Lifespan Development

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

What is the goal of lifespan development and how is it different than the goals of earlier psychological fields?

- "Womb to tomb"

- Paul Baltes

- Life expectancy in the 20th century

- "Continuity within change"

- Interdisciplinary study of lifespan

- Plasticity

- Lifespan as a core course for professional fields

Section Focus Question:

How did Paul Baltes found the field of lifespan development and what were his goals?

Key Terms:

Womb to tomb is the phrase often associated with the lifespan perspective of human development in the field of psychology. Up until recent years, developmental scientists rarely engaged in theoretical research beyond the early years, focusing primarily on conception through adolescence. It was believed that the majority of development occurred in those first years and that a person experienced no additional changes worth investigating in the remaining years (except perhaps the decline experienced in a person’s latest years). All that changed with the research of psychologist Paul Baltes (1939-2006), who is considered to be the founder of the lifespan perspective.

This essay will first focus on the significant lifespan theories of prominent contemporary developmental scientists, Paul Baltes and Erik Erikson (1902-1994). These frameworks will provide the foundation for discussion of the individual ages and stages that received so little attention for many years: emerging adulthood, early adulthood, middle adulthood and late adulthood. In each of these stages, pertinent theories unique to each stage will also be examined.

Lifespan Theoretical Perspective of Baltes

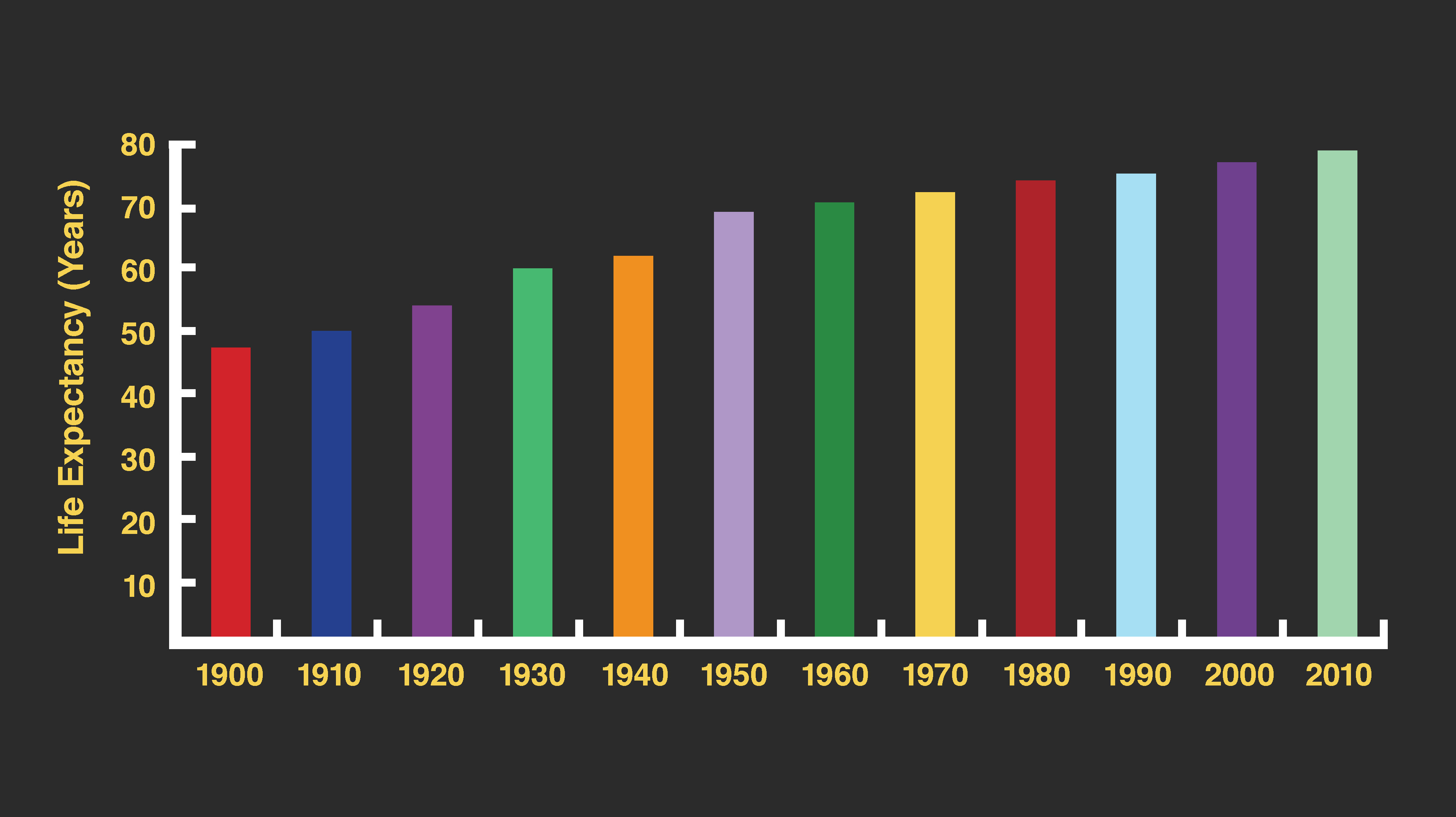

If we focus first on the main feature of Baltes’s lifespan perspective, as development being lifelong, how many years are we talking about? When we examine the average lifespan of humans through the ages, we find that it took 5,000 years for human life expectancy to extend from 18 years in prehistoric times to 41 in 19th-century England. In the US, the year 1900 marked an increase in life expectancy to age 47 and by 1915, that number had risen to 54. By 1954, we see a big jump up to age 70 and by 2013, that number rose to 78. That is an increase of 30 years in the twentieth century alone! These increases naturally led to more interest in the developmental changes experienced in these older years. Baltes was the first to develop a lifespan perspective, investigating these changes as not only being lifelong but also having the characteristics of being: multidimensional, multidirectional, multidisciplinary, and contextual.

