American Imperialism, 1870-1920

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

How did the United States move toward a full imperialist policy between 1865 and 1920?

- US imperialist interests at the end of the 19th century

- Early signs of US imperialist interests

- Theorists and Social Darwinism

- Cuba and Spain conflicts and world stage

- Naval Act of 1890 and production level

- Frontier Thesis and westward expansion

- Theodore Roosevelt on Alfred Thayer Mahan

- Reconstruction and westward expansion

Section Focus Question:

What motivated the American government to begin imperialist policies in Latin America and Asia?

Key Terms:

During the time of Reconstruction, the US government showed no significant initiative in foreign affairs. Western expansion and the goal of Manifest Destiny still held the country’s attention, and American missionaries proselytized as far abroad as China, India, the Korean Peninsula, and Africa, but reconstruction efforts took up most of the nation’s resources. As the century came to a close, however, a variety of factors, from the closing of the American frontier to the country’s increased industrial production, led the United States to look beyond its borders. Countries in Europe were building their empires through global power and trade, and the United States did not want to be left behind.

Imperial Ambitions

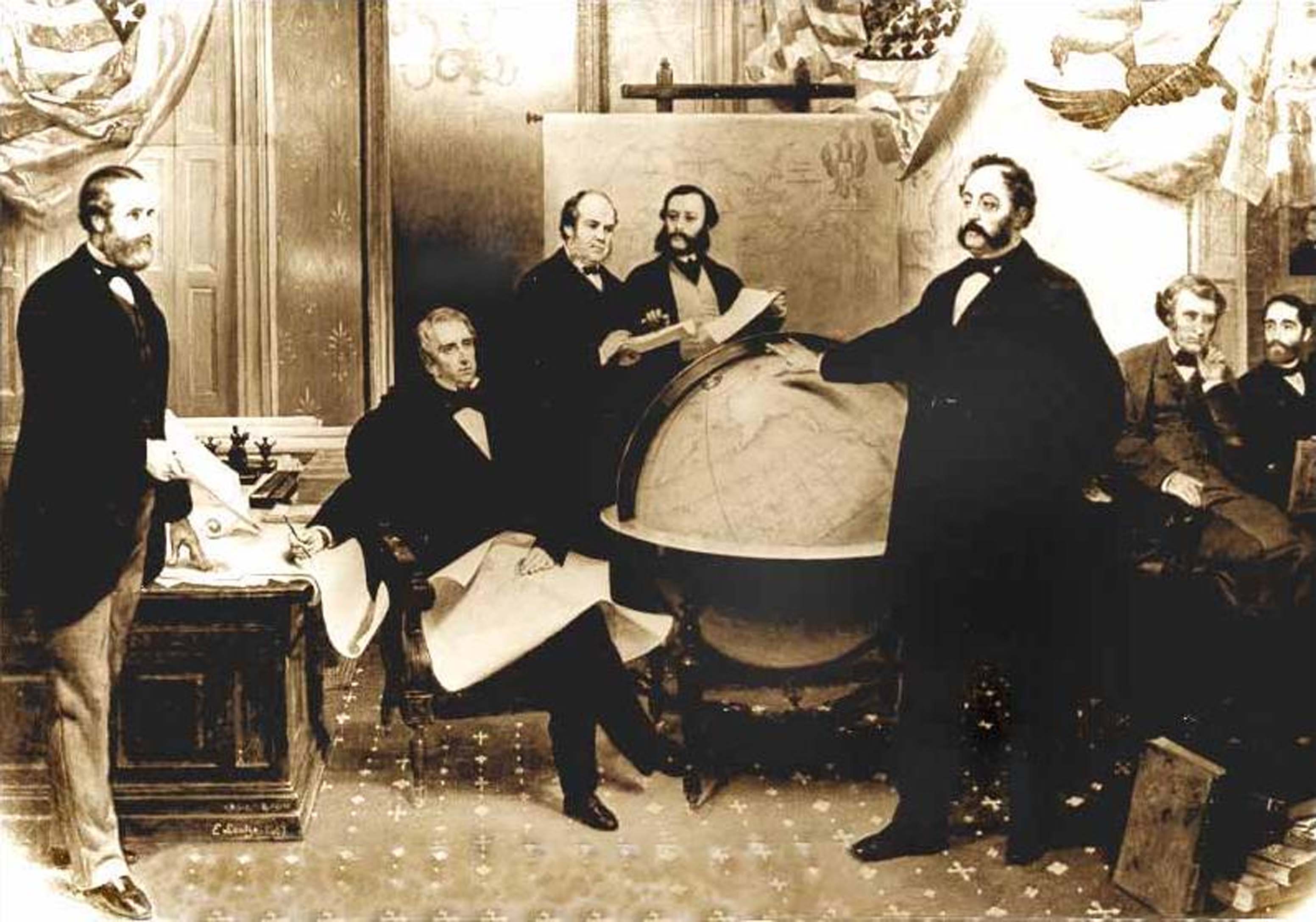

Following the devastation of the Civil War, America had no ability and little desire to take a prominent place on the world stage. Despite this, as the country began to recover slowly and reconstruct, the government began to make policies to extend American political and commercial influence in Asia and Latin America. These moves included establishing treaties with Nicaragua and annexing the Midway Islands in the Pacific to protect trade routes with Asia. Successive secretaries of state took a cautious approach to foreign policy. This attitude arose following the scorn heaped on William Seward for obtaining the Alaskan Territory from Russia in 1867, and it was only partly mitigated by the riches discovered in the Klondike Gold Rush. His successor, Hamilton Fish, steered a middle course, cautiously building an American empire of influence without creating any unnecessary military entanglements.

