Principles of Social Psychology

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

What insight does the study of social psychology bring to our understanding of how the people around us impact our experience of the world and how we live our lives?

- Social psychology

- Social behavior

- Social influence

- Social pressure

- Conformity

- Metaphor of the Mask

- Persona

- Stanford Prison Experiment

- Sadism and depression

- Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Section Focus Question:

How have the results of the Stanford Prison Experiment shaped the study of social psychology, and how do social pressures and influences overwhelm individuals’ pre-existing values and beliefs about themselves?

Key Terms:

Social psychology is the scientific study of social influence. It offers key insights into human nature by focusing on how other people impact the way we think, how we feel, and what we do. The first principle of social psychology is that it focuses on studying how social influence affects our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. The second is that it uses the scientific method to explore social behavior.

Social influence can come in many forms, including the social norms and values that we have grown up with, real or perceived pressure to go along with those around us, and the social roles we play throughout life, such as son or daughter, student, friend, employee. The social psychological perspective emphasizes how the people around us can have a powerful but unrecognized impact on how we experience and move through the world. Social psychologists often talk of the powerful influence of social roles on our behavior as the Metaphor of the Mask.

One often-cited and controversial, study demonstrating the power of social influence is the Stanford Prison Experiment, conducted by Philip Zimbardo in 1971. In this study on the psychology of prison life, 24 psychologically healthy college-aged men, who were chosen from a larger initial volunteer pool, were randomly assigned to play the role of guard or prisoner in a mock prison. The guards were instructed to maintain order while also being aware of the possible seriousness and dangers of the situation. But they were given little guidance or specific training on how to manage the prisoners.

The Stanford Prison Experiment

At the start of the experiment, prisoners were surprised to be arrested at their homes by actual police officers, and then taken to the mock prison. The prison admission procedure was designed to degrade and humiliate the prisoners in a manner that mimicked real prisons. This included being strip-searched and “deloused” with insecticide to convey the idea that they were somehow contaminated.

Both prisoners and guards were given attire that reinforced their roles. Prisoners wore a white smock garment embossed with their prisoner identification numbers, no undergarments, and a chain worn around their right ankle as a symbol of their status. Guards wore khaki uniforms and sunglasses and carried a whistle and a billy club to give them an air of authority and power.

Social influence in this study, which included specific social roles, obedience to authority, conformity, and ingroup-outgroup dynamics, was powerful and startling. In the words of Philip Zimbardo, the social psychologist who devised the study:

Our planned two-week investigation into the psychology of prison life had to be ended after only six days because of what the situation was doing to the college students who participated. In only a few days, our guards became sadistic and our prisoners became depressed and showed signs of extreme stress.

Philip Zimbardo on The Stanford Prison Experiment

At first, some of the prisoners resisted the authority of the guards, but over the course of just a few days, the guards cowed most of the prisoners by escalating the tactics they used for inducing a sense of powerlessness. For example, prisoners were woken up at 2:30 am by piercing whistles, and they were often required to do push-ups. As the prisoners resisted, the punishments became more extreme such as stripping rebellious prisoners and putting them into solitary confinement, and making prisoners clean out toilets with their bare hands. Even going to the bathroom became a privilege that the guards controlled.

As the guards consolidated their power, the resolve of the prisoners broke down. Four of the prisoners had emotional breakdowns within the first few days and some were allowed to leave the study. Some tried to become model prisoners to avoid the wrath of or gain favor with the guards. A common reaction was to become so enmeshed in the situation and the prisoner role that they lost their sense of individual identity, referring to themselves by their prisoner identification number, not their name.

After the study was discontinued, efforts were made by Zimbardo and colleagues to assess the participants’ psychological well-being and subjective experiences in the simulated prison. It was clear that the prisoners had experienced extreme emotional stress during the experiment. But extensive follow-up discussions and surveys over the next few years indicated that they had regained their emotional equilibrium and suffered no lasting trauma from the experience.

If you were a guard in this experiment, do you think that you would have gotten so far into the role that you would abuse your power? If you were a prisoner, do you think you would have been able to fight against a sense of powerlessness and despair? The social psychological perspective suggests that for most of us, the situation would be a stronger influence on our behavior than we believe.

