Stereotyping, Prejudice, and Discrimination

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

What are three theories that seem to explain prejudice and what do they say?

- Multiple causes of prejudice

- Ingroup

- Outgroup

- Reactions in intergroup dynamics

- Influences on ingroup relations

- Stereotypes

- Prejudice

- Discrimination

Section Focus Question:

What is the dynamic of ingroup and outgroup dynamics and what does it mean to stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination?

Key Terms:

The study of stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination has long been a central research agenda in social psychology. The 1954 publication of Gordon Allport’s classic book, The Nature of Prejudice, summarized research on prejudice up to that point in time, and in many ways set the agenda for the next 60-plus years of social psychological research in this area. Allport recognized that prejudice was a complex and multifaceted phenomenon with many possible antecedents (causes). As he stated:

We may lay it down as a general law applying to all social phenomenon that multiple causation is invariably at work and nowhere is the law more clearly applicable than to prejudice.

Gordon Allport on Prejudice

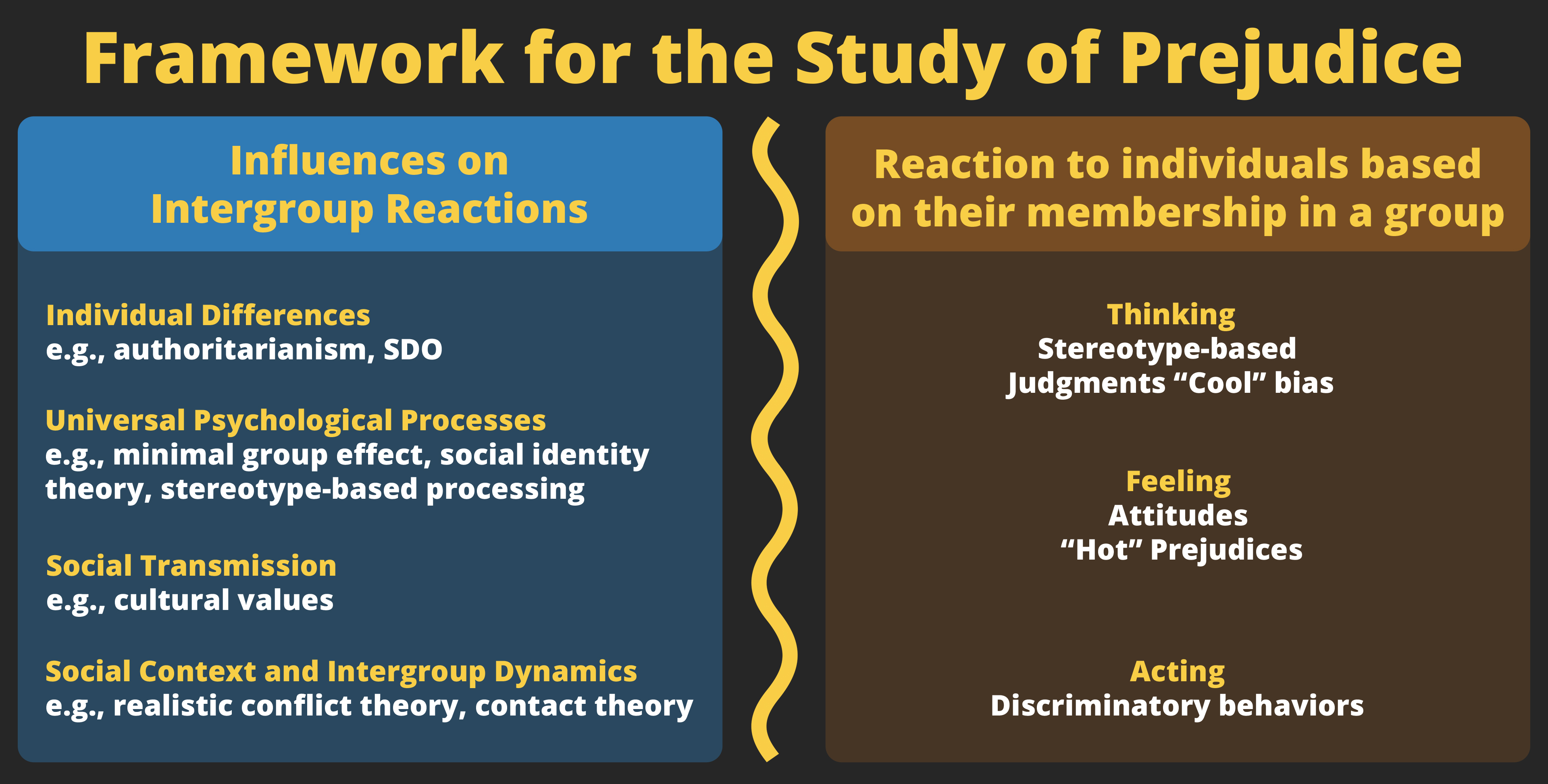

Not only are the potential causes of intergroup antagonism varied and complex, the outcomes and expressions of that antagonism are also varied and complex. In this chapter we will outline a general framework for understanding key factors at play that can affect intergroup dynamics.

Framework for Studying Intergroup Relations

The terms ingroup and outgroup are key concepts in the study of intergroup relations. Outgroup is a general term used to describe people who we perceive as different from ourselves in some important way. Conversely, ingroup refers to people with whom we feel a shared identity. Perceptions of ingroups and outgroups vary with context and other factors, such as what makes you feel distinct or unique in a situation. For example, when visiting another state, a person may think of him or herself in terms of a home state (e.g., “I’m a Californian”); but when visiting a foreign country he or she may think in terms of her nationality (e.g., “I’m an American”). However, some identities are so salient and often used that they easily become activated and are then used to perceive and react to those around us.

The table below illustrates core factors in the study of intergroup relations based on the work of Duckitt (1992). This figure is a simplified version of how these factors interact with one another (e.g., stereotypes can influence how we feel and act towards others), but it serves as a useful organizational framework.