Despite caution from the government, business, social, and religious interests began to set the stage for an American empire in the closing decades of the 19th century. As a new industrial United States began to emerge in the 1870s, economic interests began to lead the country towards a more expansionist foreign policy. American companies pursued new markets for export as well as new sources for the raw materials that were needed to fuel its industrial growth. Religious leaders and progressive reformers also looked abroad for new “markets” for their ideas. Progressive reformers sought to spread American ideas of progressive democracy, although these efforts were often driven by at best a paternalistic attitude towards foreigners. At worst, they were driven by the influence of Social Darwinism and the idea that it was the “white man’s burden” to spread civilized ideas to lesser races. Their efforts were complemented by American Protestants, whose missionary efforts to spread the gospel and American values were often intertwined. Both progressive reform and religious proselytizing offered a new role for American women in empire-building, as around 60 percent of the missionaries who traveled abroad were women.

By the end of the 19th century, new leaders who had come of age after the Civil War pushed to pursue a new vision of an American empire. Unlike their war-weary predecessors, new leaders were eager to be tested in international conflict and hoped to prove America’s might on a global stage. As a result of their influence, the Naval Act of 1890 set production levels for a new, modern fleet that would give the United States the third most powerful navy behind only Great Britain and Spain. When commercial interests in Hawaii were threatened by native Hawaiian leader Queen Liliuokalani, the US moved swiftly to annex the island in 1898 and expand its influence in Samoa and other Pacific islands.

The Spanish-American War and Overseas Empire

- Motivations for the Spanish-American War

- Creation of the japanese state of Manchukuo

- The Platt Amendment and Cuba

- Symbolism of Uncle Sam as iconic figure

- Open Door policy and China

- Purpose of the Teller Amendment

- Sugar interests and the Spanish-American War

- Annexation of Puerto Rico and Spanish-American War

Section Focus Question:

What were the policies of the American government at the turn of the century that led directly to American imperialism?

Key Terms:

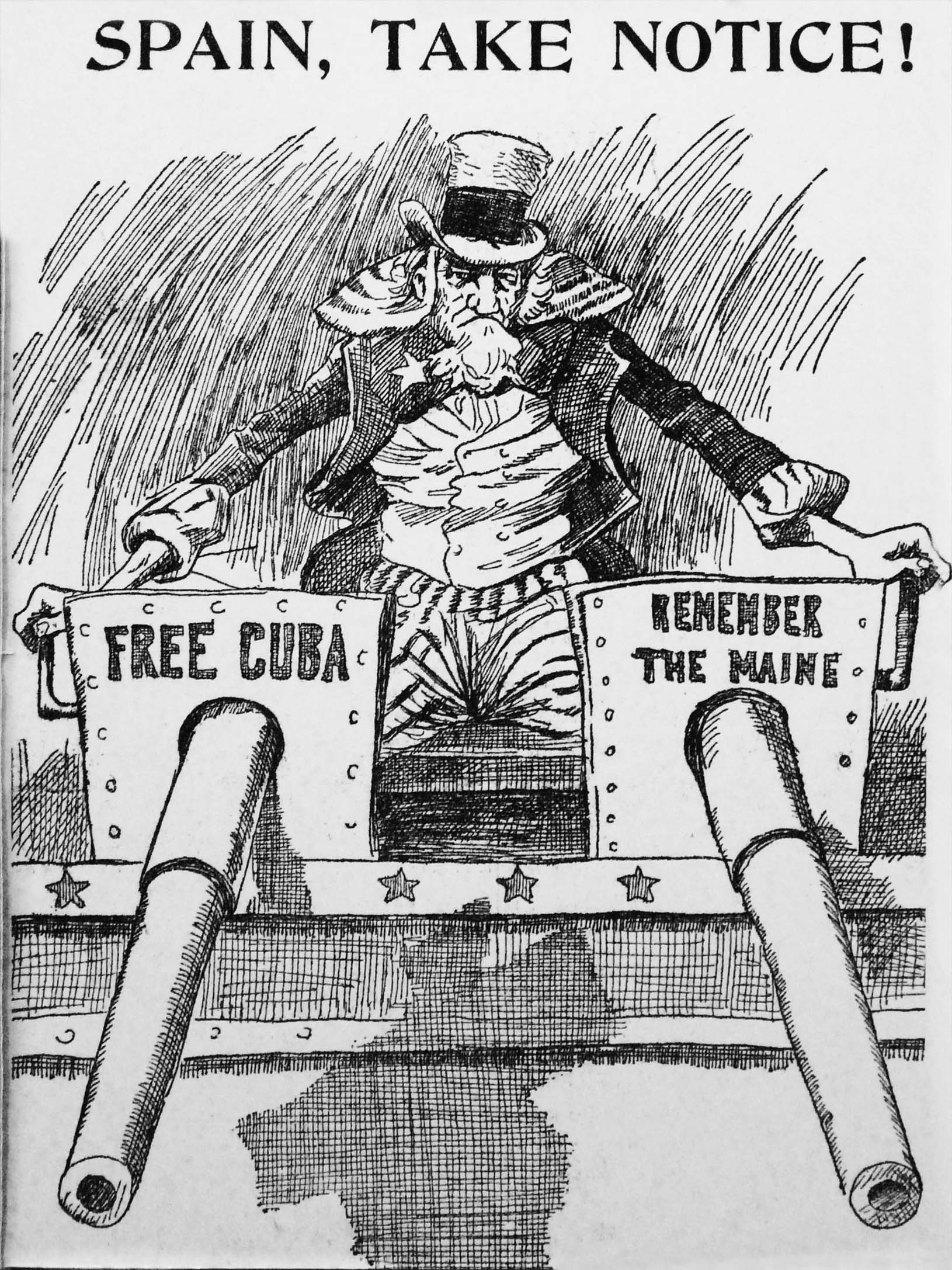

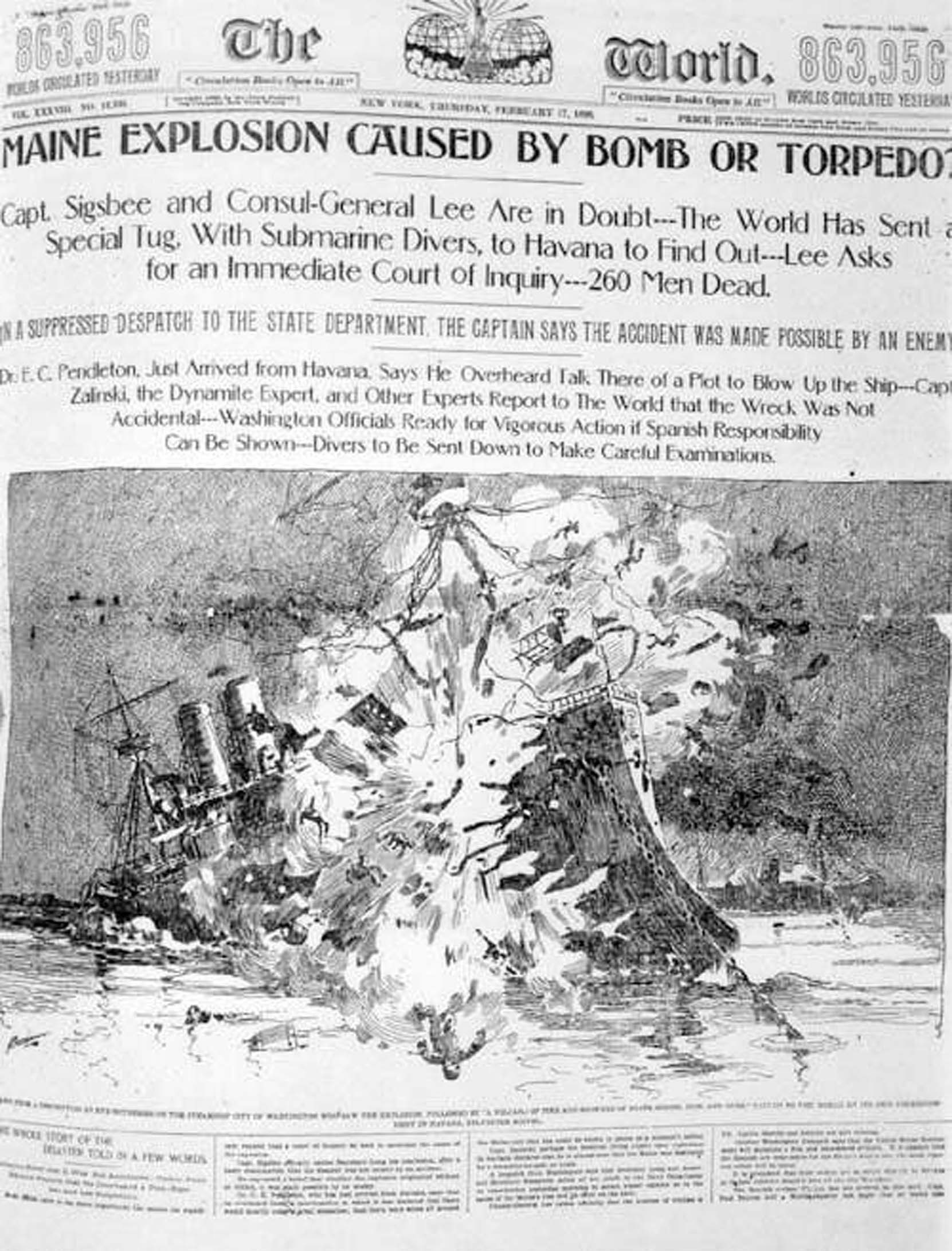

During the Spanish-American War (1898), America took the opportunity of an ongoing conflict between Spain and Cuba to assert its presence on the world stage and demonstrate that it had built a formidable military power. The United States was initially sympathetic to the Cuban independence movement led by Jose Martí because it echoed their own war for independence. However, the desire to intervene in the conflict was also driven by the need to protect US sugar interests on the island. Seeing an opportunity to drive sales with the kind of sensational copy provided by war, the newspaper industry inflamed the public to push a reluctant President McKinley towards intervention. This pressure increased to a fever-pitch after the USS Maine was destroyed in an explosion while anchored off the coast of Cuba in 1898.

Although later investigations determined that the cause of the explosion was likely an accident caused when gunpowder stored on board was ignited by the ship’s boilers, the death of 258 American sailors was used by newspapers and the public to push the case for war.

When Spain rebuffed McKinley’s efforts to make peace by brokering a deal for Cuban independence, he finally pushed Congress for a declaration of war. On April 19, 1898, Congress officially recognized Cuba’s independence and authorized McKinley to use military force to remove Spain from the island. Equally important, Congress passed the Teller Amendment to the resolution, which stated that the United States would not annex Cuba following the war, appeasing those who opposed expansionism.

The war itself was decided swiftly in just 10 weeks with the United States assisting Cuba in achieving its independence from Spain. Although the exploits of Theodore Roosevelt and his “Rough Riders” captured the imagination of the American public, the contributions of African American veteran soldiers were also significant in the eventual victory over Spanish forces. Spain had viewed the conflict as narrowly about Cuban independence, but the United States saw an opportunity to put into place the visions of American empire promoted by Mahan and other foreign policy strategists by using Spanish territories. Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt ordered navy ships to attack the Spanish fleet in the Philippines. After defeating the fleet they landed a force to take the islands from Spain. Following the destruction of the Spanish fleet while trying to escape from Cuba, the US was also able to take control of Puerto Rico.

After the war, diplomats met to broker a peace over the territories that had changed hands during the conflict between Spain, one of the original imperial powers, and the newest power with imperial ambitions, the United States. In keeping with centuries of imperial tradition, other than Cuba, neither side gave much consideration to returning control to the people of the Philippines or Puerto Rico. Spain agreed to recognize Cuban independence and American control of Puerto Rico and Guam, and reluctantly acceded to American annexation of the Philippines in return for a $20 million payout.

Although Americans whipped up by the press had largely supported the war, in the wake of this conference, prominent voices began to speak out against America’s imperial ambitions, including Jane Addams, Andrew Carnegie, and Mark Twain. This opposition almost derailed the ratification of the treaty through the Senate. An uprising in the Philippines, however, in pursuit of independence, persuaded senators to maintain a US presence in the islands. The Filipinos’ war for independence took three years to subdue, and William Howard Taft was installed as civilian governor, bringing peace by offering positions to resistance leaders and infrastructure improvements to the islands.

In the wake of these additions, American imperial expansion continued apace, with first Hawaii and Alaska, and later Puerto Rico, organized as territories of the United States. While the Teller Amendment prevented the US from formally annexing Cuba, a later amendment named the Platt Amendment secured the right of the United States to interfere in Cuban affairs if threats to a stable government emerged. The Platt Amendment also guaranteed the United States its own naval and coaling station on the island’s southern Guantanamo Bay.

