Conformity and Obedience

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

How does our psychological need for conformity and obedience influence our daily lives?

- Incidence of conformity

- Definition of conformity

- Social norms

- Reasons for conformity

- Asch experiment

- Information conformity

- Normative conformity

Section Focus Question:

What are the various social norms that cause us to want to conform?

Key Terms:

Would you be insulted if someone called you a conformist? For many Americans, the idea of being a conformist has negative connotations. Following the crowd is seen as undesirable. Instead, Americans tend to value independence, and uniqueness. However, the social-psychological perspective suggests that we may conform to the behaviors of other people more often than we realize, or wish to acknowledge.

Conformity

Conformity is when we bring our behavior or beliefs in line with others. Conformity can be very subtle; it can occur without anyone even trying to influence us. Sometimes others do not need to make an effort at all; they need only engage in some behavior for us to observe and imitate.

There are many examples of conformity in our everyday lives. For example, when you were younger, did you ever own, or know people who owned beyblades, fidget spinners, Livestrong wristbands, or a “Vote for Pedro” shirt? Were you into energy drinks, or addicted to Angry Birds for a time? These are all examples of fads. For a time, “everyone” seems to be intensely into some trend or fashion, but interest can fade quickly. Looking back, you may even be embarrassed by some of the fads in which you participated.

Another example of everyday conformity is when we follow social norms. Social norms are rules that a group has for dictating the acceptable values, beliefs, and behaviors of its members. Many norms are unspoken, having been learned at an early age and so deeply integrated into our daily interactions that we are unaware we are following them until someone violates those unspoken rules.

For example, strangers in an elevator stand facing toward the door and tend to stay in their own “bubble,” not speaking to or looking at others. What do you think would happen if someone decided to face the back and stare at the other passengers? Or suppose when striking up a conversation with you, a person stands just inches from you instead of giving you your “personal space.” How would you feel and react? Knowing and conforming to social norms allows for smooth interactions and may help people to avoid misunderstandings.