On the right side of the diagram are various ways in which we may react to people whom we perceive as members of an outgroup. These include our thoughts and judgements, our emotional reactions, and how we behave toward a person or group. Stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination can occur when people are treated in a certain way based on their membership in a group, and not due to their own individual, unique characters and their own merits. Each of these terms has colloquial, everyday meanings and people often use them interchangeably. Social psychologists mean specific things when they use each term, so let’s go over the definitions.

Stereotypes are a set of beliefs about the personal attributes associated with a particular group of people. In the essay Is Stereotype-based Bias Inevitable?, you learned about the concept of categories and schemas, which are ways in which we organize our knowledge of the world. Stereotypes are a kind of schema organized around our beliefs about groups of people. For example, a common stereotype of elderly people is that they are slow, forgetful, and physically weak. On the one hand, like any schema, stereotypes can offer cognitive efficiency as they provide a simple, thumbnail sketch of what a particular group may be like. On the other hand, stereotypes can prove to be inaccurate in and of themselves, as well as when applied to specific individuals.

Prejudice is a negative evaluation about a group. Emotional reactions to a group may range from mild dislike to more intense reactions such as disdain, hostility, or disgust, and these in turn may be applied to individuals we believe are part of that group. In studying intergroup relations, social scientists tend to focus on negative emotional reactions; however, it is also possible to associate positive feelings with a group, particularly with one’s ingroup (i.e., ingroup favoritism).

Discrimination consists of negative actions toward a person because of his or her membership in a particular social group. Discrimination can occur at many levels. At the interpersonal level, you may refuse to help someone or allow your children to play with someone because of that person’s group membership. At an institutional level, members of a group may not be hired or promoted because of their group membership.

Factors that Influence Stereotyping, Prejudice, and Discrimination

- Complementary aspects of stereotype bias

- Authoritarian personality

- Minimal group effect

- Tajfel’s experiment

- Social Identity Theory (SIT)

- Tolerance and growing up

- Protestant Ethic value system

- Humanitarian-egalitarian value system

Section Focus Question:

What is minimal group effect and how does it or does it not explain prejudice?