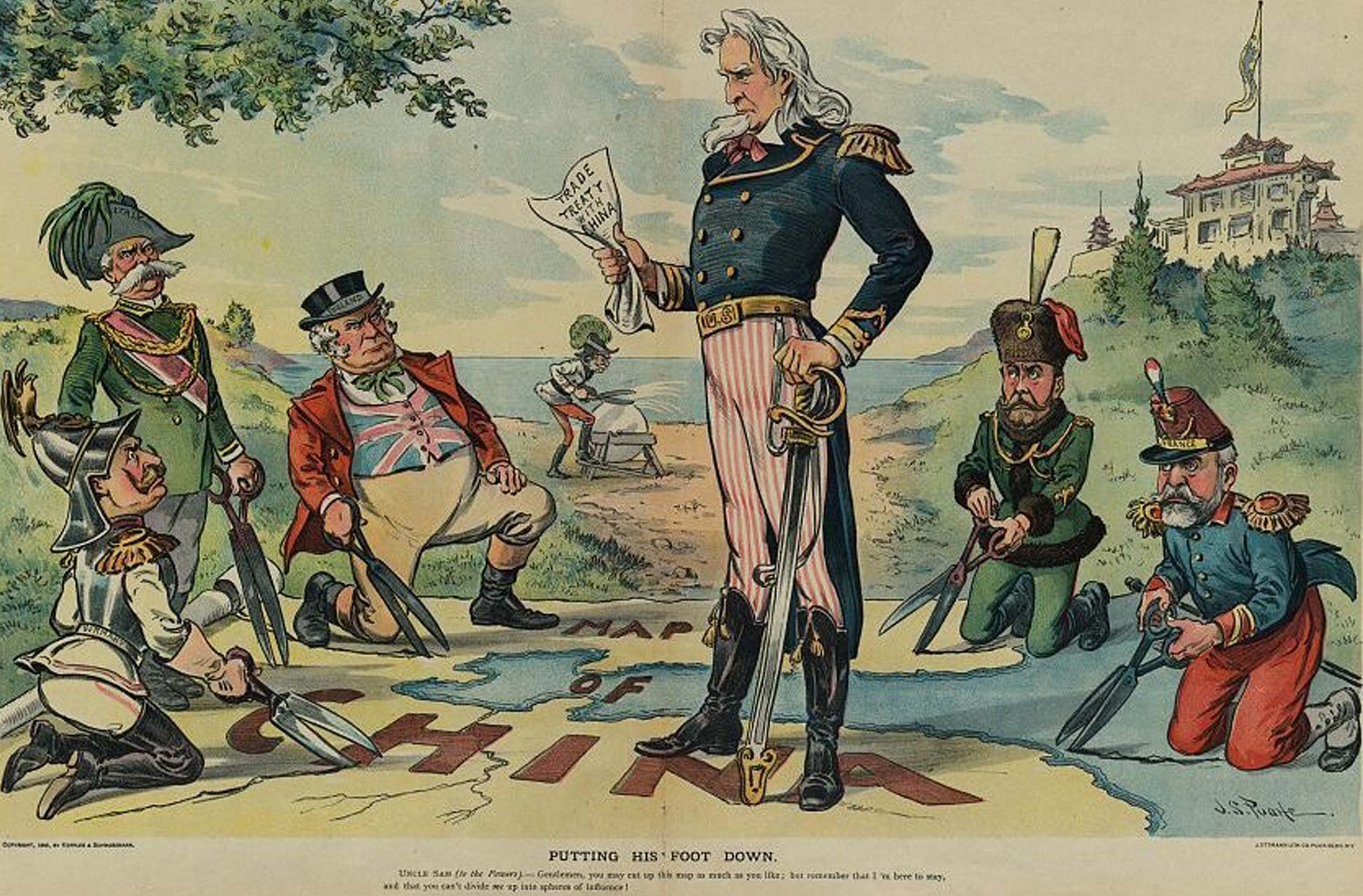

Economic Imperialism in East Asia

In addition to military expansion, the United States also continued to grow its scope and power through economic and industrial influence in the first decades of the 20th century. The defeat of the Spanish navy and expansion into the Philippines and Hawaii cleared the way for the US to pursue a more aggressive push through the Pacific into the “China Market.” Seeing a vast, untapped market for American manufactured goods, America was unwilling to settle for the kind of limited trade agreements that European powers had negotiated in the past with China, carving out the country into specific regions where each country traded. Instead, Secretary of State John Hay wrote a series of circular “Open Door Notes,” proposing that the five European powers with influence in China erase all spheres of influence and open the doors to free trade. Although these notes had little binding power, by publicly proclaiming the Open Door as official policy, Hay was able to open China to a flood of American goods.

