Freud and the Psychodynamic Perspective

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

What was the impact of Sigmund Freud and the neo-Freudians on the psychology of personality?

- Influence of childhood sexuality

- Differences between Freud and the neo-Freudians

- The case of Anna O.

- Freudian slip

- Superego

- Ego’s role in anxiety

- Reaction formation

- Importance of childhood according to Freud

Section Focus Question:

What were the components of Freud’s early findings about the human psychology?

Key Terms:

Sigmund Freud’s psychodynamic perspective of personality was the first comprehensive theory of personality, explaining a wide variety of both normal and abnormal behaviors. According to Freud, unconscious drives influenced by sex and aggression, along with childhood sexuality, are the forces that influence our personality. Freud attracted many followers who modified his ideas to create new theories about personality. These theorists, referred to as neo-Freudians, generally agreed with Freud that childhood experiences matter, but they reduced the emphasis on sex and focused more on the social environment and effects of culture on personality. The perspective of personality proposed by Freud and his followers was the dominant theory of personality for the first half of the 20th century.

Sigmund Freud and Psychoanalysis

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) is probably the most controversial and misunderstood psychological theorist. When reading Freud’s theories, it is important to remember that he was a medical doctor, not a psychologist. There was no such thing as a degree in psychology at the time that he received his education, which can help us understand some of the controversies over his theories today. However, Freud was the first to systematically study and theorize the workings of the unconscious mind in the manner that we associate with modern psychology.

In the early years of his career, Freud worked with Josef Breuer, a Viennese physician. During this time, Freud became intrigued by the story of one of Breuer’s patients, Bertha Pappenheim, who was referred to by the pseudonym Anna O. Anna O. had been caring for her dying father when she began to experience symptoms such as partial paralysis, headaches, blurred vision, amnesia and hallucinations. In Freud’s day, these symptoms were commonly referred to as hysteria. Anna O. turned to Breuer for help. He spent 2 years (1880–1882) treating Anna O. and discovered that allowing her to talk about her experiences seemed to bring some relief of her symptoms. Anna O. called his treatment the “talking cure.” Despite the fact that Freud never met Anna O., her story served as the basis for the 1895 book, Studies on Hysteria, which he co-authored with Breuer. Based on Breuer’s description of Anna O.’s treatment, Freud concluded that hysteria was the result of sexual abuse in childhood and that these traumatic experiences had been hidden from consciousness. Breuer disagreed with Freud, which soon ended their work together. However, Freud continued to work to refine talk therapy and build his theory on personality.

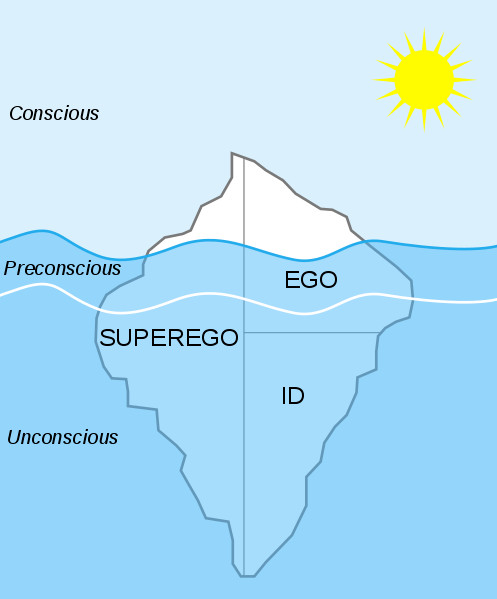

To explain the concept of conscious versus unconscious experience, Freud compared the mind to an iceberg. He said that only about one-tenth of our mind is conscious, and the rest of our mind is unconscious. Our unconscious refers to that mental activity of which we are unaware and are unable to access. According to Freud, unacceptable urges and desires are kept in our unconscious through a process called repression. For example, we sometimes say things that we don’t intend to say by unintentionally substituting another word for the one we meant. You’ve probably heard of a “Freudian slip,” the term used to describe this. Freud suggested that slips of the tongue are actually sexual or aggressive urges, accidentally slipping out of our unconscious.