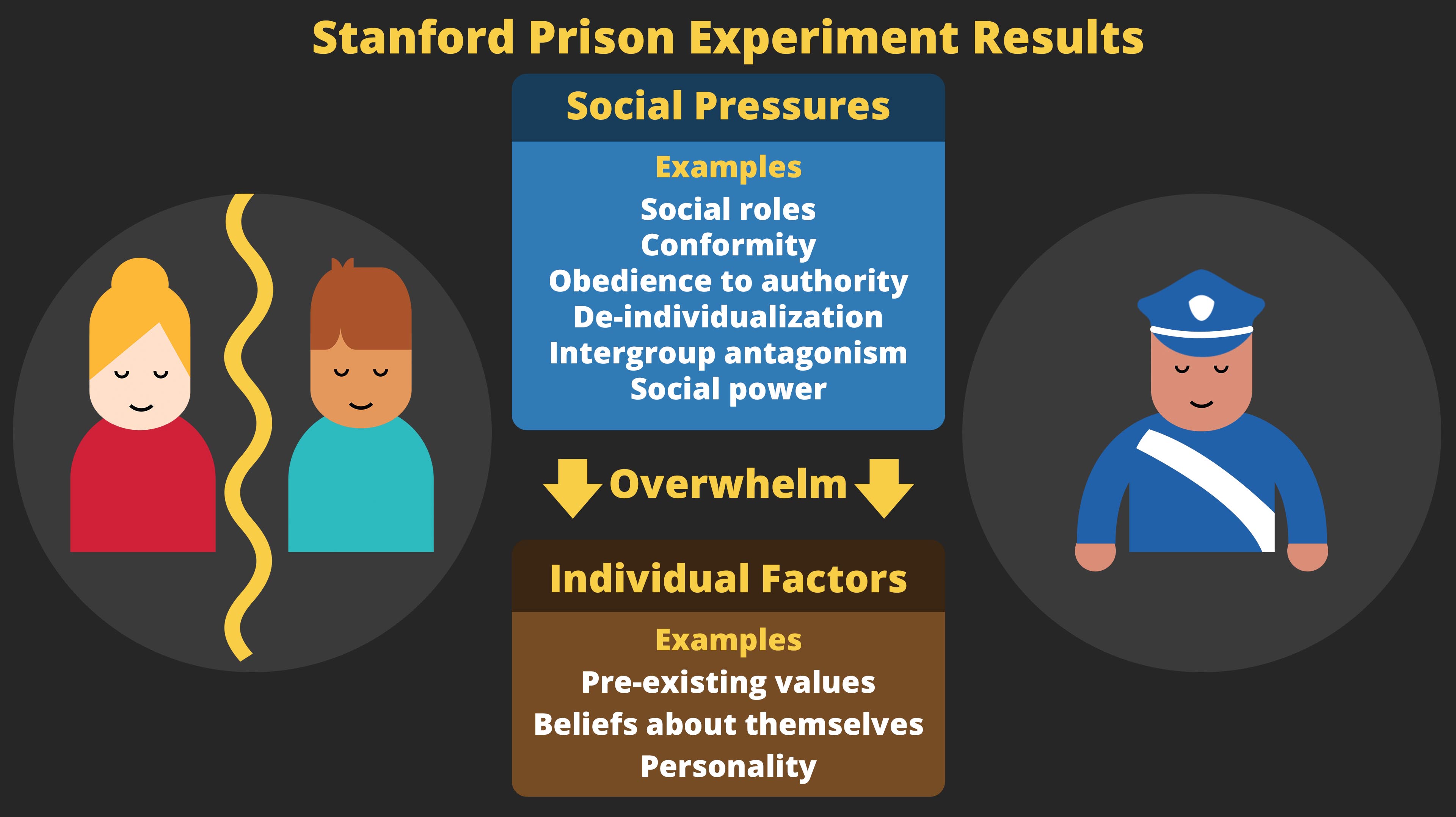

The Stanford prison simulation brought to bear a complex blend of social pressures and influences that overwhelmed individuals’ pre-existing values, beliefs about themselves, and personality. Results of the study showed that aspects of personality and other dispositional variables did not predict how people would react to their role or the situation. Instead, it was the power of social roles, conformity, obedience to authority, de-individualization, intergroup antagonism, and social power, among other social factors, that shaped the behaviors of guards and prisoners.

- Fundamental Attribution Error

- The scientific method

- Situational factors

- Testing human social behavior

- Bystander apathy

- Bystander Effect

- Kitty Genovese

- Darley and Latané Bystander Experiment

- Helping behavior

Section Focus Question:

What event precipitated the first experiments regarding bystander apathy, and how did Darley and Latané measure the reaction of their subjects?

Key Terms:

Principles of the Social Psychologist

Recognizing the power of social influence seems straightforward, but it is something we often overlook in our everyday life and sometimes resist. Instead, when we try to explain other people’s actions, we tend to focus more on person-based explanations and underestimate possible situational factors. This tendency is called the Fundamental Attribution Error and has been extensively documented in psychological research.