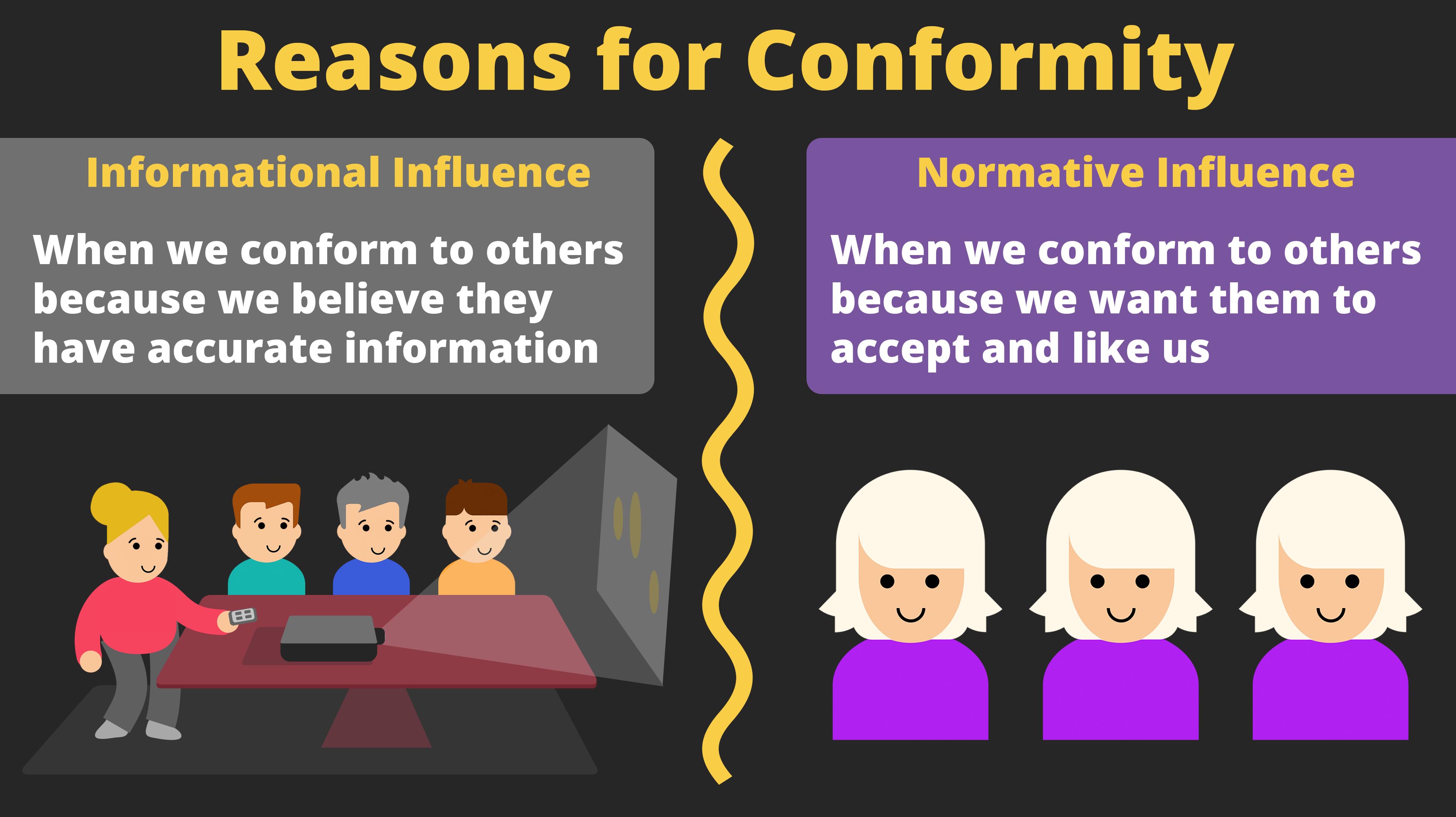

Reasons for Conformity

There are two major reasons why people conform to the behaviors and expectations — real or perceived — of other people. One reason we conform is because we want to fit in with those around us. Normative influence occurs when we conform to others’ beliefs or behaviors because we want to be liked and accepted by the people around us. Alternatively, we may be strongly motivated to avoid rejection by the group. It follows that normative influence is at its strongest when we are with people whose opinion matters to us.

A second reason we conform is that we believe that others are doing the right thing. Informational influence is most likely to occur in situations where we are uncertain about how to act. In these situations, we look to others and conform because we believe that others’ interpretation of an ambiguous situation is more accurate than ours. Emergency situations are times when informational influence may be especially powerful. Most people are not trained to deal with emergencies, so when confronted with an unexpected and possibly dangerous situation, we look to see how others are reacting. Another example is when we enter a situation we have never encountered before and are uncertain about the “rules,” such as a first-generation college student setting foot on a college campus for the first time, or visiting a foreign country.

A good example of Normative Conformity is the Asch experiment discussed in Unit 1 on Psychological Science. You may remember that Solomon Asch created a paradigm or a standard experimental procedure for studying group conformity. In his study, participants were placed in a group with several other participants (who were actually confederates of the experimenter) and asked to make simple judgements about the lengths of lines on a piece of paper. The experimenter then went around the room asking the confederates for their judgments, and they gave intentionally wrong answers. The actual participant, who gave the right answer in a previous round, changed his or her answer to conform with the confederates.

This is a powerful example of normative influence on behavior. In this situation, conformity was likely not due to informational influence because people knew what the right answer was. In one variation of the experiment, participants were allowed to give their answer anonymously and without group pressure, and they were very accurate in their estimates. Rather, the need to be accepted by others, to not be the fool, proved to be a powerful motivation for public compliance.