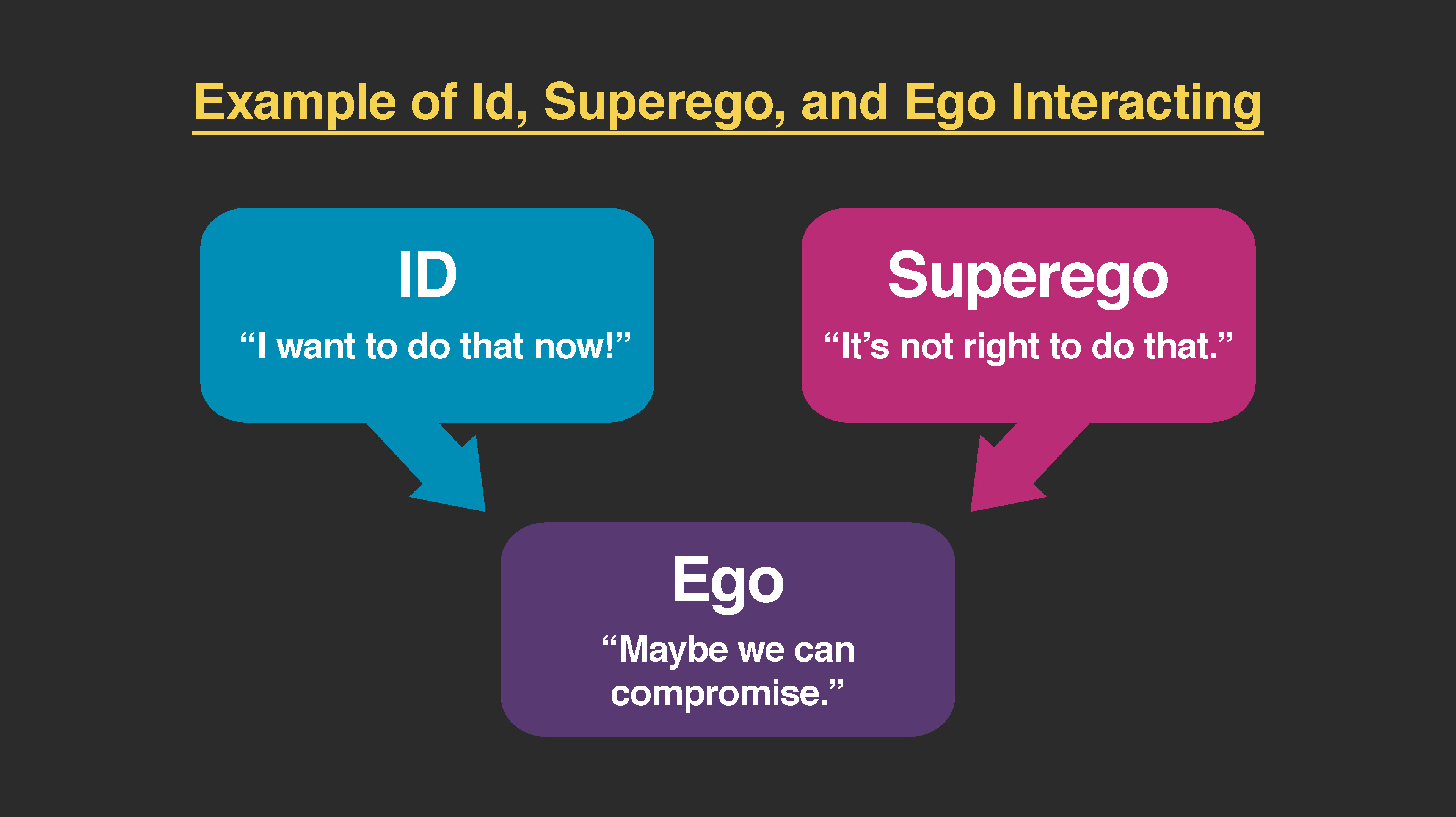

Freud argued that our personality develops from a conflict between two forces: our biological aggressive and pleasure-seeking drives versus our internal (socialized) control over these drives. Our personality is the result of our efforts to balance these two competing forces. Freud suggested that we can understand this by imagining three interacting systems within our minds. He called them the id, ego, and superego.