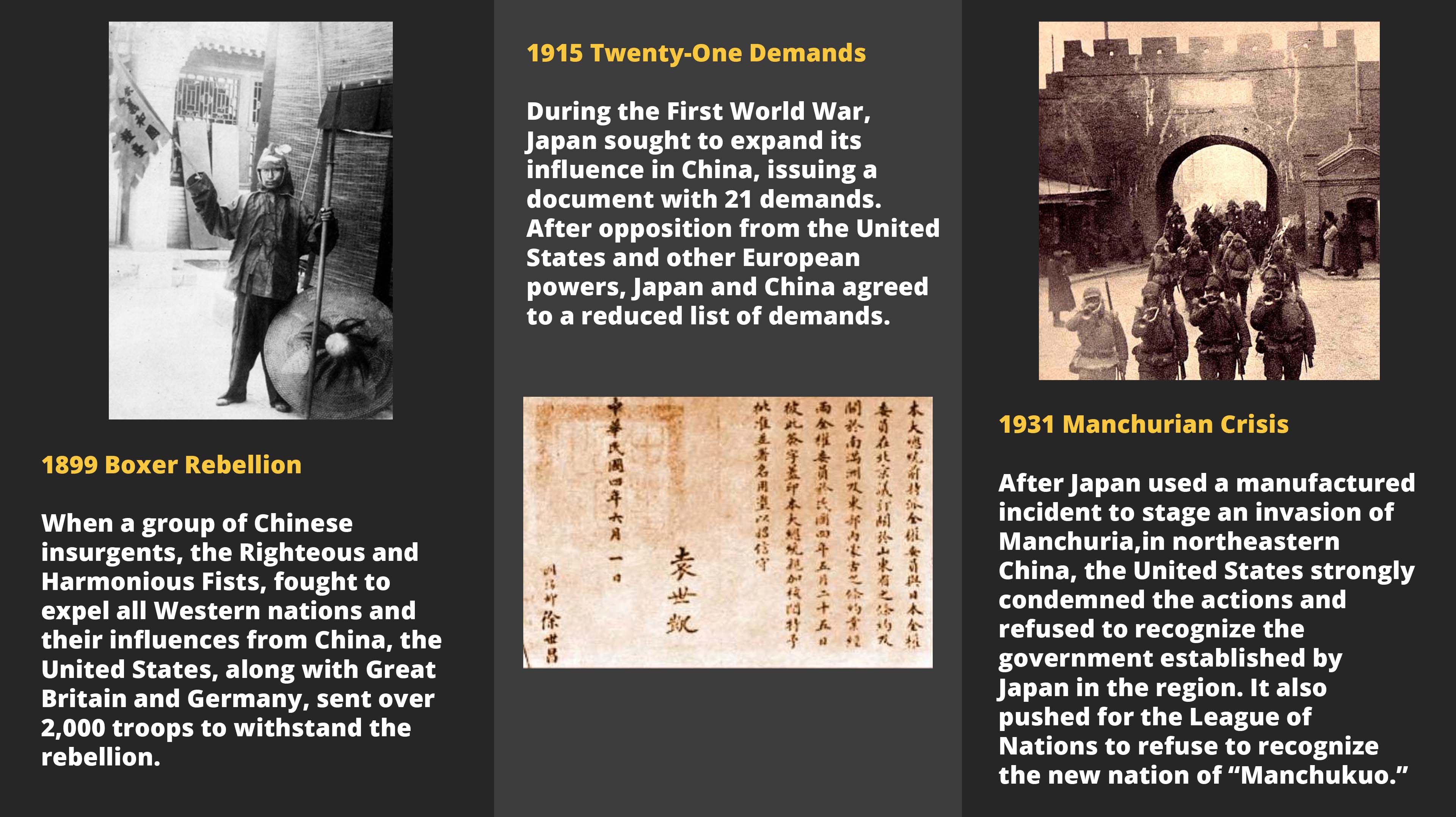

Military and economic policies mixed in China for the next half-century, as America supported China and access to its lucrative markets through uprisings and attempts from foreign powers to undermine China’s authority:

Roosevelt’s “Big Stick” Foreign Policy

- US global investment area under Taft

- Addition to Roosevelt Corollary by Taft

- President Taft and Dollar Diplomacy

- Theodore Roosevelt and the Nobel Prize

- Roosevelt Corollary and Dominican Republic

- Differences of the Roosevelt Corollary to Monroe Doctrine

- Panama Canal and world trade/military defense

- Theodore Roosevelt and the proposition of the canal

Section Focus Question:

What advantages and disadvantages did Roosevelt’s Big Stick policy and Taft’s Dollar Diplomacy have on American foreign policy?

Key Terms:

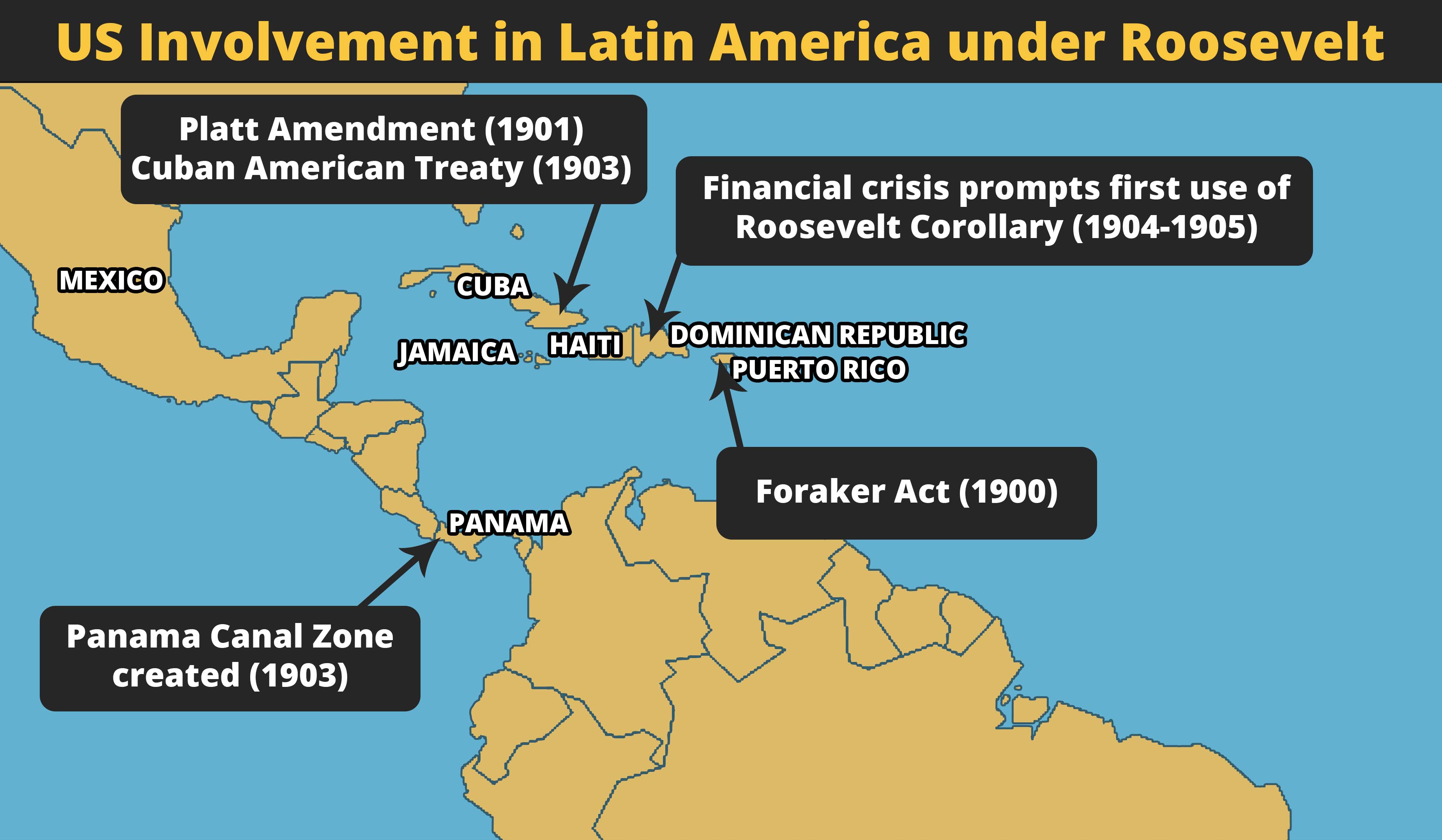

While American foreign policy during McKinley’s presidency combined military strength and economic coercion, his successor Theodore Roosevelt adopted a policy that could best be understood through his frequently quoted mantra “Speak softly and carry a big stick.” Roosevelt believed that in light of the country’s recent military successes, it was unnecessary to use force to achieve foreign policy goals, so long as the military could threaten force. His belief was that the United States had both the right and the obligation to serve as the policeman of the hemisphere — a foreign policy shaped during his administration. Drawing on an idea first proposed by his naval colleague Mahan and attempted by other foreign powers, including France, Roosevelt was determined to succeed in building a canal across the Central American isthmus. His goal was to solidify American imperial ambitions and open up a new trade route to the Pacific. To secure a route across the most favorable section of the Isthmus of Panama, Roosevelt opened negotiations with the government of Colombia. First, he deployed the policy of “speaking softly” by offering a payment of $10 million for the rights. Then he used the “big stick” of American military power to back a Panamanian revolution when they refused.

The new nation of Panama, now an American protectorate, accepted the terms previously offered to Colombia, and construction of the canal began in 1904. By installing infrastructure ahead of building efforts and drawing on medical advances to combat disease, American engineers were able to succeed where others had failed. The Panama Canal opened in 1914, permanently changing world trade and military defense patterns.

Roosevelt again combined his policies of speaking softly and carrying a big stick in what became known as the Roosevelt Corollary. Using this corollary, or updating, of the Monroe Doctrine (1823), Roosevelt sent a message to both European powers and the governments of Central and South America. He let the European powers know that their interference in the Western Hemisphere would no longer be tolerated, and he sent a message to governments throughout Central and South America that they had the support of the US. However, unlike the Monroe Doctrine, which proclaimed an American policy of noninterference with its neighbors’ affairs, the Roosevelt Corollary loudly proclaimed the right and obligation of the United States to involve itself whenever necessary.

Despite his rhetoric, Roosevelt understood that there were limitations to the “big stick” of United States military power, particularly in the East. When war broke out between Russia and Japan in 1904, Roosevelt was rewarded with the Nobel Peace Prize, the first American to be so honored, for his efforts to “speak softly” and negotiate a peace accord. Yet, when Japan continued its aggression in the region in 1906 and attempted to force American business interests out of Manchuria, Roosevelt did not hesitate to send American military to intervene, despite the distance. Directing the US Great White Fleet to carry out maneuvers in the western Pacific Ocean as a show of force from December 1907 through February 1909, Roosevelt demonstrated his mastery of both the carrot and the stick of foreign policy to maintain American influence in Asia.

Taft’s Dollar Diplomacy

Reflecting his business-oriented administration, President William Howard Taft adopted a different approach to foreign policy and imperial expansion than his predecessor Roosevelt. In a philosophy that became known as “dollar diplomacy,” Taft used American economic power to expand and protect American imperial interests in the Western Hemisphere and beyond. Taft replaced Roosevelt’s “big stick” with the “big checkbook,” paying off the debts of Central American countries so that European powers would have no reason to intervene in the region. For those nations that objected to becoming indebted to the United States, such as Nicaragua, Taft offered persuasion in the form of American warships and marines. To protect American economic domination in the region, Taft proposed an additional corollary to the Roosevelt Corollary that forbade foreign corporations from obtaining strategic lands in the Western Hemisphere.