Numerous replications of Asch’s study have been performed since the 1950s. In one meta-analysis in 1996, Rod Bond and Peter B. Smith examined results from 133 conformity studies. One major conclusion they came to was that levels of conformity in Asch-type experiments have declined in America since the 1950s. A second conclusion was that cultural values impacted rates of conformity, with rates being higher in collectivistic and interdependent cultures. These are cultures in which cultivating social harmony and fitting into the group are more highly valued than standing out as a unique individual.

Obedience

- Holocaust

- Milgram experiment

- Teachers in obedience study

- Experimenter in obedience study

- Milgram experiment results

Section Focus Question:

How powerful is our psychological desire to be obedient?

Key Terms:

During the Holocaust of WWII, millions of Jews were murdered in Germany under the Nazi regime. When the extent of this genocide became known outside of Germany, people around the world were appalled and horrified by the inhumane cruelty. Some German citizens were actively involved in the systematic genocide. Others passively allowed it to occur. How could this have happened?

The horrors of the Holocaust motivated many social scientists to study the social phenomena that would have allowed this to happen. The Holocaust partly motivated Asch’s experiments in conformity. Others wanted to investigate what other factors were strong enough to compel average, everyday people to violate their deeply held values and cause tremendous pain to a person who had done them no harm. In a series of provocative studies conducted in the 1960s, social psychologist Stanley Milgram showed that the human drive toward obedience could be an important factor in overcoming moral beliefs.

Milgram’s Obedience Studies

Obedience is a change in one’s behavior that is ordered by another person or group. It differs from conformity. With conformity, no one has to compel explicitly a person to change their behaviors. With obedience, someone is directly telling people what to do.