Key Terms:

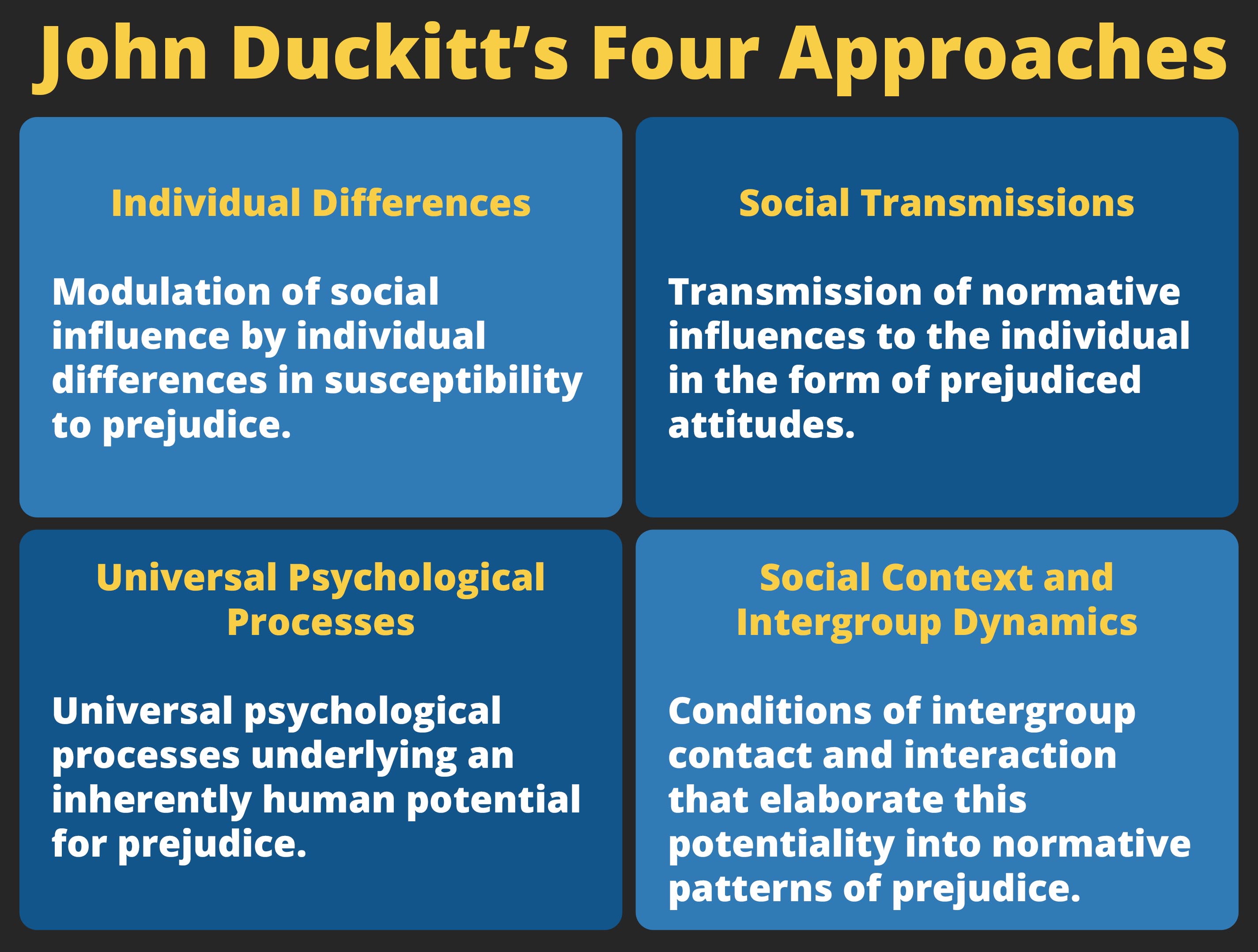

There are many factors that influence how we react to outgroups. In his 1992 review of the literature, John Duckitt suggested that many of the theories on prejudice proposed throughout the years can be subsumed under four general approaches — Individual Differences, Universal Psychological Processes, Social Transmissions, and Social Context and Intergroup Dynamics. Duckitt asserted that each of these approaches should be seen as complementary rather than competitive explanations.

