Reform

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

What new methods did reformers use during this period?

- Progressives push for regulation

- Farmers and negotiation power

- Reasons to join the Grange

- Goals of the Progressives

- Organizing smaller groups of social change

- First major reform organization

Section Focus Question:

How did early reform organizations emerge to combat the inequalities of the Gilded Age?

Key Terms:

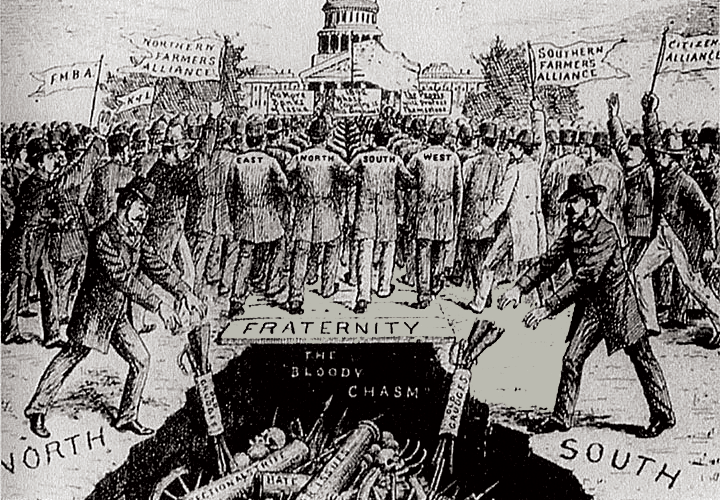

Waves of reform swept the American landscape during the last decades of the 19th century. Farmers, workers, women, and middle-class reformers responded to wrenching social changes with powerful mass movements. Many of these were "anti-monopoly" movements. They fought against corporate privilege and political corruption. They pushed for regulation and public control of the railroad, banking, and other industries. And they advocated reforms for a more equitable distribution of the nation's wealth, narrowing the gap between rich and poor, and shifting resources from the financial centers of the Northeast to the rest of country. But these movements also focused on a host of other causes, from women's rights, to the prohibition of alcohol.

As businesses combined into large corporations, millions of ordinary citizens built their own organizations. They joined a wide array of fraternal orders, unions, leagues, and clubs. Such voluntary associations marked one of the most telling features of the age. They also served as building blocks of reform that would play a major role in the making of modern America.

The nation's farmers were among the first to organize. Farm families often struggled to get by in remote and desolate places. They toiled under the hot sun and faced plagues of boll weevils and grasshoppers. A deflationary price spiral and tight credit caught them in the scissors of low prices for their crops and high interest rates on the debts they owed for supplies and machinery. At the same time, isolated farmers had little negotiating leverage with the railroads, grain dealers, and merchants who they relied on to transport and market their crops and supply their farms.

In this context, farmers looked to combination and joint efforts to improve their lives. The Patrons of Husbandry, or the Grange, marked the first major breakthrough in large-scale organization. Formed in 1867, by the mid-1870s the Grange had nearly 800 thousand members across the country. Grangers set up cooperative stores, grain elevators, cotton gins, insurance agencies, and trading companies. They turned to cooperation to gain economic leverage and strengthen the commercial position of the American farmer.

Officially the Grange was not political. In practice, however, it served as a powerful farmers' lobby. Committed to rural education, the Grange campaigned to improve public schools and land-grant universities. It fought for state regulation of the railroads and freight rates, as well as grain elevators. During the 1870s, such regulations, known as "Granger Laws," were adopted by states from Illinois to California. Although the Grange soon declined, its example provided a model for future efforts at farm organization.

The Farmers' Alliance proved even more powerful and bold than the Grange. With roots in central Texas, by 1890 the Farmers' Alliance claimed 1.2 million members in 27 states from coast to coast. It conducted a massive campaign of adult rural education, and experimented with large-scale cooperative marketing schemes. It also pressed for government intervention in the economy to better serve the interest of farmers.

- The Grange and support of white planter class

- Post-Haymarket riot and American trade movement

- Involvement of Reform movements

Section Focus Question:

What specific policies did farm organizations and labor movements advocate to hold back the power of big business and elevate the common man?

Key Terms:

Its most unique proposal was the so-called "Subtreasury," a plan for the federal government to build warehouses in farm districts across the country, and to provide low-cost loans to farmers on their stored farm products. Besides the Farmers' Alliance, similar farm associations took root. Never before had American farmers been organized so effectively.

Farmers' organizations demanded equal rights for farmers within the national economy, but they tended to exclude African-American and non-white members and to reject their claims for civil rights. In the 1870s, the Grange supported the efforts of the white planter class to overthrow the bi-racial Reconstruction governments in the former Confederacy. This support of white power tended to set a pattern for other reform movements including the Farmers' Alliance.

Although there was also a Colored Farmers' Alliance, its members tended to be poor sharecroppers or laborers. In contrast, the members of the white Alliance were usually land-owning farmers. The two Alliances were separate and unequal, and the white Alliance supported adoption of the segregation laws.

The labor movement was not far behind in building an organization. Trade or craft unions organized carpenters, railroad engineers, and similarly skilled workers. The most striking development, however, was the rise of the Knights of Labor. Formed in 1869 among Philadelphia garment cutters, by the mid-1880s it was the largest labor organization on either side of the Atlantic.

