Indigenous Cultures

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

What were the natures of the Native peoples of the Americas, and what was the impact of Europeans on those societies?

- Aztecs

- Mayans

- Incas

- Density of Native population

- Bering Strait migration

- Calorie-rich foods

- Natives' lack of technology

- Mayan achievements

- Native conquest

- Hernán Cortés

- Maize (corn)

- Potatoes

- Mayan calendar

Section Focus Question:

How did the prehistoric populating of the Americas occur, and what were some of the characteristics of ancient civilizations in the Americas?

Key Terms:

In 1492 the Americas were home to a considerable variety of Native tribes, nations, and empires. The total population probably equaled that of continental Europe though estimates have varied wildly in the absence of concrete evidence. The unpeopled lands of the western hemisphere were first colonized between 15,000 and 40,000 years ago.

Archaeological and biological evidence indicate that they were descendants of Asians who crossed over to the Americas via the Bering Strait. Today this is open ocean but in those centuries a series of ice bridges during several ice ages permitted the migration of successive waves of people and animals. With the end of the last ice age about 15,000 years ago, the migration stopped. Thus, the people of the Old World and the New World became separated for 15 millennia (15,000 years) until Europeans began to cross the Atlantic starting in 1492.

The peoples of the pre-Columbian Americas, however, continued their migration, reaching the tip of South America about 11,000 years ago. At first, they hunted the large game, such as wooly mammoths until many of these species became extinct. About 9,000 years ago, at about the same time as in the Near East, agriculture was developed in Central Mexico and in the Andes, most particularly with the staple crops of maize (corn) and potatoes.

Cultivation practices spread and many Native groups moved from reliance on hunting and gathering to become large, settled populations and even cities. The Spaniards noted vast differences in these settled people. In the first 30 years until 1520, they observed small towns and chiefdoms of the Arawak, Taino, and Caribs in the Caribbean. In the next 30 years they were introduced to the large cities, sophisticated societies and empires of the Mexicans, the Incans, and the Mayans. As they explored the Gulf Coast, Southwest, and Great Plains of North America, they came across many people who were simple, nomadic hunters and gatherers.

The Native groups Europeans encountered may have presented themselves as occupying lands since perpetuity. But in fact they had conquered, colonized, and driven each other across the landscape for thousands of years. Changes in climate and Native-on-Native violence were the usual causes for the rise and fall of indigenous civilizations and migrations of weaker groups. But after the year 1000, increasingly there was another factor challenging the first Americans — a population decline that predated the arrival of Europeans and precipitated a more dramatic and irreversible population decline in many regions.

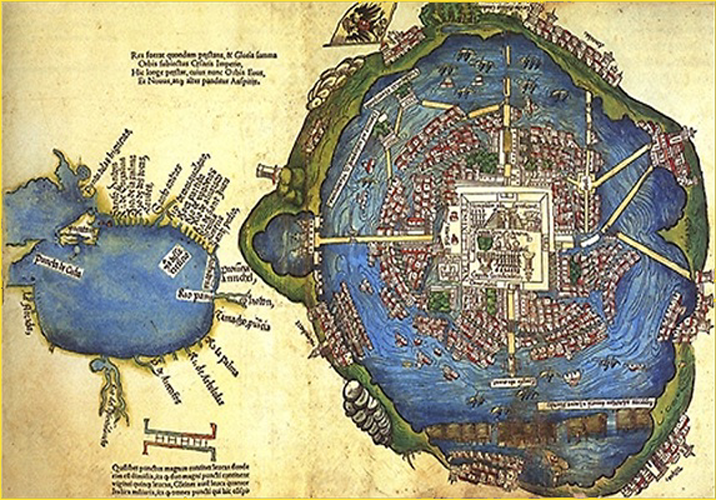

The most densely populated region was Central Mexico. Their sophisticated farming practices sustained approximately 20 million people. The Andean civilizations supported about 11 million with an intricate system of terrace farming, irrigation, roads, and trade at elevations above 5,000 feet. The Aztec capital Tenochtitlán, nucleus of the last major indigenous civilization of Central Mexico, was larger than almost all of the major cities of Europe. Tenochtitlan had a population density similar to many Chinese cities of the time. Cortés was so impressed with the wonders of this American city that he had a detailed map published in 1524, four years after executing the Mexican ruler Motecuhzoma, to illustrate the glories of the civilization he had conquered and largely destroyed.

