communication skill that is a major contributor of future success.

- Kindergarten readiness

- Moral development

- Perspective taking

- Secure attachments in infancy

- Emotional development

- Social development

- Autism Spectrum Disorders

- The power of self-esteem

- Biological and environmental influences on human development

Section Focus Question:

Biological and environmental factors shape a child’s experiences, but how do we know when a child is ready to have meaningful social relationships?

Key Terms:

In the United States, children begin elementary school around their fifth birthdays. How was it determined that this age is when children are "ready" for kindergarten? Kindergarten “readiness” refers to a time when the child's physical, cognitive, social, and emotional maturity are sufficient enough to handle more complex learning and activities.

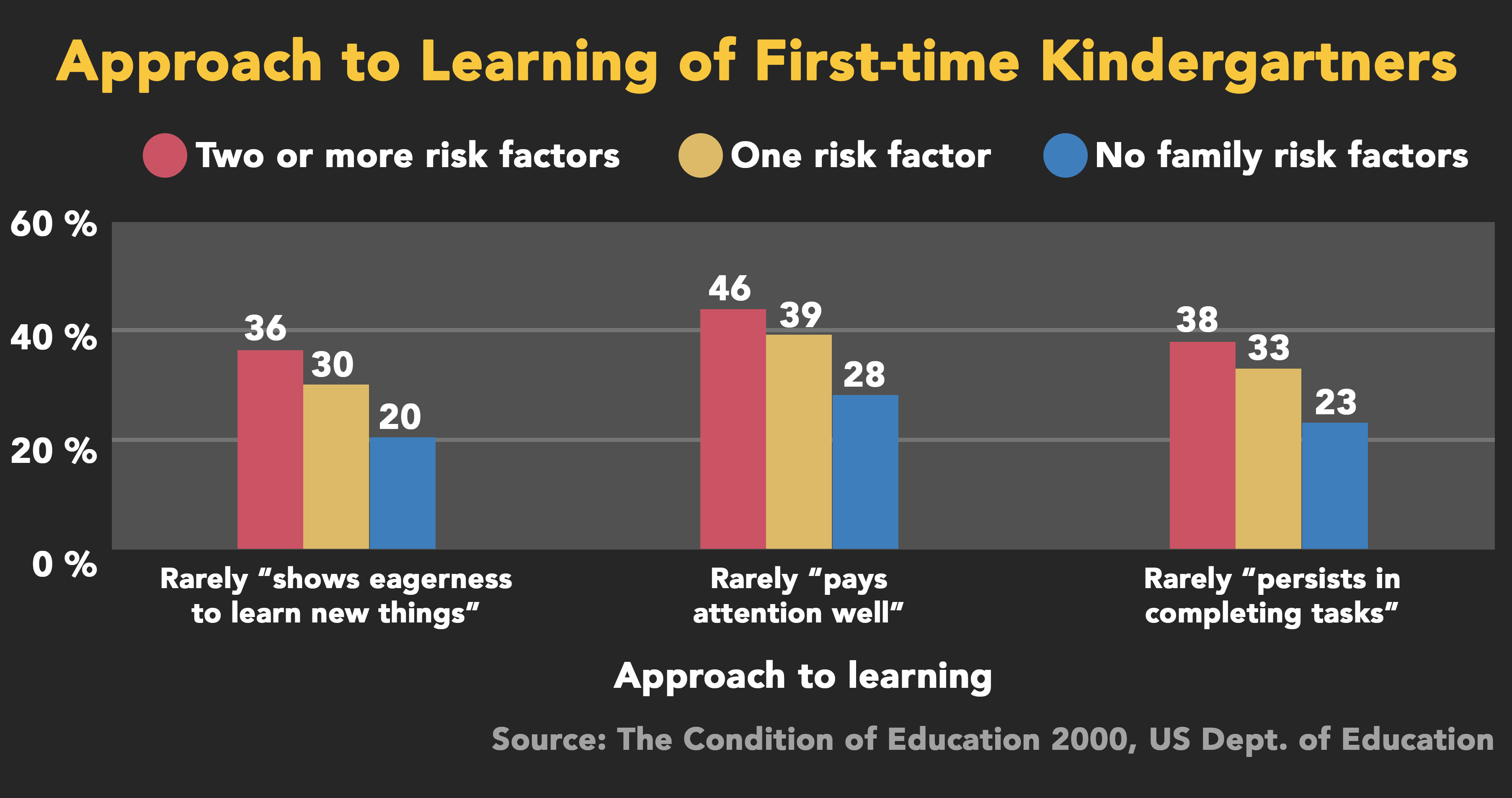

In 2000, the US Department of Education conducted a study on more than 19,000 kindergartners across the country. Children were assessed on their reading, math, and general knowledge skills as well as their physical, motor, and social development. The study found that kindergarten readiness more largely determined physical health (how well-rested and well-nourished the child is), communication skills, and learning interest (following directions and exhibiting curiosity to learn) than by knowing specific skills (e.g. holding a pencil or knowing the alphabet). These findings and teacher reports underscore the importance of being able to hold attention, express one's emotions and thoughts, and demonstrate a good working memory.

Emotional Development

Emotional development occurs throughout the lifespan as individuals acquire new abilities to understand emotional and social meaning, and with changes in the brain regions that underlie processing of emotions. However, there are particular emotional developmental milestones that occur in middle childhood.

As children become more self-aware they have an increasingly sophisticated understanding of how they relate to others. Indeed, changes in the child’s ability to understand and follow societal norms and expectations are manifested in moral development. Moral development refers to the internal notions of right and wrong in making moral decisions.

An interest in peers grows considerably during middle childhood as children establish bonds with friends. These bonds help children learn and improve social cognitive abilities. As they interact with friends, there are changes in “perspective taking” skills such that they come to realize that friends may have different habits, customs, and viewpoints from their own. Those who are considered more attuned to the concerns or perspectives of others are more likely to form and maintain friendships.

With close friends, children share secrets and private jokes, feel accepted, and even learn how to "agree to disagree" with others. As such, close friends in childhood play a pivotal role in setting children up to implicitly learn the social norms that govern adult relationships. Perhaps most importantly, they provide children with a sense of belonging and the positive feeling of being emotionally bonded to another person.