Individual Differences

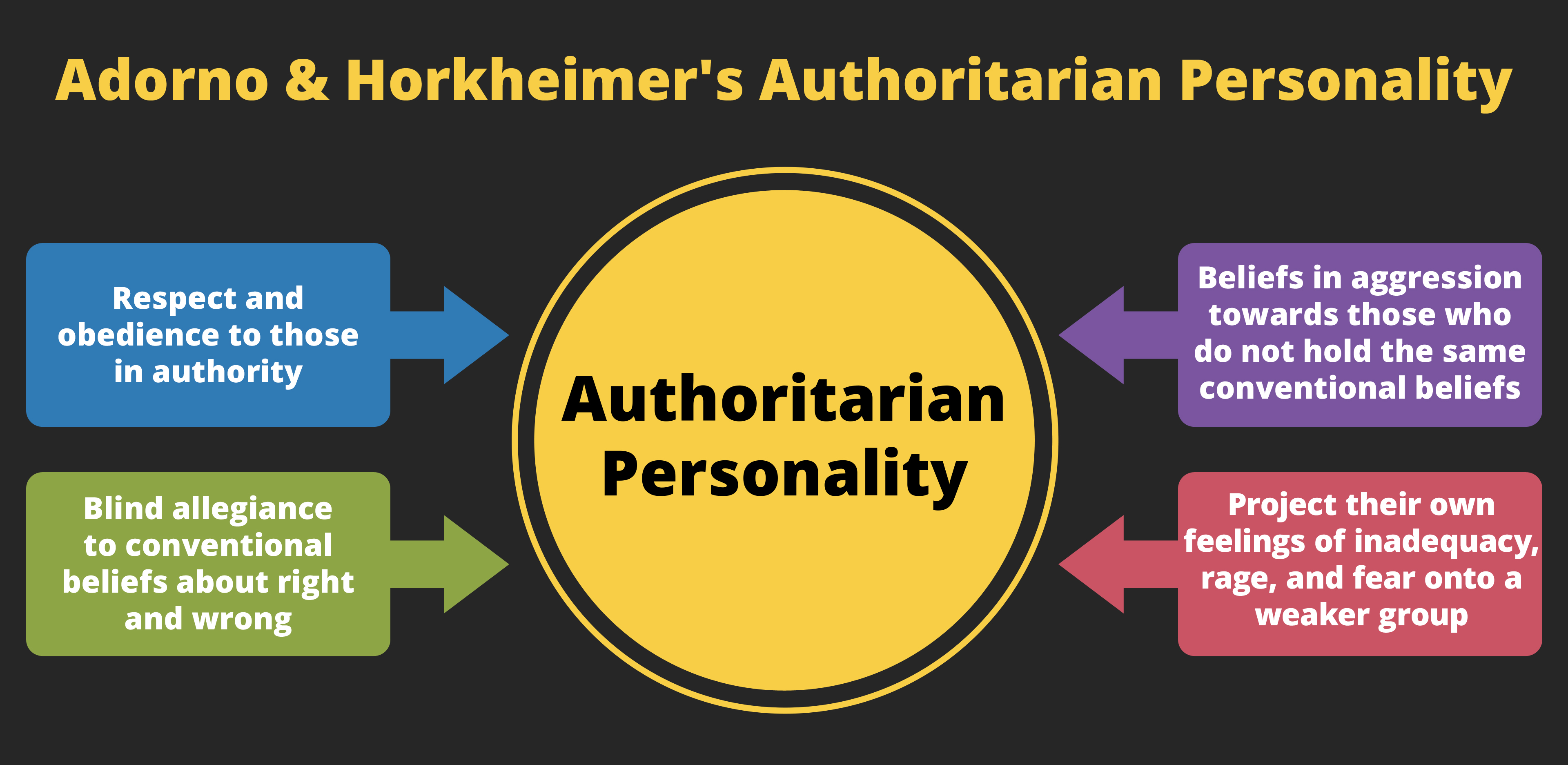

Some approaches focus on aspects of individuals — their personality, dispositions, or ideological beliefs, among others — that may predispose them to tolerance or intolerance of outgroups. This approach is personified by the work of Theodore W. Adorno, et al., The Authoritarian Personality (1950). This book has been highly influential in inspiring research and understanding of the psychological dynamic of authoritarians. These are people who are predisposed to being obedient to authority figures, adhering to traditional values and beliefs, and having the willingness to aggress against outgroups whom an authority figure deems a threat. Research over the last 60 years has consistently shown that those with authoritarian tendencies are intolerant toward a broad range of outgroups.