Part of the reason for the Knights' success was that it organized women, African Americans, immigrants, and unskilled workers who were excluded from the craft unions. There was one exception: the Knights were openly hostile to Asian immigrants. Working class communities joined the Knights' local lodges, while in the industrial districts, the Knights organized coal miners and railroad workers. They effectively challenged corporate power with the organized power of labor.

- Social Darwinism and justification for inequalities

- Goal of the American Labor Movement

- Pendleton Civil Service Act and civil service employees

- Single-tax club and corporate power

- Author of the Gospel of Wealth

- Legislation to keep African Americans from voting

- Southern Populist Party and southern politics

- Battle of standards and burden on farmers

- Support for progressive reforms and populism

- Direct democracy and control of corporations

- Decline of Knights of Labor and trade unionism

- Members of the Knights of labor

- Significance of Haymarket Riot

- Different Progressivist parties

- Purpose of Women's Christian Temperance Union

Section Focus Question:

Why did so many small and briefly-organized political parties emerge in this period, and what did they advocate?

Key Terms:

In the spring of 1886, the Knights battled Jay Gould's railroad empire. It also joined with other labor organizations in a national movement for the eight-hour workday. This was a high-water mark of the American labor movement. The corporations struck back. Courts issued injunctions against the Knights, and employers fired and blacklisted its members. Anti-labor hysteria intensified in the wake of the Haymarket bombing on May 4 of that year. Labor organizers faced a wave of repression as a result. The Knights would not recover from the wounds of that repression. The energy of a weakened labor movement shifted to the trade unions and the emerging American Federation of Labor.

Women, meanwhile, mobilized for multiple causes in a variety of clubs and associations. The largest and most significant of these was the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). An organization of mainly Protestant and middle-class women, the WCTU had its origins in the campaign against the consumption of alcohol, which it viewed as a menace to public health.

But it took on broader interests in the 1880s and 90s, campaigning for women's suffrage, equal pay laws, and other rights for women. The WCTU also focused on alleviating poverty and problems of social justice and made common cause with the Farmers' Alliance and the Knights of Labor.

Coalitions also came together for specific reforms. Middle class and working class activists joined single-tax clubs in search of a tax remedy to curtail corporate power and rising inequality. Urban and rural constituencies formed anti-monopoly leagues and direct democracy associations that campaigned for municipal reform, civil service rules, direct election of senators, and referendum and recall — all measures to break the grip of railroad and other corporations on city governments and state legislatures.

In national politics reformers sought changes in the currency. They wanted to end the hard money of the gold standard in favor of paper money or coining silver. Historians have in the past dismissed the "Battle of the Standards" pitting "Gold Bugs" against "Greenbackers" and "Silverites" as superficial and diversionary. But reformers correctly understood that much was at stake.

Hard money meant that bankers and financiers were being paid top dollar on the credit they extended. For farmers and other debtors, hard money made it even more difficult to repay their debts. With good reason, reformers in the rural West and South believed that inflating the currency would lighten the burden of mortgages and other debts, and stem the flow of the nation's wealth to the financial centers of the Northeast.

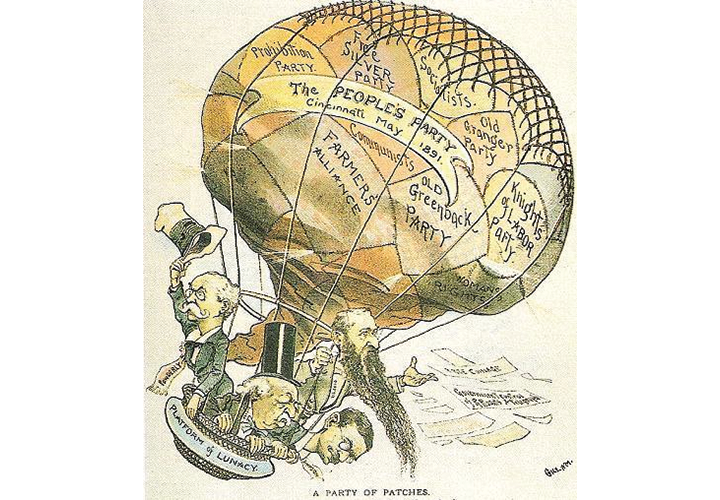

Reformers repeatedly turned to electoral politics. They did so either through one of the main parties, or through third parties such as the Greenback Labor Party, the Union Labor Party, or the People's Party (also known as the Populist Party). These parties formed in the early 1890s. The Populist Party brought together multiple currents of Gilded Age reform that included the Farmers' Alliance, the Knights of Labor, the WCTU, and tax and currency reformers. Its showing in the 1892 and 1894 elections made it the most successful third party in American history. The only exception was the Republican Party of the 1850s.

But the Populists' initial success created two dilemmas. The first of these had to do with race. Since the end of Reconstruction, the Democratic Party held a political monopoly across much of the South. The Populists, however, split the white southern vote. Competing Populists and Democrats had no choice but to appeal to black voters. This provided African Americans with political leverage in demanding school funding and other needs.

In those places where the Populists tried to accommodate such demands, the Democrats attacked them for racial betrayal. By the end of the 1890s, the Democrats had launched a violent "white supremacy campaign" demanding an end to black voting. In face of this pressure, most white Populists bent before Democratic legislation for poll taxes, literacy tests, and black disenfranchisement.