Some indigenous people of the Americas had formed knowledgeable and sophisticated societies. They had writing systems, developed effective medicines from indigenous plants, built elaborate aqueducts and terraces for farming, and elaborated their own astronomy — famously in the case of the calendar developed by the Mayans on the Yucatan Peninsula. Mexicans, Mayans, and Incans had large cohorts of priests and complex religions using both natural and anthropomorphic gods and built pyramids of worship.

They had elaborate political systems and economic structures that sustained empires and facilitated long-distance transport and trade. Geographically, the Incan Empire occupied more territory than any European empire at this time, while the Mexicans created a society whose vibrant intensity included ordinary pleasures that Europeans quickly adopted and modified, such as chocolate seasoned with chili.

Despite their sophistication, the indigenous people of the Americas did not know large scale metallurgy and machines, gunpowder, or have the knowledge to travel long distances by sea. Nor did they possess the kind of transport that comes with the wheel, because they did not have large domesticated animals such as horses and oxen to pull them. Contact with Europeans, beginning in 1492, introduced them to new animals, crops, weapons, ships, and a wide array of ordinary objects and means of production that were previously unknown.

The English mathematician Harriot remarked that the Algonquins he met on Roanoke Island in 1585 found European clocks, compasses, and other instruments almost divine. "They thought they were rather the works of gods than of men." Of course we do not have the Algonquins' own viewpoint in this account, but it helps to capture the radical unfamiliarity with European things. Europeans also brought back objects from the New World that fascinated them: canoes, teepees, tomahawks, tobacco pipes, moccasins, and beaded and feathered headdresses and costumes.

- Alfred Crosby

- Manila Galleon

- Disease

Section Focus Question:

What was the Columbian Exchange, and what was its demographic impact on Natives?

Key Terms:

With the advent of the slave trade, Europe brought elements of Africa into the Americas as well. And, once the Spanish established in 1570 the Manila Galleon, a trade route across the Pacific between Mexico and the Philippines, they brought aspects of Asia to America as well.

Thus, in the first century of the European encounter with the Americas, the indigenous populations found their lives changing dramatically. Great civilizations collapsed in the face of war, enslavement, harsh working conditions, competition for resources, and especially disease. But these changes were coupled with transformations of the everyday fabric of their lives. Food, clothing, tools, language, and faith of a Creole society also emerged that belonged neither to the Old World nor entirely to the New.

The most dramatic and lasting change, however, was the rapid depopulation of the Americas. The Arawaks, Taino, and Caribs who encountered Eurasian diseases with the arrival of Columbus to the Caribbean were nearly extinct by the mid-16th century. The most densely populated regions such as Mexico were soon depopulated by waves of epidemics — first smallpox, followed by measles, typhus, malaria, hepatitis, influenza and a host of other contagious diseases against which the Native populations had no immunity — that began as early as 1519.

A century later, the Massachusetts and coastal Maine tribes such as the Abenaki succumbed rapidly to a viral epidemic of 1616-17 that accompanied the arrival of significant numbers of English. The epidemic led Cotton Mather to declare that it was God's will that the Natives should die to make room for the colonists.

Numerous epidemics made disease one of the most endemic and horrific facts of life in the Americas after 1492. "We were born to die," one Mayan chronicler sadly reported after witnessing the rapid and awful progress of yet another unidentifiable disease. While Europeans also succumbed to unfamiliar climates, tropical diseases, and malnutrition, each ship brought more of them to America's shores, while every epidemic diminished Native populations.

It is difficult to make any precise estimate of the Indian population of eastern North America before English colonization. Our information consists of archaeological evidence from the remains of known settlements, and the observations made by European colonists in their early encounters with Native groups. Both kinds of sources require extrapolations and estimates from limited and perhaps unreliable evidence. Given these caveats, current estimates suggest that, at the time of Columbus's voyages, perhaps two million indigenous people lived in the territory east of the Mississippi River, from the thinly settled regions of Canada in the north to the more populous southern regions nearer the Gulf of Mexico.

- Mound builders

- Native agriculture

- Pueblos

- Pueblo Revolt

- Atahualpa

- Powhatan Confederacy

- Iroquois Confederacy

Section Focus Question:

What were some of the characteristics of major Native groups in North America: Algonquin, Iroquois, and Pueblo?