Universal Psychological Processes

Another approach to understanding prejudice is the notion that prejudice and discrimination are by-products of the way that humans process information. One example of this approach is the minimal group effect. It turns out that simply perceiving some people as “us” and others as “them” can set the stage for ingroup favoritism.

It would be difficult to determine if this were a basic psychological process if we tried to study real-world groups with a history of antagonism because so many factors may have worked to create the hostility other than an “us vs. them” mentality. Instead, by creating an experimental situation in which the ingroup and outgroup divisions were based on an arbitrary quality that had no meaning to participants until they went through the study, in 1971 Henri Tajfel, et al., were able to show that the minimal group effect may be the byproduct of basic psychological processes.

In one version of these studies, participants were first shown a series of abstract paintings by painters Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky, and asked to provide their reactions to them. They were then told that some people preferred Klee but others preferred Kandinsky, and based on their responses they were instructed as to which group they belonged. In reality, the groups were randomly assigned. They were then given some money and told that they were to allocate it to the other study participants, dividing it however they liked. The only thing they knew about the other participants was their supposed painter preference — Klee or Kandinsky. Participants demonstrated ingroup favoritism by giving more money to people they thought were part of their ingroup. Although this could be interpreted as discriminating against the outgroup, based on subsequent studies, Tajfel suggested that the minimal group effect is more about favoring the ingroup than discriminating against the outgroup.