The upper boundary of the human lifespan has remained at 122 years (oldest verified age to date) since 1997. We certainly have more centenarians (and those reaching over 100 years) than ever before, with that number continuing to increase. Baltes was the first to examine human development as being lifelong, and he was fascinated with looking at the mixture of change and constancy that occurs throughout the lifespan. The phrase he used to describe this phenomena was “continuity within change.” Reaching adulthood was not the end of development, it was the beginning of yet another stage, and Baltes viewed all the stages of the lifespan as equally important.

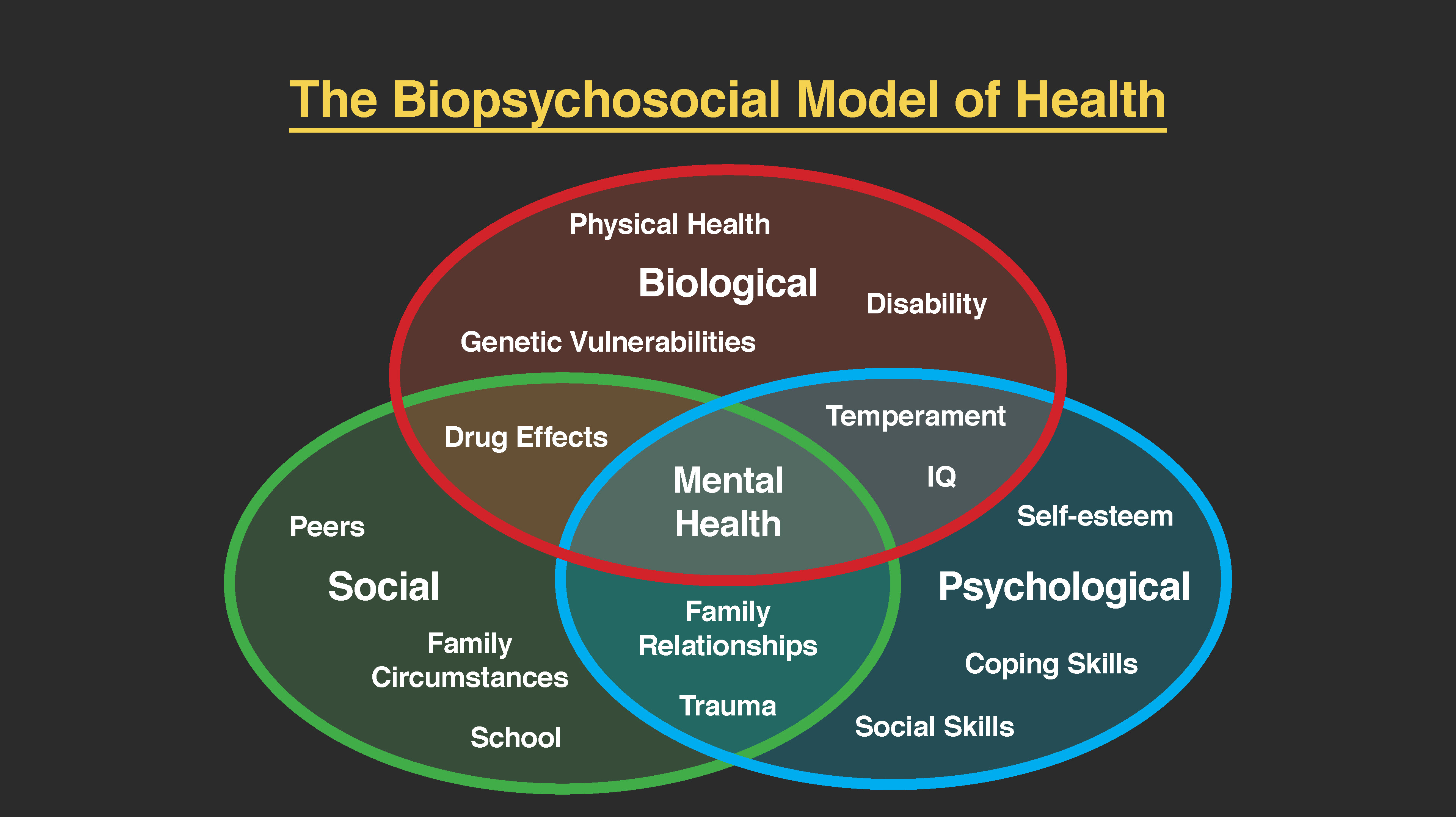

Lifespan development, according to Baltes, is both multidimensional and multidirectional. The multidimensionality aspect of his theory incorporates a blend of biological, cognitive, and social dimensions (now referred to as a biopsychosocial approach in psychology). Changes in each dimension occur at every age and one dimension influences the others. One dimension may increase while another decreases.

Baltes believed the input of several academic disciplines is required to engage in a comprehensive study of lifespan development. Psychologists, sociologists, anthropologists, neuroscientists, and medical researchers are just a sample of the professionals contributing to this area. The contextual element of development refers to the social structures in a person’s environment. Families is the most critical one, followed by school, work, peers, and many other settings. Further, each setting is influenced by economic, cultural, and historical factors, and these contexts can frequently change.