The unconscious id contains our most primitive drives or urges and is present from birth. It directs impulses for hunger, thirst and sex. Freud believed that the id operates on what he called the “pleasure principle,” in which the id seeks immediate gratification. Through social interactions with parents and others in a child’s environment, the ego and superego develop to help control the id. The superego develops as a child interacts with others, learning the social rules for right and wrong. The superego acts as our conscience; it is our moral compass that tells us how we should behave. It strives for perfection and judges our behavior, leading to feelings of pride or — when we fall short of the ideal — feelings of guilt. In contrast to the instinctual id and the rule-based superego, the ego is the rational part of our personality. It’s what Freud considered to be the self, and it is the part of our personality that is seen by others. Its job is to balance the demands of the id and superego in the context of reality; thus, it operates on what Freud called the “reality principle.” The ego helps the id satisfy its desires in a realistic way.

According to Freud, a person who has a strong ego, which can balance the demands of the id and the superego, has a healthy personality. Freud maintained that imbalances in the system can lead to neurosis (a tendency to experience negative emotions), anxiety disorders, or unhealthy behaviors. For example, a person who is dominated by their id might be narcissistic and impulsive. A person with a dominant superego might be controlled by feelings of guilt and deny themselves even socially acceptable pleasures; conversely, if the superego is weak or absent, a person might become a psychopath. An overly dominant superego might be seen in an over-controlled individual whose rational grasp on reality is so strong that he or she is unaware of emotional needs, or, in a neurotic who is overly defensive (overusing ego defense mechanisms).