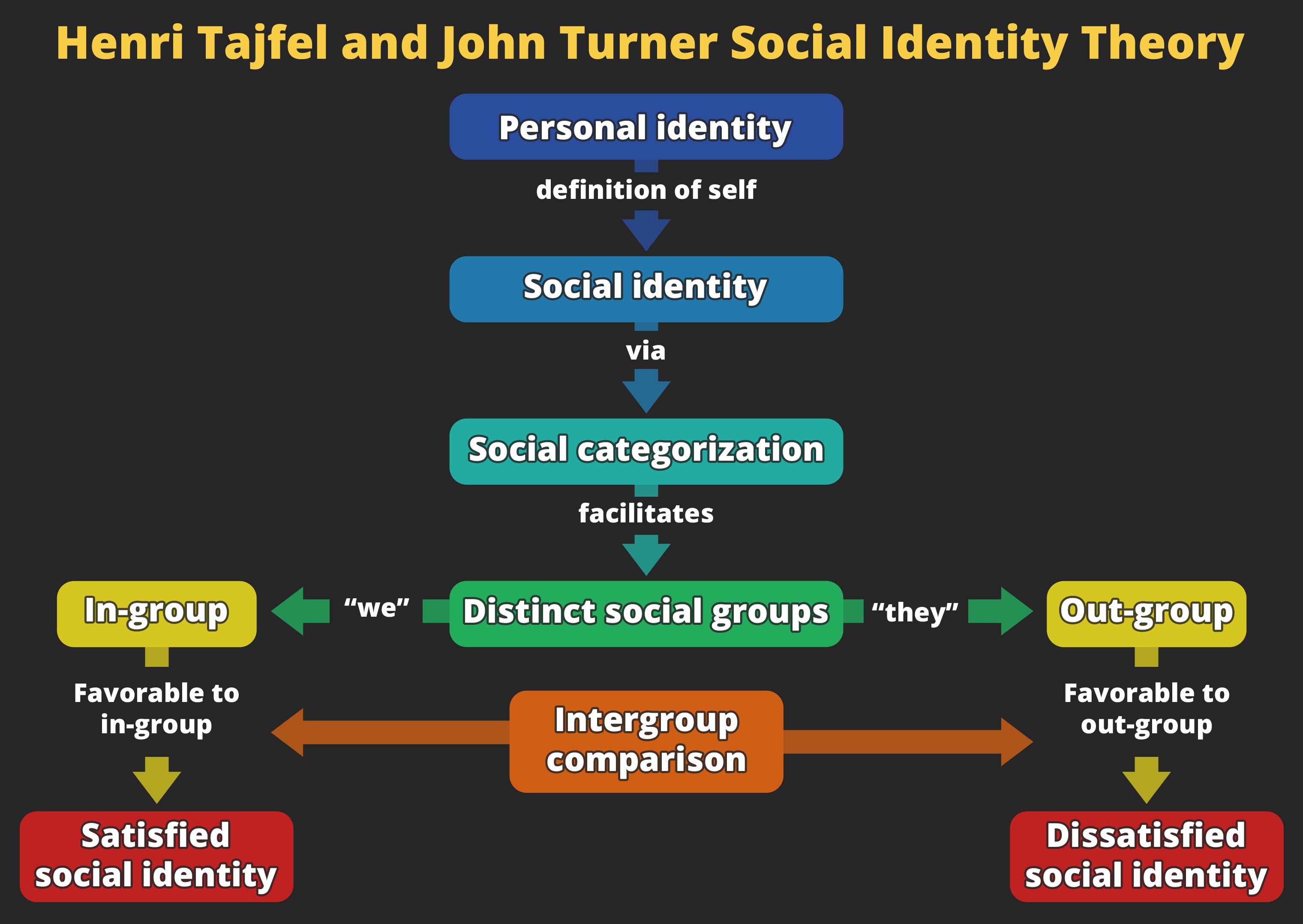

The minimal group effect is part of a larger theory of prejudice developed by Henri Tajfel and John Turner (1986) known as Social Identity Theory (SIT). According to SIT, people are motivated to see themselves in a positive light, and they use various strategies to do so. One way we can derive self-esteem is through the social groups - or social identities - to which we belong (e.g., gender, race or ethnicity, religion, politics). When one’s group is successful, such as winning a contest, we feel elevated. Based on this perspective, people should be motivated to engage in ingroup favoritism because it elevates one’s ingroup relative to an outgroup.

A second possibility is that people will be motivated to engage in outgroup derogation, which is negatively evaluating outgroups. Research since SIT’s inception has generally supported that ingroup favoritism occurs due to social identity processes, but there is less support for outgroup derogation. Another process that can lead to biased judgments and discrimination is through the stereotypes we hold about a group. The Is Stereotype-based Bias Inevitable? essay in this unit details some of the ways that this occurs.

Social Transmissions

One long-term influence on whether individuals adopt more or less tolerant attitudes toward outgroups are the social norms and values that are instilled in them as they grow up. A broad influence is cultural values. For example, in the US two core values systems are the Protestant Ethic, which emphasizes the importance of hard work, self-discipline, and individual achievement, and humanitarianism-egalitarianism, which emphasizes the importance of concern for others, equality for all, and social justice. Adhering to humanitarian-egalitarian values has consistently been related to more favorable attitudes toward outgroups. Other modes of social transmission are more immediate than broad cultural values, such as parental and peer influence.

Social Context and Intergroup Dynamics

- Realistic Conflict Theory

- Robbers Cave experiment

- Intergroup Contact Theory

- Jigsaw classroom

- Jigsaw classroom advantages

Section Focus Question:

What are ways psychologists have found to induce and solve negative intergroup relations?

Key Terms:

Groups interact within a social context, and the circumstances of that context can serve to heighten or lessen intergroup tensions. One example of this approach is Realistic Conflict Theory, which states that competition over limited resources (e.g., jobs) can create or exacerbate intergroup tensions, resulting in increased prejudice and discrimination.

A classic test of Realistic Conflict Theory was conducted by Muzafir Sherif, et. al. (1961). Using a summer camp in Robbers Cave State Park, Oklahoma, Sherif systematically varied aspects of the social context as a means for creating and reducing intergroup hostility between two groups of 11- to 12-year-old boys. Following a rigorous procedure, about 20 boys — whom they deemed as psychologically and socially well-adjusted and who shared similar white, Protestant, middle-class backgrounds — were invited to take part in a summer camp experience. None of the boys had met previously and none were aware that they were part of an experiment in intergroup relations.

In the first phase of the study, the boys were randomly assigned to one of two groups. Starting from when they were picked up by bus and transported to the camp, the two groups were kept separated and were minimally aware of the other’s existence. During the first few days of camp, the boys were encouraged to bond with those in their group. Distinct ingroup identities and social structures developed. One group began calling itself “the Rattlers” and the other “the Eagles.” Within the groups, boys took on certain roles, found a place in the social hierarchy, and were sometimes given nicknames. An esprit de corps and cohesive identity developed within each group.