Baltes also incorporated the view that development involves growth, maintenance, and regulation of loss at different points in life. He also stressed the concept of plasticity, which refers to the ongoing capacity for change throughout the lifespan. Up until his own death, Baltes continued to focus a great deal on aging and death in his research and theoretical work.

Based on the expansion and application of the theories of Baltes, the study of lifespan development is now considered a core course for many degree programs besides psychology and education, including nursing and allied health professions and a great many other careers working with people at all ages and stages of life. Learning more about your own development, as well as the development of others in your family and life, is perhaps the greatest benefit of studying lifespan development.

Psychosocial Theory of Erikson

- Erikson's belief in social rather than sexual factors motivating us

- Erikson's emphasis on older age

- Erikson's stages of conflict resolution

- Erikson's theory of stages in early life

- Competence in elementary school

- Identity

- Cultural generativity

- Life review and late adulthood

- Isolation in old age

Section Focus Question:

What were the features of Erik Erikson's stage theory?

Key Terms:

Erik Erikson, though not as instantly associated with the lifespan perspective as Baltes, is significant to our study as he was one of the first to recognize the importance of the entire lifespan to human development. He integrated various periods of adult development into his psychosocial theory. Erikson studied and worked with both Sigmund Freud and his daughter, Anna Freud. His psychosocial theory differed from Freud’s psychosexual theory in that he believed human motivation within development to be primarily social (relationships with others), rather that sexual. Freud and Erikson are the major contributors in the general category of psychoanalytic theories, a perspective based on the unconscious processes underlying human behavior.

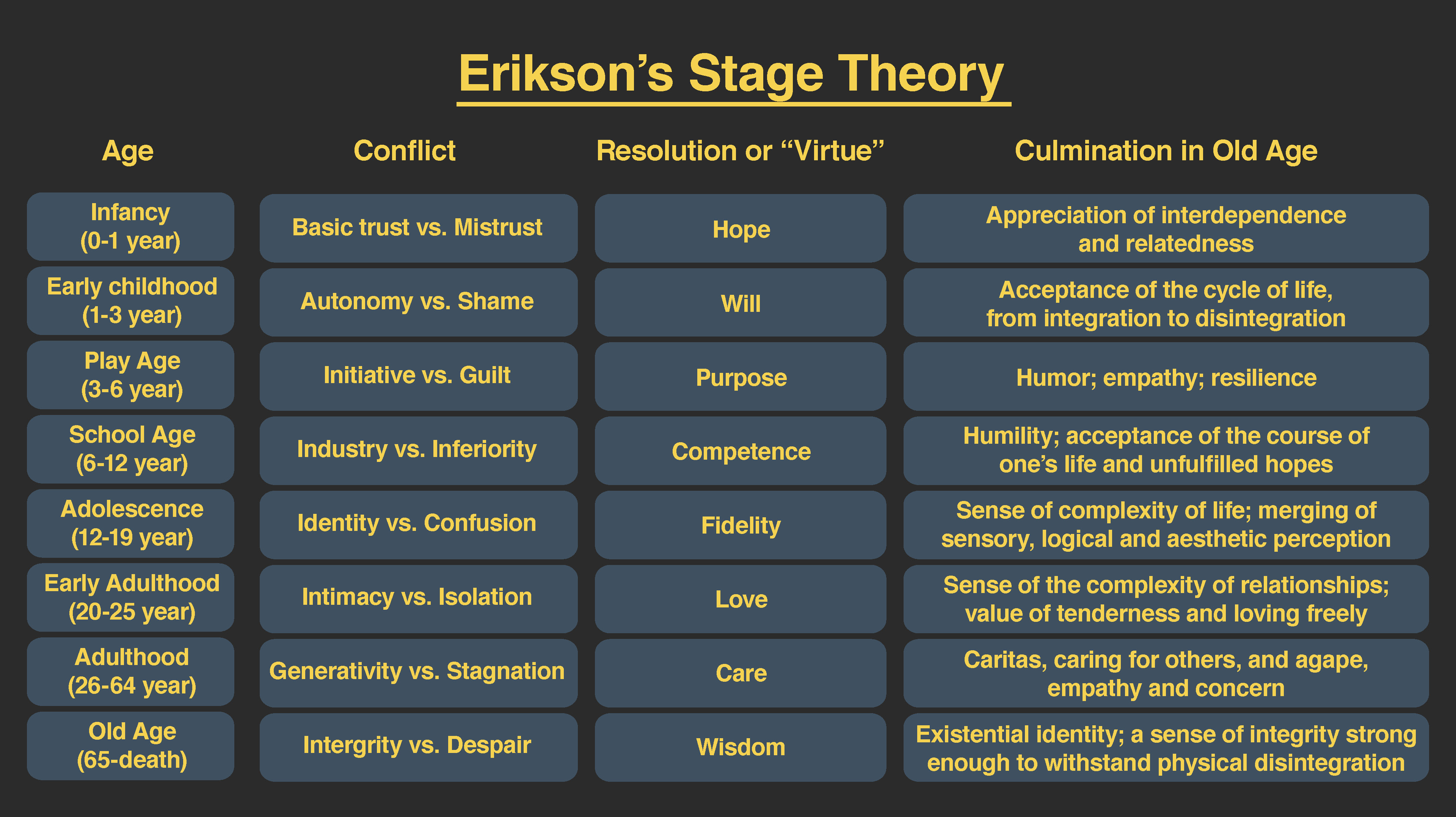

The psychosocial theory of Erikson is just as the name implies – an integration of both psychological and social features of development. Few theories up until his time combined both areas. Erikson greatly emphasized the power of nurture (the environment), not just nature (biology), in how human development unfolds across the lifespan. His general theory describes eight stages that a person goes through at certain points in their life. These stages typically occur in order, based on age, but stages can also be revisited at other times in life. So important was adult development in Erikson’s theory, near the end of his own life, he added a ninth stage to include the psychosocial stage of a person in their 80s and 90s.