A second principle of social psychology approaches the study of human social behavior using the scientific method. Social psychologists use many kinds of research designs, but when possible they prefer to conduct experiments so that they can establish with greater precision what specific aspects of a social situation causes the outcome of interest. Such experiments of social situations are often complicated and challenging to arrange and complete, as humans can be quite perceptive and sensitive to being observed.

Bystander Intervention in Emergency Situations

Let us now return to the example of bystander apathy in the Introduction of this unit. The essential question was: How could so many people pass by a person in need without helping? Our first response may be that there must be something intrinsically wrong about the people — they are callous or uncaring. You should now realize that this may be an instance of what is called the Fundamental Attribution Error, where we focus on the person instead of the pressures of the social situation.

It could be true that the reason the bystanders did nothing reflected something about their values or character, but the social psychological perspective offers an alternative idea. Perhaps features of the social situation and social influence have more to do with bystander apathy than individual, person-based values, character, or personality tendencies. In fact, decades of research have demonstrated that there is a Bystander Effect, the phenomenon whereby the more witnesses there are during a potential emergency, the less likely that any one person will intervene to help. Each is assuming that the other will do something.

In a classic social psychological experiment in 1968, John M. Darley and Bibb Latané tested the hypothesis that the more bystanders there are during a potential emergency situation, the less likely it was that someone would intervene to help. Darley and Latané were motivated to understand information that was reported about the murder of a single woman, Kitty Genovese, near her apartment in New York in 1964. Newspapers reported that the attack on Genovese was prolonged, with several attacks happening during an approximately 30-minute time period. It was initially reported that as many as three dozen people heard her screams or witnessed part of the assault, but did not call the police until the last assault. Later research demonstrated that early reports exaggerated the number of witnesses, but people were still amazed that most bystanders did not intervene during the course of the attack.

Darley and Latané designed a study to evaluate whether the number of bystanders would cause or deter helping behavior. They recruited 72 female and male participants to take part in their study. When they arrived, participants were led to a small room with headphones and a microphone. The experimenter asked the participants to put on the headphones and listen for further instructions, then left the room, closing the door behind him. Via the headphones, the experimenter conveyed additional information about the study, stating that the participant would be engaging in an anonymous conversation with others about the pressures of living in an urban environment. To ensure a candid conversation, the experimenter said that he would not be listening in on the conversation. The conversation was set up so that each person would take a turn speaking for about two minutes, and during this time only the speaker could be heard. (All other microphones were deactivated.)

The results of the study provided strong support for the hypothesis that the more bystanders, the less likely any one person is going to help.

- Situational/social influence analysis

- Application of the scientific method

- Legacy of Darley and Latané

- Dillon and Bushman

- Digital bystanders

- Bystander Intervention Model

- Distraction

- Interpretation

- Diffusion of responsibility

- Appropriate skill-set

- Consequences

Section Focus Question:

What model has been devised to analyze bystander intervention, and how has it enriched the study of social psychology?

Key Terms:

Although seemingly counter-intuitive, the bystander effect has been demonstrated many times in other experimental and field studies. By applying a situational analysis, social psychologists have come to understand that the decision to help in a potential emergency is a function of many factors and social influences that may be at play in any given setting.

The work on the bystander effect is an instructive example of the approach used by social psychologists to understand human behavior. First, it applies a situational and social influence analysis to a phenomenon of interest. In doing so, social psychologists are able to arrive at insights into the dynamics of helping behavior beyond person-focused explanations. Second, it illustrates the scientific method as applied to the study of social behavior. By conducting carefully controlled experiments, along with other types of research designs, social psychologists were able to isolate specific variables within complex settings and systematically test whether they make a difference in helping behavior or not.

Furthermore, science is a cumulative endeavor. The Darley and Latané study was just the first of many studies that helped social psychologists establish the parameters under which people will or will not help. The principles established through empirical research can be extended to novel situations. Although the original bystander intervention work was conducted nearly 50 years ago, long before the internet, contemporary researchers are showing that it has relevance in the age of social media. For example, Kelly Dillon and Brad J. Bushman in a study in 2015 applied the Bystander Intervention Model to cyber bystanders or digital bystanders, people who witness distressing events in the virtual world. They found a similar effect, where the more digital bystanders there were, the less willing they were to report disturbing events in the virtual world.