In the second phase of the study, the groups of boys were brought together in an atmosphere of competition for valued but limited resources. A tournament of contests was arranged — baseball, touch football, tug of war, and so forth — with individual prizes and an overall trophy to be awarded to the winning team. At first, the boys displayed good sportsmanship, but as the contests went on this devolved into name-calling, insults, scuffles, and cabin raids. In a controlled setting, Sherif and colleagues were able to create both strong ingroup identities and intergroup hostility among boys who only a few days before were strangers.

Having identified factors in the social context that enhanced intergroup hostility, Sherif and colleagues then sought to create good feelings between the rival groups. First, they had the groups participate in pleasant activities in the absence of any competition, such as watching a movie together. However, even in neutral situations, the animosity continued. This demonstrated that simply bringing together rival groups was not sufficient to reduce intergroup hostility and prejudice. Instead, these situations were used as opportunities to express their distaste for one another.

In the final phase of the study, Sherif and colleagues created conditions within the social context that eventually resulted in the Eagles and Rattlers becoming quite friendly with one another. The experimenters created a series of urgent situations whose solutions required both groups to work together for the common good. For example, the water supply of the camp was threatened because the pipe from the water tank broke. There was over a mile of pipe to inspect, and members from both groups worked side-by-side without negative incidents until the problem was solved. Similarly, the camp food truck “broke down” some distance from camp, and the only way to get the food to camp was by having everyone use the tug-of-war rope to pull the truck until it was able to start.

The situations Sherif created were based on Intergroup Contact Theory, which specifies the optimal conditions for reducing intergroup hostilities. These optimal conditions include:

- The two groups should be pursuing a common goal.

- The groups are interdependent, meaning that no one group can achieve the goal, instead the groups need to cooperate in order to reach that goal.

- The group should have equal status.

- There is institutional support (e.g., authority figures, norms) for reducing intergroup hostility.

The urgent situations encountered by the Eagles and Rattlers contained many of these conditions. The groups experienced common threats whose solutions required intergroup cooperation. The Eagles and Rattlers were of equal status because no one group had more power or resources than the other. The hostilities did not dissipate right away, but with each success, the groups became closer and antagonism died down. By the end of the camp, friendships had formed among the former rivals, and they voted to go home together in one bus.

Intergroup Contact Theory has been extensively tested since Sherif’s initial studies. Thomas F. Pettigrew and Linda Tropp (2006) conducted a meta-analysis of 515 studies of contact theory and concluded that careful implementation of the contact theory’s optimal conditions can be an effective means for reducing intergroup tensions. These studies covered a broad range of group types, including those based on race, ethnicity, religion, age, sexual orientation, and physical disability, among others. Their analysis found that optimal intergroup contact can be effective across a broad range of groups and contexts.