Erikson’s theory centers upon stages that occur throughout a person’s life whereby they are confronted with a particular crisis to be resolved at each stage. How the individual navigates these distinct periods, where potential is enhanced and vulnerabilities are increased, results in positive or negative developmental outcomes.

The first stage of Erikson’s psychosocial theory — trust versus mistrust — takes place during the first year of life. It is in this stage that an infant learns whether or not the world is a safe place where needs are typically met. This first stage is of critical importance and the cornerstone on which the other stages are built.

Autonomy versus shame and doubt is the second stage, occurring in late infancy and toddlerhood (1 to 3 years). These little ones are just beginning to realize they have control over their behavior and have a will of their own. As they begin to assert this new independence, too much punishment or restraint can lead them to develop a sense of shame and doubt.

During the preschool years, children enter the initiative versus guilt stage. As their social world grows, more demands are placed on the child to behave in appropriate ways. Guilt may arise if a child becomes overly anxious about acting irresponsibly as new challenges arise.

Industry versus inferiority is the fourth and final stage of the early and middle childhood years, up through puberty (approximately the elementary school years). In this stage, children begin to spend a great deal of time mastering their intellectual skills. School is a huge part of their young lives. If unsuccessful in this endeavor, a child may begin to develop feelings of incompetence.

Adolescence is typically the onset of the stage of identity versus identity confusion. This period is all about answering the important questions: Who am I? Where am I headed in life? If a young person explores their roles in life in positive ways and finds a healthy path to follow, they may avoid confusion in this area.

Intimacy versus isolation is the stage of early adulthood, typically occurring when a person is in their 20s and 30s. The ability to form intimate relationships and healthy friendships helps a person avoid isolation.

Middle adulthood, when a person is approximately in their 40s and 50s, is the generativity versus stagnation stage. This stage often brings a big emphasis on parenthood and transmission of wisdom to the next generation, leaving a legacy that achieves a type of immortality. Conversely, this could instead be a period of self-absorption. The healthy resolution of this stage can be achieved in many ways through biological, parental, work, or cultural generativity. Studies indicate that healthy generativity in middle adulthood correlates with better health in late adulthood.

Integrity versus despair, the eighth stage, is late adulthood, ages 60s and onward. The critical purpose of this stage is reflecting back on one’s own life and how it was lived. When the life review is positive, wisdom is achieved rather than sadness and regret. This eighth stage is typically the last one mentioned in Erikson’s general psychosocial theory, but one more was formally added by his wife and co-researcher, Joan Erikson, following his death.

Near the end of his own life and based on his own experiences of being in his 80s and 90s, Erikson felt it important to add a ninth stage to focus on very old age (ages 80s and 90s). This stage often includes not only a loss of physical health with accompanying diminished independence but often the loss of family members and friends. These combined factors can lead to gradually becoming more and more isolated from society. The changes often result in an interesting shift of revisiting many of the earlier stages, with loss of trust, autonomy, self-esteem, and even identity. An interesting twist in this last stage is that it was possible not only to confront every one of the previous eight stages again but to do so all at the same time, with the negative side of the crisis now taking the dominant position. Despair may have an even greater role in this ninth stage than it did in the eighth stage, but the despair now may not have the luxury of a life review but is instead forced to deal with the diminished (and perhaps painful) physical abilities or unpleasant social realities encountered each day. Erikson theorized that if the very old person can move past such despair, gerotranscendence, the peaceful readiness to move on to the next stage of existence, can take its place.

Stages of Adulthood

- Stages of adult lifespan development

- Prefrontal cortex

- Passing through emerging adulthood

- Post-formal operational

- Cohabitation and marriage in early adulthood

- Positive psychology

- PERMA

- Characteristics of generativity

Section Focus Question:

How do modern lifespan psychologists describe the stages of adult lifespan development?

Key Terms:

As lifespan development theories began to take greater shape and become widely accepted in the field of psychology, the stages of early adulthood, middle adulthood and late adulthood began to receive more attention in the scientific community and in the world at large. Aspects of central importance to a particular stage led to additional research and specialization.

Early Adulthood. In recent years, the ages of approximately 18 to 25, while clearly a part of the young adulthood stage, have become segmented into a sub-stage of emerging adulthood, marking the often lengthy transition period from adolescence to adulthood. There are a great many changes that occur during these years in the domains of physical and socioemotional development.

The key biological change in emerging adulthood is continued brain development. The study of adolescence and emerging adulthood brain development is in its infancy. Technological advances will certainly further research in this area.