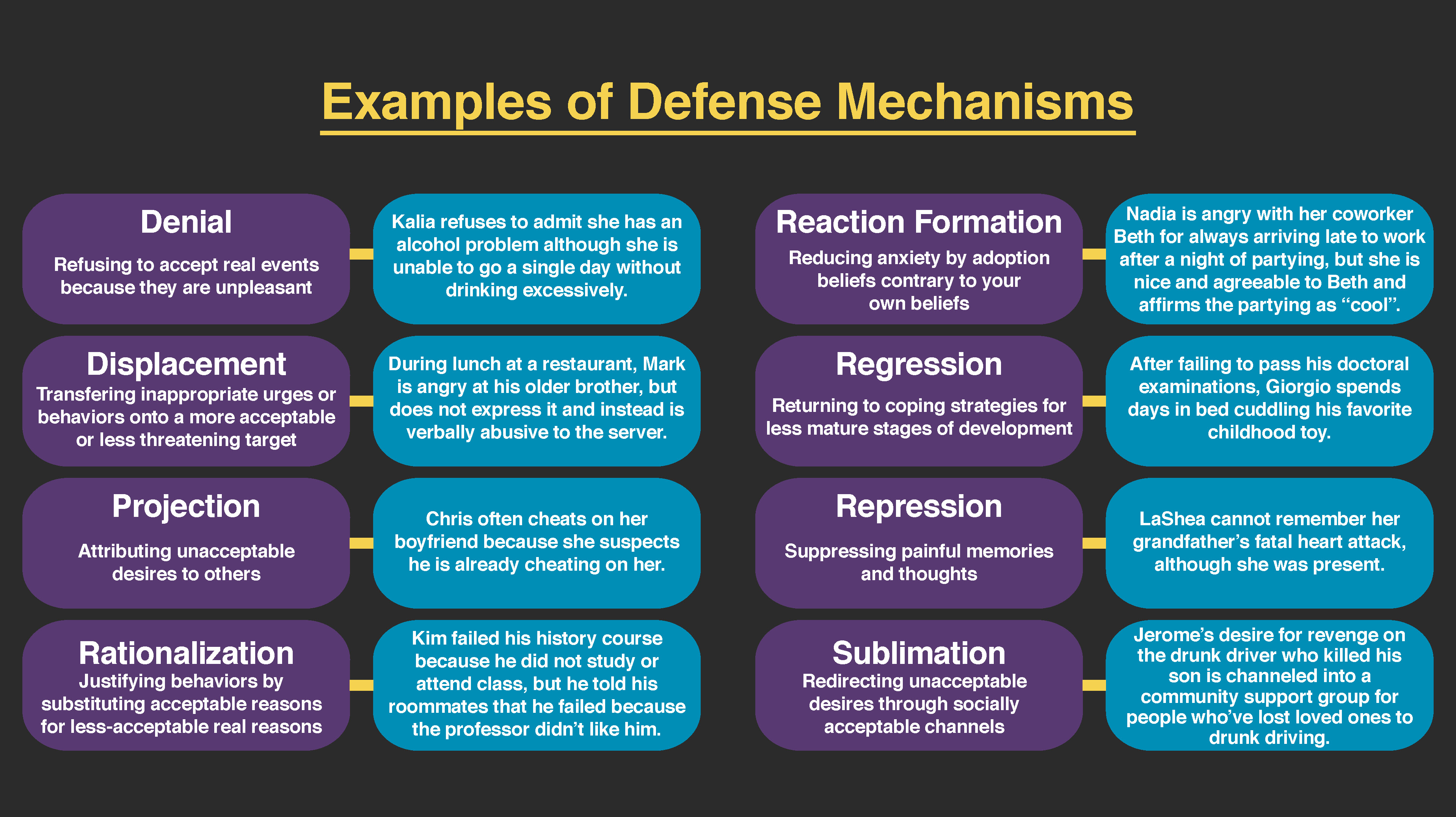

Freud believed that feelings of anxiety result from the ego’s inability to mediate the conflict between the id and superego. When this happens, Freud believed that the ego seeks to restore balance through various protective measures known as defense mechanisms, unconscious protective behaviors that aim to reduce anxiety. For example, let’s say Joe Smith is a high school football player. Deep down, Joe feels sexually attracted to males. His conscious belief is that being gay is immoral and that if he were gay, his family would disown him and he would be ostracized by his peers. Therefore, there is a conflict between his conscious beliefs (being gay is wrong and will result in being ostracized) and his unconscious urges (attraction to males). The idea that he might be gay causes Joe to have feelings of anxiety. How can he decrease his anxiety? Joe may find himself acting very “macho,” making gay jokes, and picking on a school peer who is gay. This way, Joe’s unconscious impulses are further submerged.

There are several different types of defense mechanisms. For instance, in repression, anxiety-causing memories from consciousness are blocked. If a memory is too overwhelming to deal with, it might be repressed and thus removed from conscious awareness. This repressed memory might cause symptoms in other areas.

Another defense mechanism is reaction formation, in which someone expresses feelings, thoughts and behaviors opposite to their inclinations. In the above example, Joe might make fun of a homosexual peer while himself being attracted to males. In regression, an individual acts much younger than their age. For example, a four-year-old child who resents the arrival of a newborn sibling may act like a baby and revert to drinking out of a bottle. In projection, a person refuses to acknowledge her own unconscious feelings and instead sees those feelings in someone else. Other defense mechanisms include rationalization, displacement and sublimation.