In Asia, Taft also placed economic interests at the center of his foreign policy, using American support for Chinese railroad financing and construction to push further into the Chinese market. However, this move revealed the limits and limitations of American diplomacy, placing the United States in competition with Japan and Russia. Realizing that American foreign policy needed to be specific to region, Taft oversaw the reorganization of the State Department into geographic regions.

Taft’s policies, although not as firmly based on military aggression as those of his predecessors, created difficulties for the United States, both at the time and in the future. Central America’s indebtedness would create economic concerns for decades to come, as well as foster nationalist movements in countries resentful of America’s interference. In Asia, Taft’s efforts to mediate between China and Japan served only to heighten tensions between Japan and the United States.

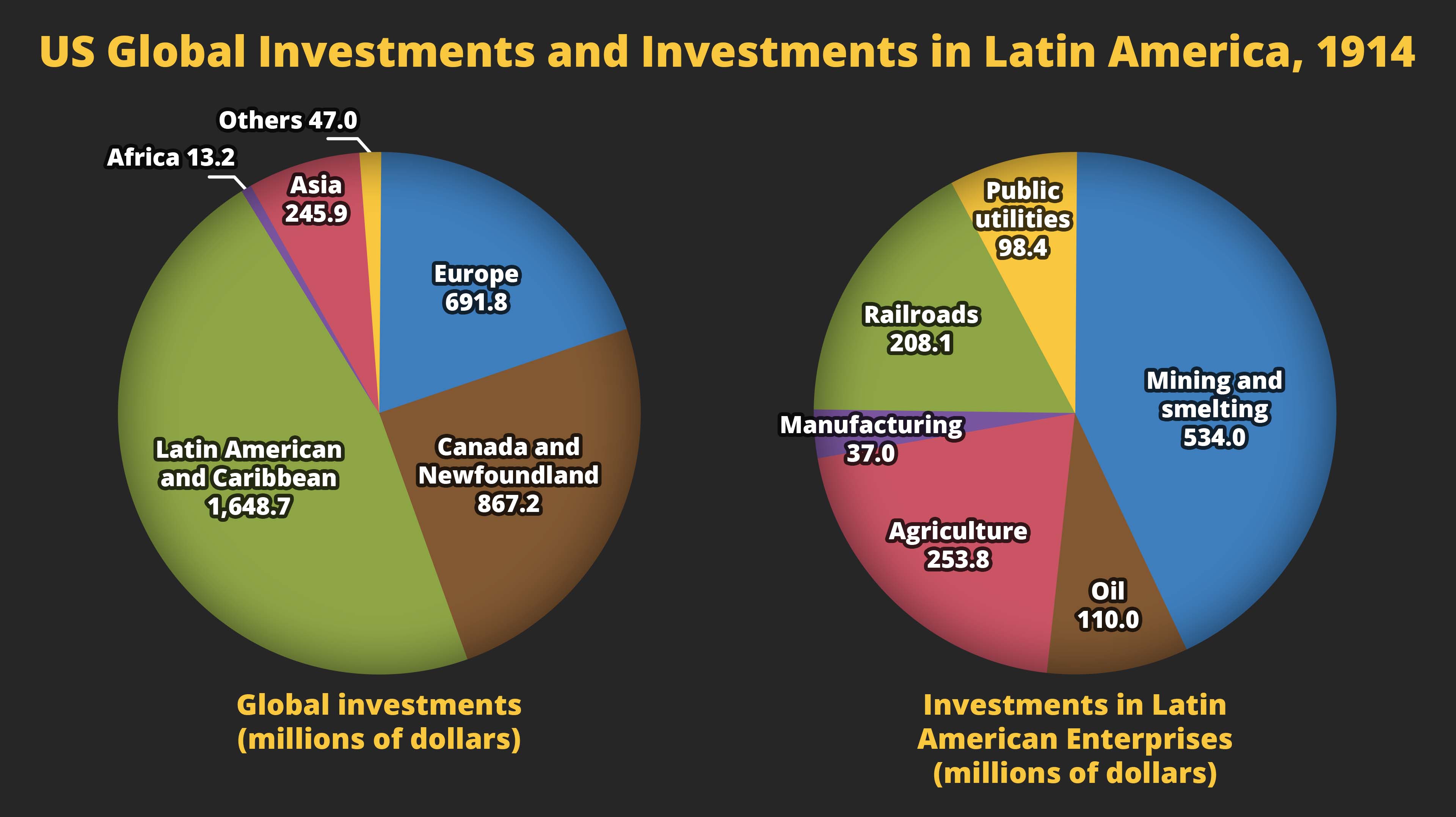

As Taft’s presidency came to a close in early 1913, the United States was firmly entrenched on its path towards empire. The world perceived the United States as the predominant power of the Western Hemisphere — a perception that few nations would challenge until the Soviet Union did so during the Cold War era. In Asia, Taft tried to continue to support the balance of power, but his efforts backfired and alienated Japan. Increasing tensions between the United States and Japan would finally explode nearly 30 years later, with the outbreak of World War II.