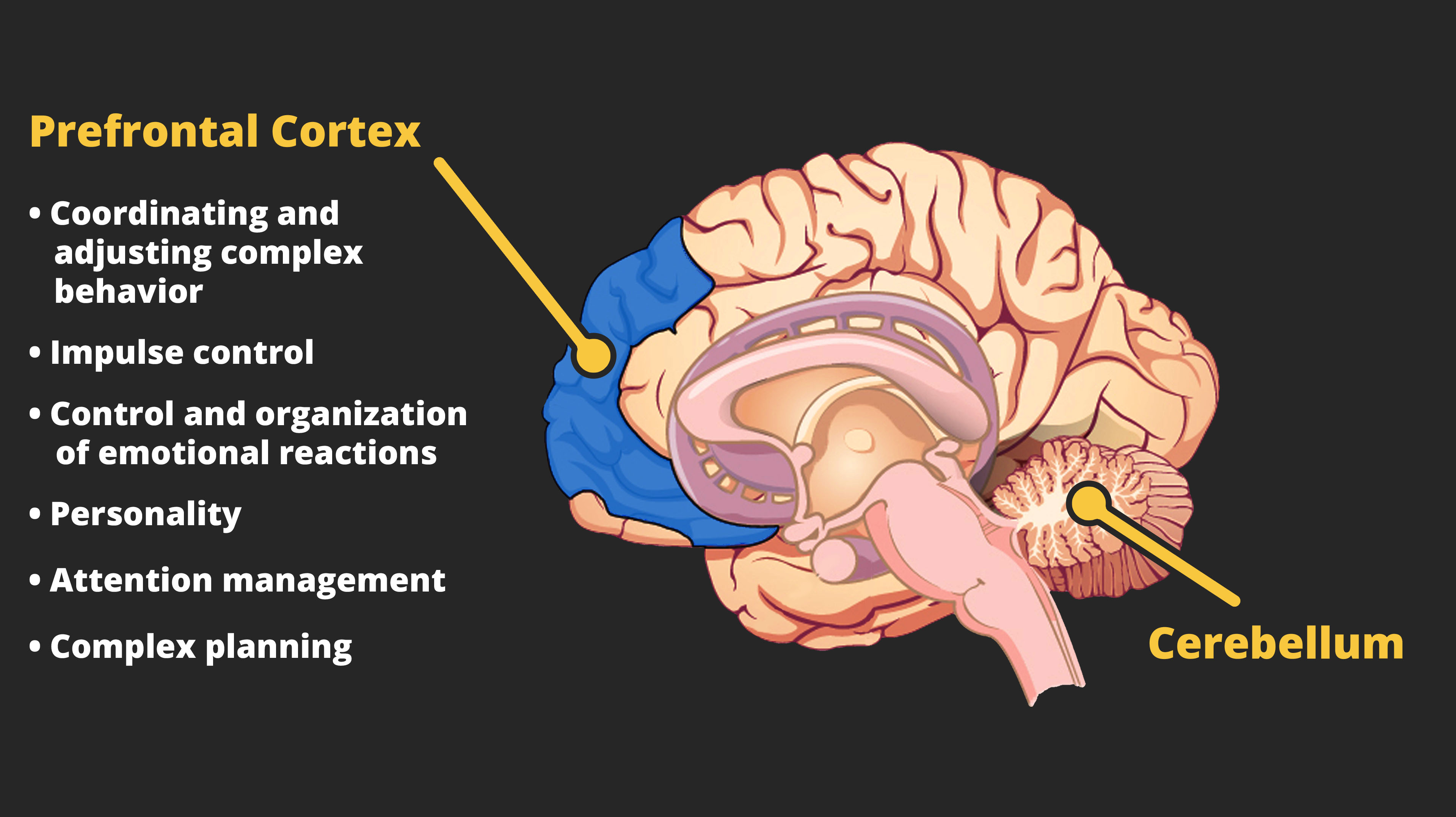

What is presently known is the brain’s ability for rewiring, plasticity, and neurogenesis (the generating of new brain cells) continues throughout the lifespan. In adolescence and emerging adulthood, significant structural changes in the brain occur. Specifically, higher-level brain functions involving the prefrontal cortex region typically mature in the emerging adulthood transition stage. This region of the brain is considered the executive center and involves decision-making, self-control, futuristic planning, and reasoning ability.

During this period, many emerging adults are making the transition from high school to college life or high school to the world of work. Jeffrey Arnett, in focused research on the socioemotional processes in emerging adulthood, found several key features of this period which involve exploring a career path, identity, and lifestyle adoption. He found there to be a great deal of instability during this time in work, education, and love. Emerging adults tend to be self-focused due to their relative lack of commitments to others and increased autonomy, coupled with feelings of being between the stages of still being an adolescent and being a full-fledged adult.

It is important to keep in mind that while these features fit a period of emerging adulthood in predominantly Western cultures, many developing nations do not have the luxury of such a transition in development between adolescence and adulthood due to early and increased life responsibilities. Research has also shown that in the United States, at-risk youth in limited socioeconomic conditions enter emerging adulthood slightly earlier than age 18.

Throughout the stage of young adulthood, the ages approximately between 18-40, a great many physical, cognitive, and socioemotional changes continue to occur.