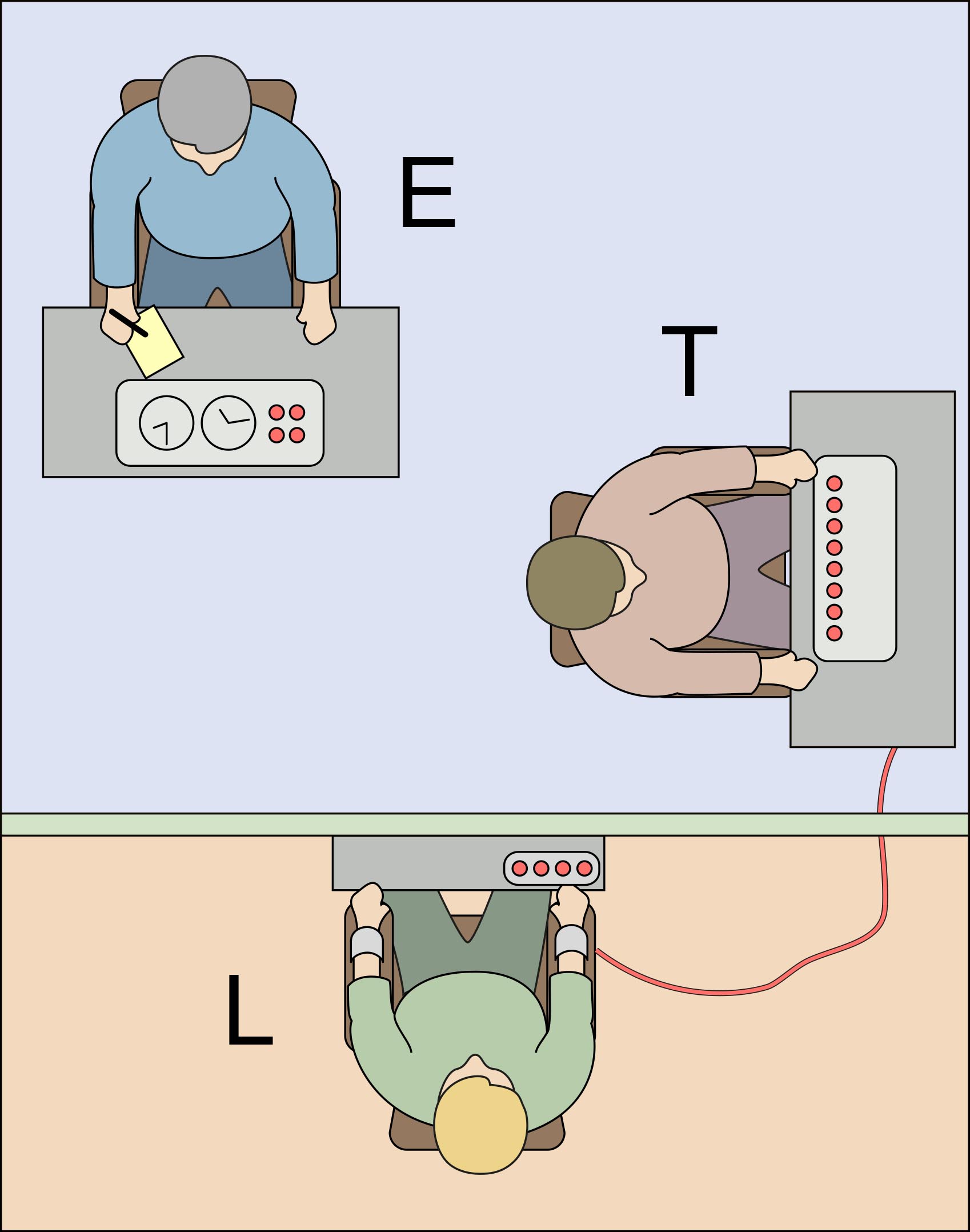

Milgram created an experimental situation in which participants encountered two contradictory pressures: (1) the urge to obey an authority figure and (2) the desire to stop causing pain to a stranger. Participants in his studies – recruited from New Haven, Connecticut, and representing a broad range of demographic backgrounds – came to his Yale University laboratory believing that they had volunteered to take part in a study about learning and memory. Once they arrived, they were told that the study was to determine whether experiencing punishment could improve memory performance. The participant was always assigned the role of Teacher, and a second “participant” – who was really a confederate of the experiment – was always assigned the role of Learner. The Learner’s job was to memorize a list of word pairs. The Teacher’s job was to read the word pairs and test the Learner’s memory of those pairs. If the Learner made a mistake, the Teacher was to administer an electrical shock to the Learner. With each mistake, the voltage of the shock was increased. The role of the Experimenter — played by an actor in a white coat and also a confederate of Milgram — was to ensure that the experimental procedures were followed.

The Milgram experiment was actually a series of 19 variations of the standard procedure described above. The most well-known variation was the Voice Feedback condition. In this condition, the Learner and Teacher were taken to a small room apart from the main lab. The Learner sat in a chair, had his arms strapped down, and had electrodes attached to his arm, supposedly the means by which he would receive the electrical shocks. As the Teacher observed this procedure, the Learner informed the Experimenter that he had heart problems and asked if the shocks were dangerous. The Experimenter assured him: “Although the shocks may be painful, they are not dangerous.” After this, the Teacher and Experimenter closed the door and returned to the main lab. In this condition, although the Learner was in a different room than the Teacher, he was able to verbally communicate with the Teacher via an intercom.

The Experimenter then introduced the Teacher to his task. The Teacher was seated before a large shock generator machine with a row of switches labeled with a voltage and a verbal description. The intensity of the voltage increased by 15 volts with each switch, with the first switch on the left labeled 15 volts (slight shock). The switches on the far right were labeled 315 volts (extreme intensity shock), 375 volts (danger: severe shock), and finally 435 volts and 450 volts were simply labeled XXX. The Teacher first read a series of word pairs that the Learner was to memorize (e.g., blue-box). Then, the Teacher repeated the list but only read one word of the pair followed by four possible answers (e.g., blue: sky, ink, box, lamp). The Learner then tried to identify the correct pair from the list (e.g., box). If the Learner made a mistake, the Teacher was to administer a shock via the shock generator. With each mistake, the shock administered by the Teacher was to increase in intensity by 15 volts. The Teacher was given a 45-volt shock (between slight and moderate) to provide some reference as to how painful the shocks may become.