Key Terms:

As Europeans traveled further northward in the 16th and 17th centuries, they experienced a world quite different from the Mesoamerican civilizations with which they became familiar in the early 16th century. The French cosmographer André Thevet included a portrait of the man he considered to be the King of Florida, Paraovsti Satovriana. He placed him next to Mexican leader Motecuhzoma, the Inca ruler Atahualpa, and the Europeans who pioneered the exploration and conquest of the Americas in his True Portraits of Illustrious Men (1585).

In the region of the Americas that became the United States, perhaps the most sophisticated civilizations were in the Mississippi and Ohio River Valleys. In Louisiana on a series of mounds overlooking the Mississippi River, archaeologists have found evidence of an ancient civilization beginning about 3,000 years ago. It had formed trade networks that extended up the Mississippi River to modern-day Minnesota. Successive mound-building civilizations continued in the Mississippi River Valley, including a flourishing civilization between 900 and 1300 CE.

Many of the tribes Europeans encountered, especially those south of the Ohio River, the most densely populated portion of the continent, were descendants of these earlier groups. Mississippian societies had declined with the beginning of the Little Ice Age of the 14th century and dispersed into smaller regional nations or confederations. The Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto was one of the first Europeans to see the evidence of this civilization during a 1539-43 expedition to claim this territory, a journey from which he did not return.

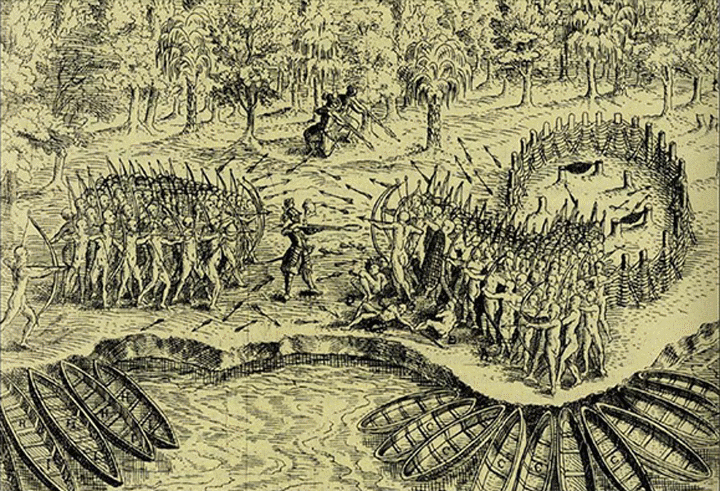

Other substantial confederations in North America included the Iroquois-speaking people of the southern Great Lakes region. The Native tribes with whom the French explorer Samuel de Champlain made alliances in the development of the French Canadian fur trade, and are called today "First Nations," included the Huron, Montagnais, and Etchemin, all of whom were hostile to the Iroquois. Champlain's battle in support of his allies, which occurred in upstate New York in the vicinity of Fort Ticonderoga on July 30, 1609, led to the death of three Iroquois chieftains and endemic hostilities between the French and the Iroquois for years to come.

In the Southwest, the Hopi and Zuni people in Arizona managed the increasingly arid climate by living in large groupings in canyons and building canals and dams to bring water to their fields. The Spanish were so impressed with their towns and five-story houses that they called them the Spanish word for town, pueblo. The Pueblo Indian villages date back to as early as the 11th or 12th centuries and the pacification and reorganization of these peoples was a major part of Onate's duties as provincial commander in 1598-1607. Later Franciscans continued the effort to pacify the Pueblo people, which led to one of the major and more successful insurrections of Natives against European rule — the Pueblo Revolt of 1680.

Some early encounters, however, did not lead to resistance or persistence. Sometimes the indigenous group simply disappeared, as was the case with the Paspahegh people whom Virginia's colonists encountered in 1607. Part of the Powhatan confederacy of the Chesapeake, which in total contained approximately 14,000 Native inhabitants, the Paspahegh had welcomed the English colonists. But this short-lived harmony dissolved under the inevitable strain of competition for scarce resources, misunderstandings, and escalating hostilities. By 1610 few if any members of this tribe lived in the vicinity of Jamestown.

There were similar stories in New England, where Puritan immigrants would soon arrive in 1620. The Native population of New England was estimated at approximately 100,000 at the end of the 16th century, but quickly declined in the coming decades. The more aggressive tactics of the English, coupled with the effects of disease, help to explain why British North America became a landscape with fewer surviving Natives than either Spanish or French America.