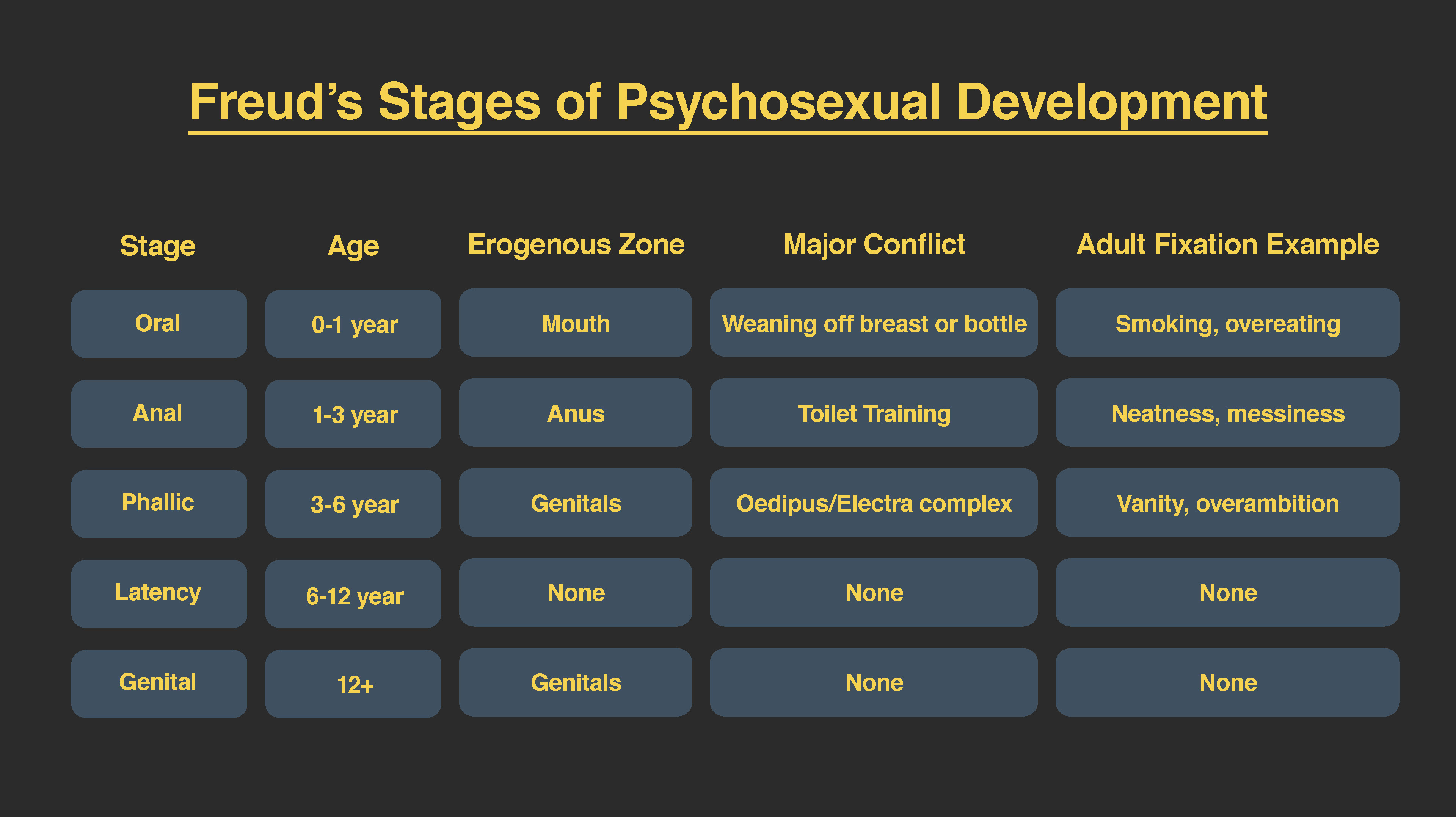

Freud believed that personality develops during early childhood: Childhood experiences shape our personalities as well as our behavior as adults. He asserted that we develop via a series of stages during childhood. Each of us must pass through these childhood stages, and if we do not have the proper nurturing and parenting during a stage, we will be stuck, or fixated, in that stage, even as adults. In each psychosexual stage of development, the child’s pleasure-seeking urges, coming from the id, are focused on a different area of the body, called an erogenous zone. The stages are oral, anal, phallic, latency, and genital.

The Neo-Freudians

- Neo-Freudian emphasis on social and cultural environment

- Vienna Psychoanalytical Society

- Adler’s social tasks: career and friendship and love

- Adler and birth order

- Erik Erikson and Anna Freud

- Erikson’s stages of personality and virtue

- 8-Stage Theory

Section Focus Question:

How did Adler and Erikson advance but also change the direction of Freudian psychology?