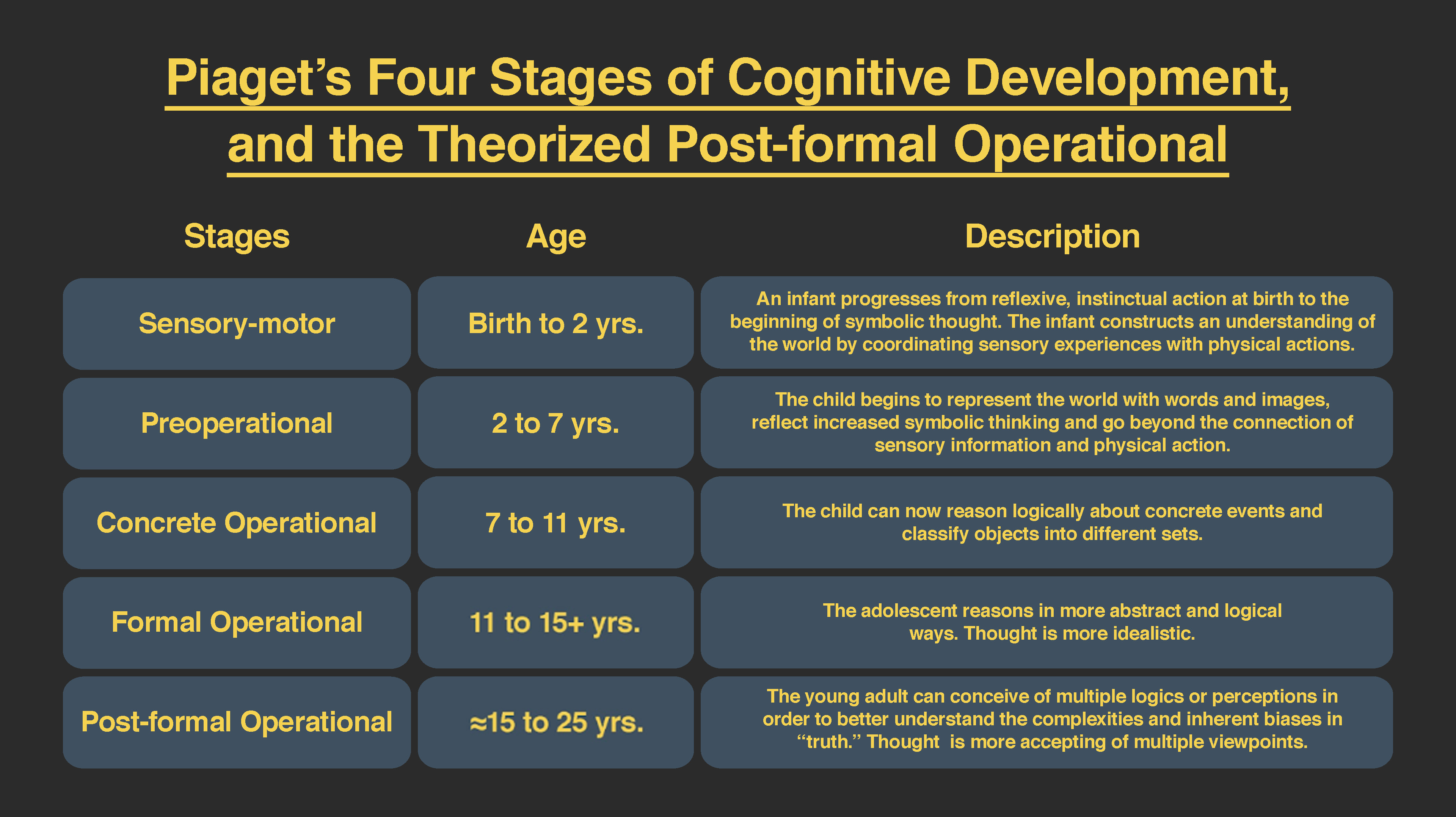

A significant area of cognitive development believed to occur during this period of early adulthood is a fifth stage that developmental theorists have recently added to Piaget’s four stages of cognitive development — post-formal thought. This stage is described as an extension of Piaget’s original stages, with an emphasis on cognition at this age being more reflective, relativistic, and contextualized. Within the post-formal thought stage, there is also an increased awareness that life events can be provisional, more realistic than formerly believed, and the new recognition that thinking is often influenced by emotion. Those in early adulthood are now confronted with making their way in the world, often for the first time in their lives. Along with that new challenge, more opportunities for problem-solving are regularly presented in daily life. Several theorists argue that to enter into this post-formal thought stage a person typically must be engaged in higher education pursuits. There continues to be more research in this area to expand these new theories of cognitive development.

The social world of early adulthood is full of relationship opportunities and changes. This may be a time when careers and work take priority along with serious intimate relationships possibly leading to marriage or cohabitation. If a person decides to have children, parenting typically begins during this stage.