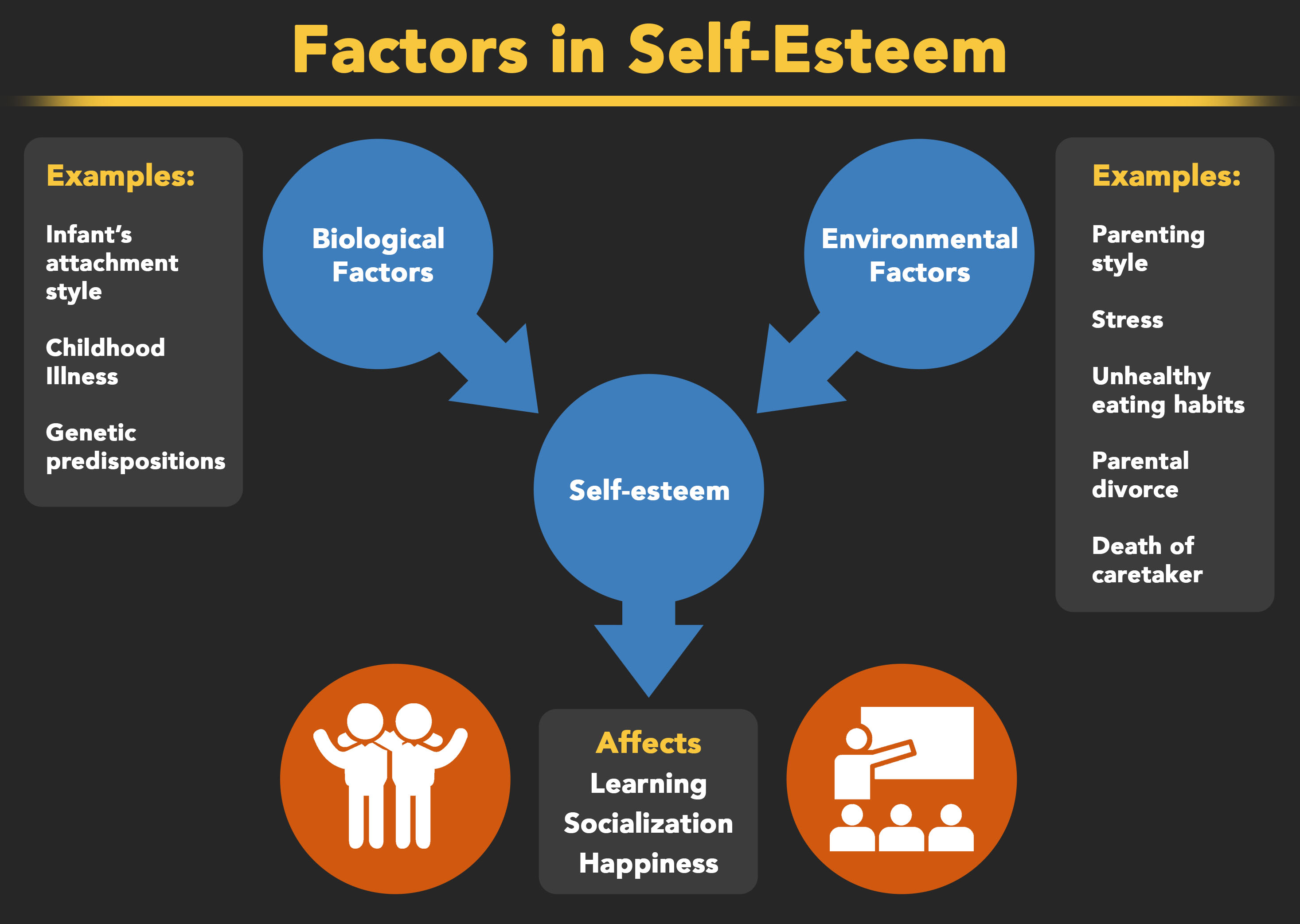

It is perhaps no coincidence that greater interactions with others also bring about evaluations about the self, commonly called “self-esteem.” The need to protect and enhance one's self-esteem is considered a basic psychological motive that drives behavior. Each person varies slightly in the variables they use to calculate their own self-esteem but many base it on feelings of love, worth, support, and approval from others. A child who consistently receives encouraging reactions to athletic prowess or astute problem-solving skills is more likely to have healthy self-esteem than someone who feels as if he or she does not have strong skills in anything.

The importance of healthy self-esteem is evident not only when a child is excelling at a particular behavior or skill but also when he or she is struggling or failing. Children with high self-esteem do not generally become disenchanted or overly upset by a failure. Instead, their high self-esteem serves as a protective shield that allows for a greater probability of learning from the failure and focusing on attributes in which they do excel. In contrast, people with low self-esteem struggle to "bounce back" when they experience failure. Negative feedback is so painful for them that they actively avoid trying new things because they feel vulnerable, and avoid comparison with others.

The influence of peers and one's own self-reflection is important for emotional development, but parents and families play a continued role in helping children thrive socially and emotionally. As mentioned earlier, having a secure attachment to caregivers early on sets the stage for bonding with others as children start to form friendships. Children who have secure attachments in infancy are more popular in preschool and elementary school and are more apt to approach new social situations with confidence.

Interestingly, how a mother disciplines and talks to her child is associated with the child's social competence and popularity. Children who learn that the best way to resolve conflicts is through aggressive behavior are more likely to be aggressive and have peer conflict at school. In contrast, children who learn that working through conflicts in agreeable ways that involve compromise, perspective-taking, and compassion have an easier time establishing and maintaining friendships. One study found that children who report that their parents do not resolve conflict well also have difficulty resolving conflicts in their own close friendships.

In sum, biological and environmental factors contribute to the immense cognitive and emotional changes that occur in middle childhood.