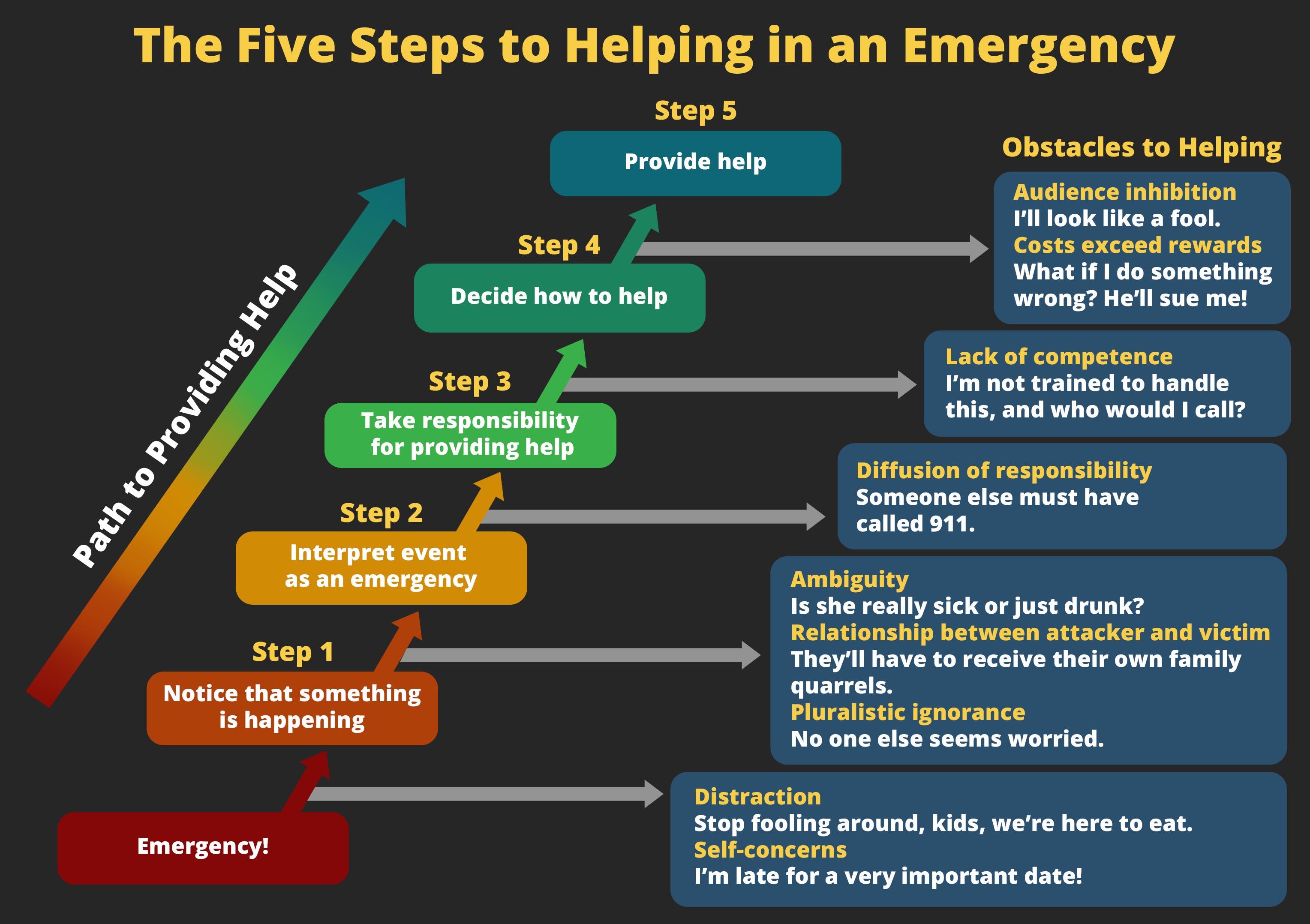

Based on their and others’ research, Darley and Latané (1970) developed the Bystander Intervention Model, a five-step model for understanding when people will or will not intervene in an emergency.

- One must notice that there is a potential emergency. Being in a hurry or distracted likely would lead to no help being given. Studies have shown that distracted bystanders fail to notice that a person may be in need of help.

- One must interpret the situation as an emergency. They found that, when a situation is unclear, the influence of others’ behaviors can have a large effect on our own choice to help or not. If others seem unconcerned, we are likely to assume that there is no emergency. However, the catch is that those around us may also be looking to others for guidance. The net effect can be pluralistic ignorance, wherein people assume the inaction of others implies that there is no emergency.

- One must assume responsibility for intervening. The original Darley and Latané study clearly demonstrated diffusion of responsibility. When others are around, we may assume that “someone” has done or will do something to address the situation, making it less likely for us to act.

- One must determine if she or he has the appropriate skills or knowledge to help. In many situations, bystanders may conclude they do not have the ability to assist, such as knowing how to render first aid or lacking the mobility and strength to help.

- One must weigh the consequences of helping and conclude that it is worth the risk to help. After all, there might be physical danger to oneself, or legal jeopardy, or embarrassment associated with helping, that might deter a bystander.