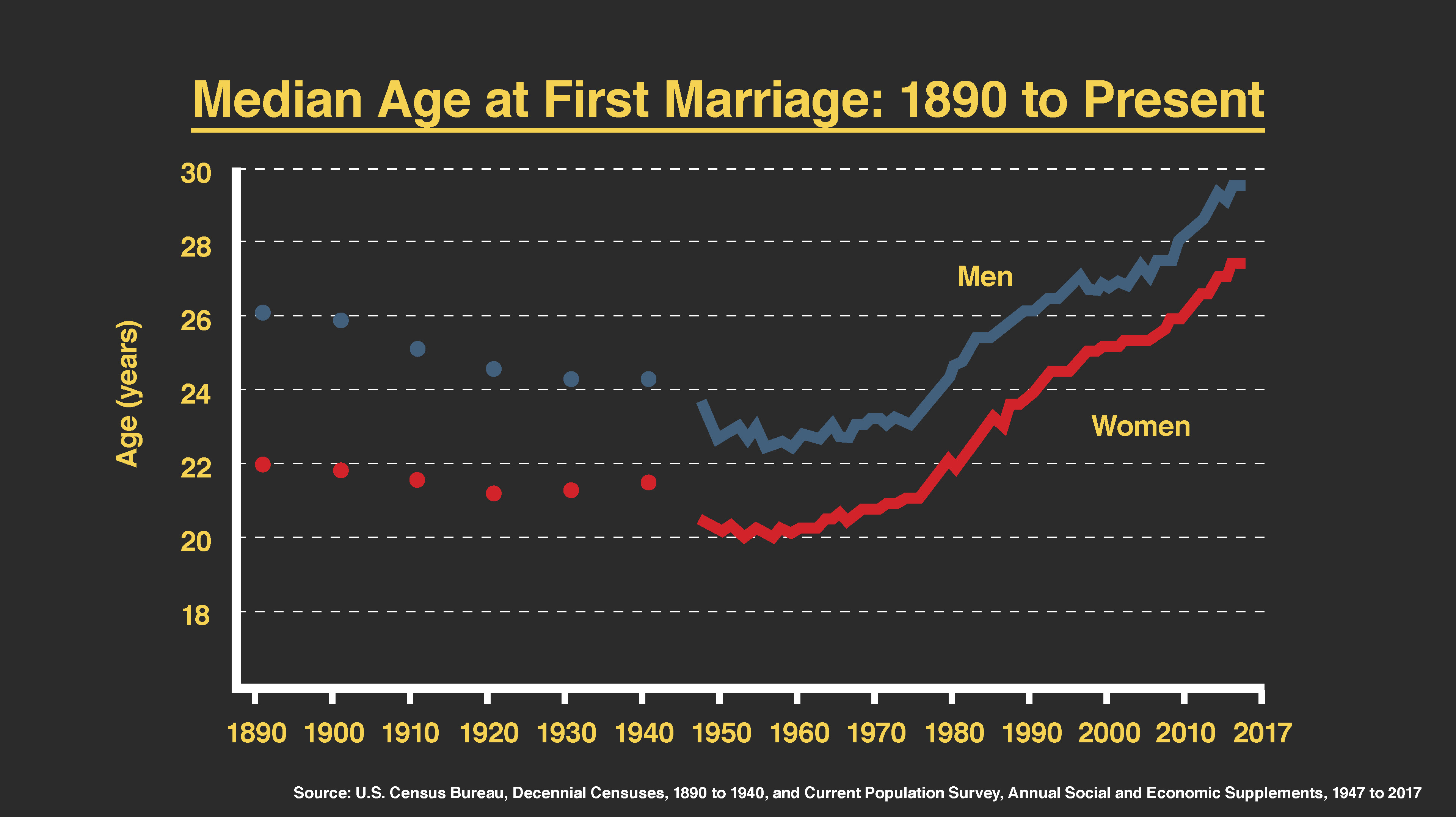

The age of marrying continues to rise. According to the US Census Bureau, the median age of marriage in 2017 in the United States was 29.5 years for men and 27.4 years for women.

More Americans than ever before are taking an alternative path and cohabiting and becoming parents outside of marriage. New figures on the demographics of cohabitation released on May 31, 2018, from the Centers for Disease Control’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) found that 64.7 percent of participants in a study of Americans age 18-44 had cohabited with a romantic partner at some point outside of marriage. There has been an 82 percent increase between 1987 and 2010 for women who reported having cohabited at some point in their lives.

W. D. Manning (2015) studied cohabitation and reports a 15 percent increase between 1997 and 2017 of cohabiting parents who started having children outside of marriage. Results also indicated that only 33 percent of children born to cohabiting parents remain in a stable family through age 12, compared to almost 75 percent of children born to married parents.

Middle Adulthood. The stage of middle adulthood is approximately the years between the ages of 40 and 65. For many, this continues to be a time of raising a family and focusing on a career. For others, it may be a time of midlife reflection prompting a change of course in order to fulfill one’s purposes and goals in life. This is often a busy time with a great deal of activity. Of particular relevance for this stage are theories from the relatively new field of positive psychology.

Considered the founder of positive psychology, Martin E. P. Seligman, professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, began intensely focusing his study in this area of human development in 1998. Positive psychology is defined as the scientific study of human strengths, traits, and circumstances which enable individuals to thrive. This flourishing occurs on multiple levels that include the biological, psychological, and social (biopsychosocial) dimensions. The theory is based on the belief that humans possess the desire to lead meaningful and fulfilling lives and are willing to cultivate the traits that will lead them to that path of well-being. It is looking at psychology through an optimistic lens of studying people who are thriving and learning how can we best help those who are not.