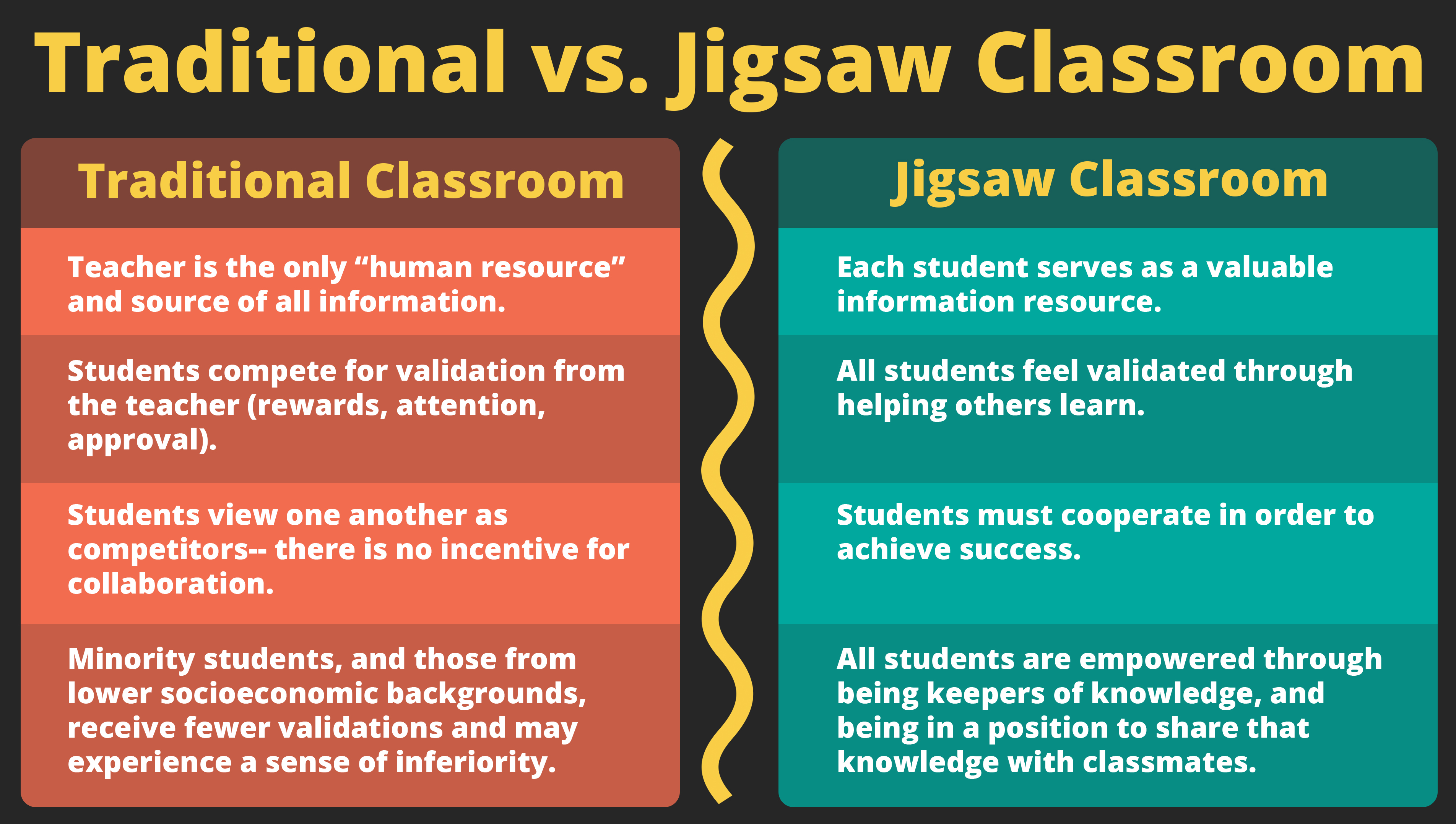

The Jigsaw Classroom

One powerful application of contact theory is the jigsaw classroom. This cooperative learning technique was developed by Elliot Aronson, et al., in the early 1970s to address problems following the desegregation of schools in Austin, Texas. Simply placing African American, Hispanic, and White students in the same classes for the first time produced a hostile atmosphere among groups of students who formerly had little contact with one another.

Guided by the principles of optimal intergroup contact, Aronson developed the jigsaw classroom technique as a means for reducing prejudice and increasing academic achievement. First, students were divided into small groups (typically five or six) which are diverse in terms of key characteristics (e.g., ability, gender, race, or ethnicity). Students were assigned specific roles (e.g., leader) and were then presented with the day’s lesson. The lesson was divided into 5 to 6 segments and each student was assigned responsibility for one of the segments. Students were only allowed resources for their specific segment. They were given time to learn about their segment and allowed to form “expert groups” by meeting with students from other groups who were assigned the same segment. Students then returned to their own groups and presented their segment to the other group members. They were then given a quiz on the material.

Decades of research have shown that the jigsaw classroom, wherever it is applied, is successful in reducing prejudice and stereotyping. In addition, the jigsaw classroom has been associated with increased self-esteem among students, enhanced performance in the classroom, and a greater likelihood that students socialize with those different from themselves.

One positive outcome of the jigsaw classroom experiments is that a clear understanding of the principles of social psychology not only informs us about human psychological tendencies in social situations and groups. It also tells us ways to repair rifts in our society that can lead to group conflict and even violence.