Unbeknownst to the Teacher, the Learner actually received no shocks. Instead, as soon as the Teacher and Experimenter left, the Learner freed himself from the straps and electrodes and set up a machine that gave pre-recorded responses to the Teacher’s inquiries throughout the experiment.

However, from the Teacher’s point of view, he was administering painful punishments. As the test went along, the script called for the Learner to make a series of mistakes and to receive shocks from the Teacher. At 75-, 90-, and 105-volts, the Teacher heard the Learner grunt as if in pain. At 120 volts, the Learner shouted that the shocks were becoming painful. At 150 volts, the Learner begged to be let out of the experiment: “Experimenter, get me out of here! I won’t be in the experiment any more! I refuse to go on!” This type of refusal to continue and cries of pain continued until 300 volts, after which nothing more is heard from the Learner.

The Teachers experienced concern and anguish as the Learner cried out in pain, but they were met with the commands from the Experimenter that they must continue with the experiment. The Teachers would often hesitate about going on. As the shock levels escalated, they often pled with the Experimenter to check on the health and well-being of the Learner. They often pronounced that they would not go on. In response to these moments of defiance, the Experimenter gave pre-scripted responses: “Please continue;” “The experiment requires that you continue;” “It is absolutely essential that you continue”; and “You have no other choice; you must go on.” These verbal responses were the only form of coercion in the experiment.

Imagine being the Teacher in this study. How far do you think you would go on the shock machine? What percentage of participants in the actual study do you think went all the way to 450 volts? Before publishing his results, Milgram described his experimental procedure to a number of psychiatrists and asked them to estimate how many people out of a hundred they thought would go to the end of the shock machine. The consensus was that only one out of 1,000 (0.1 percent) would do so. Their assumption was that only those with sadistic tendencies would inflict that much pain on another person.

In fact, Milgram found that 63 percent of participants in the Voice Feedback condition went all the way to 450 volts. The psychiatrists at the time underestimated the power of social influence. In imagining ourselves as the Teacher, most of us believe that we would be the one to break off and disobey the Experimenter. However, in thinking about this, we too may be underestimating just how susceptible we ourselves are to social influence.

- Fatal results in Milgram experiment

- Ethical guidelines

- Participants’ distress in obedience study

- Willingness of participants to obey to a fatal result

- Character of the situation matters most

- Proximity of Learner

- Proximity of the Experimenter

- Other observers to the experiment

Section Focus Question:

Under what conditions are we most likely to be obedient?

Key Terms:

Several aspects of the social setting were identified as crucial to determining whether people obeyed or disobeyed.

- The proximity of the victim and the Teacher. The more removed the victim, the further Teachers went in their punishments.

- The proximity of the authority figure giving the orders. In this case, the more removed the Experimenter, the less the Teachers would escalate in their punishments.

- The presence of additional people in the situation. Introducing other people into the situation served dramatically to increase or decrease obedience by the true participants. When the additional “participants” (actually trained confederates of Milgram), went along with the Experimenter’s orders, the real participant was more likely to obey. In contrast, participants were likely to defy the Experimenter if only a few other “participants” chose to rebel against causing harm.

Milgram’s approach to the study of obedience is a classic example of the social psychological perspective, as illustrated in his final conclusions:

It would be a mistake to believe that any single temperamental quality is associated with disobedience, or to make the simple-minded statement that kindly and good persons disobey while those who are cruel do not… . Moreover, the disposition a person brings to the experiment is probably less important a cause of his behaviors than most readers assume.

For the social psychology of this century reveals a major lesson: Often, it is not so much the kind of person a man is as the kind of situation in which he finds himself that determines how he will act.

Stanley Milgram Summerizes Experiment