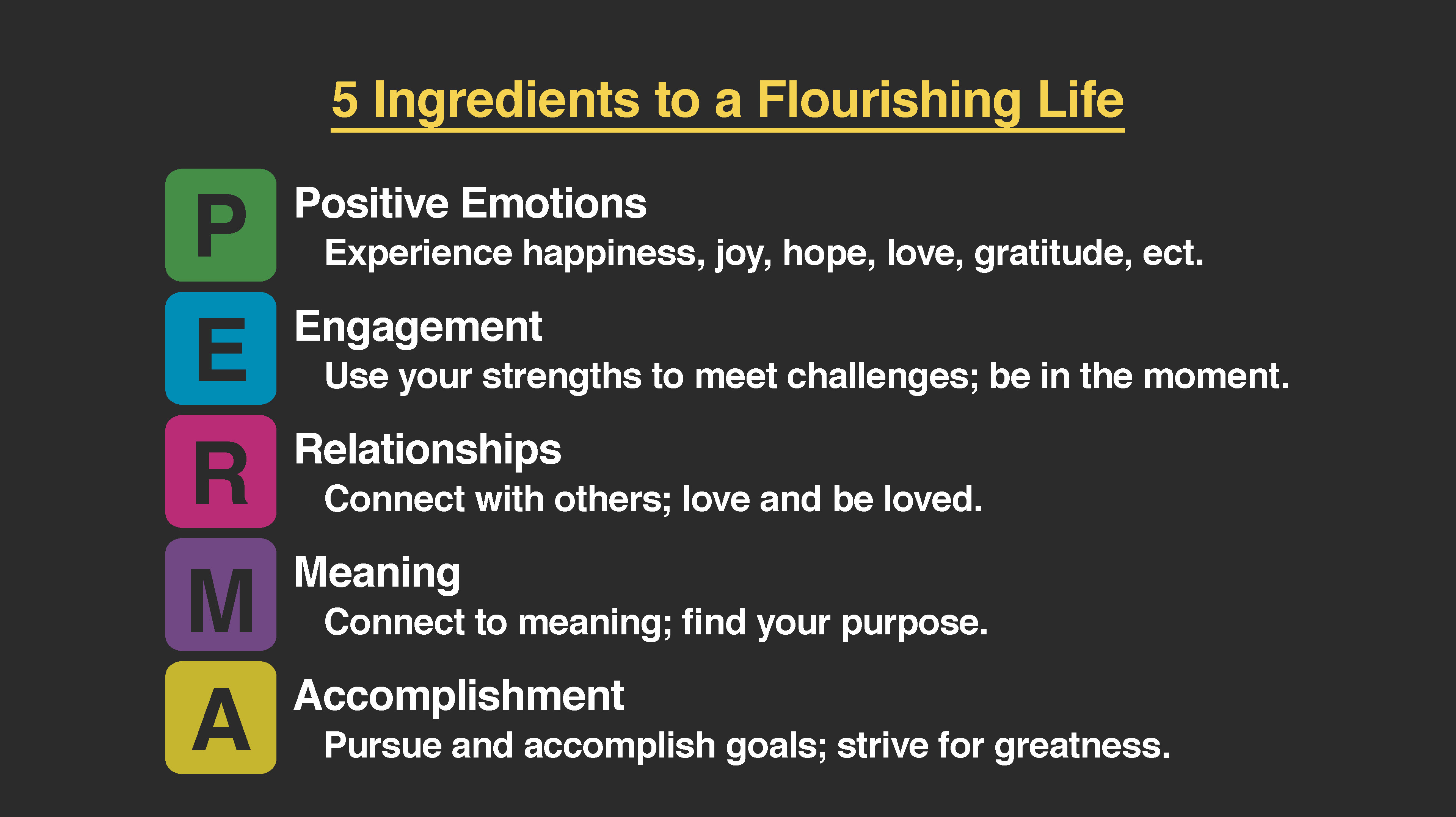

In his well-being theory, Seligman describes flourishing as the way to measure the elements of the construct of well-being. The five elements of this theory follow the mnemonic PERMA: Positive emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning and Achievement.

Positive emotion is described as what we feel, which could be enjoyable states, such as pleasure, comfort, and warmth that a person feels in the moment. Engagement includes the concept of flow. Flow is described as the process whereby a person is so deeply engaged in an activity they lose all concept of time – almost as if time stood still. It is almost as if we have merged with the object or activity during these moments of deep concentration.

Humans are social beings. It is said that other people are the key to getting through the ups and downs of life and most would agree that it is our relationships with others that give our lives meaning and purpose. The act of doing something kind for another person has been empirically shown to yield the most reliable momentary increase in the well-being of any activity tested. And as such, positive relationships are an important part of the well-being theory.

The element of meaning is described as belonging to and serving something that you believe is bigger than yourself. And the final element — achievement — describes a life dedicated to accomplishment simply for the sake of accomplishment (totally free of any kind of external demands).

Each of these five elements contributes to a person’s well-being and the overall goal of increasing the amount of flourishing in a person’s own life and on the planet. These five elements are considered the core features of the theory, with additional features identified through ongoing research, such as self-esteem, optimism, resilience, vitality, and self-determination.

Late Adulthood. The ages of 65 and beyond are considered to be the stage of late adulthood. Baltes engaged in a great deal of study on late adulthood. One area of focus was the concept of wisdom, defined as exceptional knowledge, insight and judgment about the practical aspects of life.

Baltes theorized that high levels of wisdom are rare, with only a small number of people (including older adults) attaining this high level, and their attainment required experience, practice, or complex skills. Although we think of wisdom being attained in the older years, Baltes found these and other factors to be more important than a person’s chronological age. Those individuals found to be at high levels frequently tended to place the needs of others before their own and incorporated this as an important life value (similar to a core element of Seligman’s well-being theory). And finally, personality-related factors were found to be related to high levels of wisdom. Generativity (similar to one of Erikson’s stages in his psychosocial development theory), openness to experience, and creativity predicted wisdom better than the cognitive factor of intelligence.

Baltes also studied cognitive decline in this state of late adulthood, such as the slowing down of speech, accuracy of information processing, and the diminished ability to learn new skills and knowledge. In these studies, he discovered a connection between a decline in sensory and cognitive functioning in that automatized behaviors such as hearing, seeing, and walking appeared to demand increasing cognitive resources as we grow older, thus creating the gradual slowing down.

Lifespan development, as pioneered by Baltes, forever changed the face of human development. His outstanding work throughout his career led to the identification of the processes to describe, explain, and optimize human development. No longer focusing solely on maturation until adolescence, lifespan development continues to seek to understand development as a continuous dynamic process of gains and losses lasting from conception to death