Key Terms:

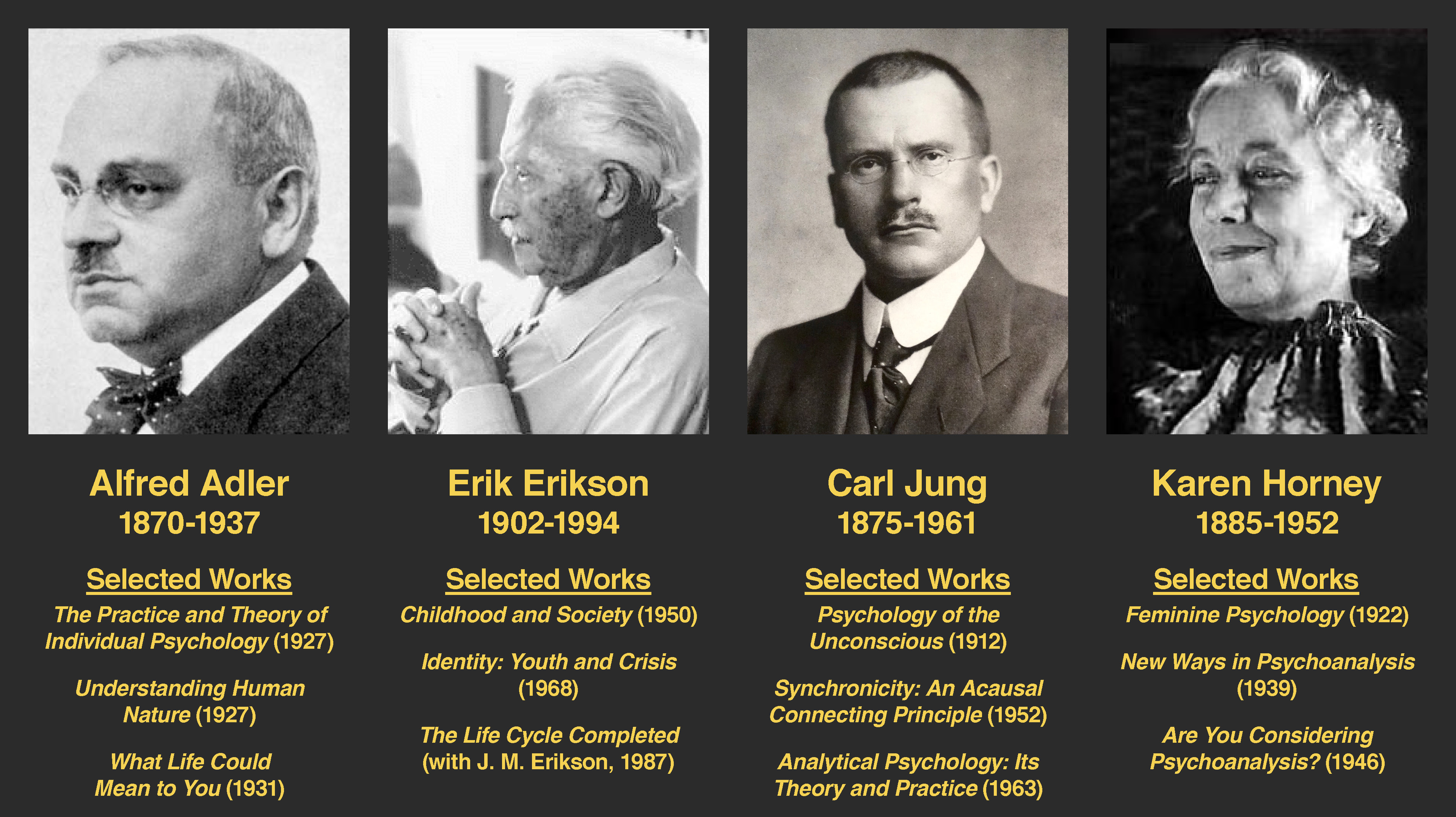

Freud attracted many followers who modified his ideas to create new theories about personality. These theorists, referred to as neo-Freudians, generally agreed with Freud that childhood experiences matter, but deemphasized sex and his theories about psychosexual stages of development, focusing more on the social environment and effects of culture on personality. Four notable neo-Freudians include Alfred Adler, Erik Erikson, Carl Jung and Karen Horney.

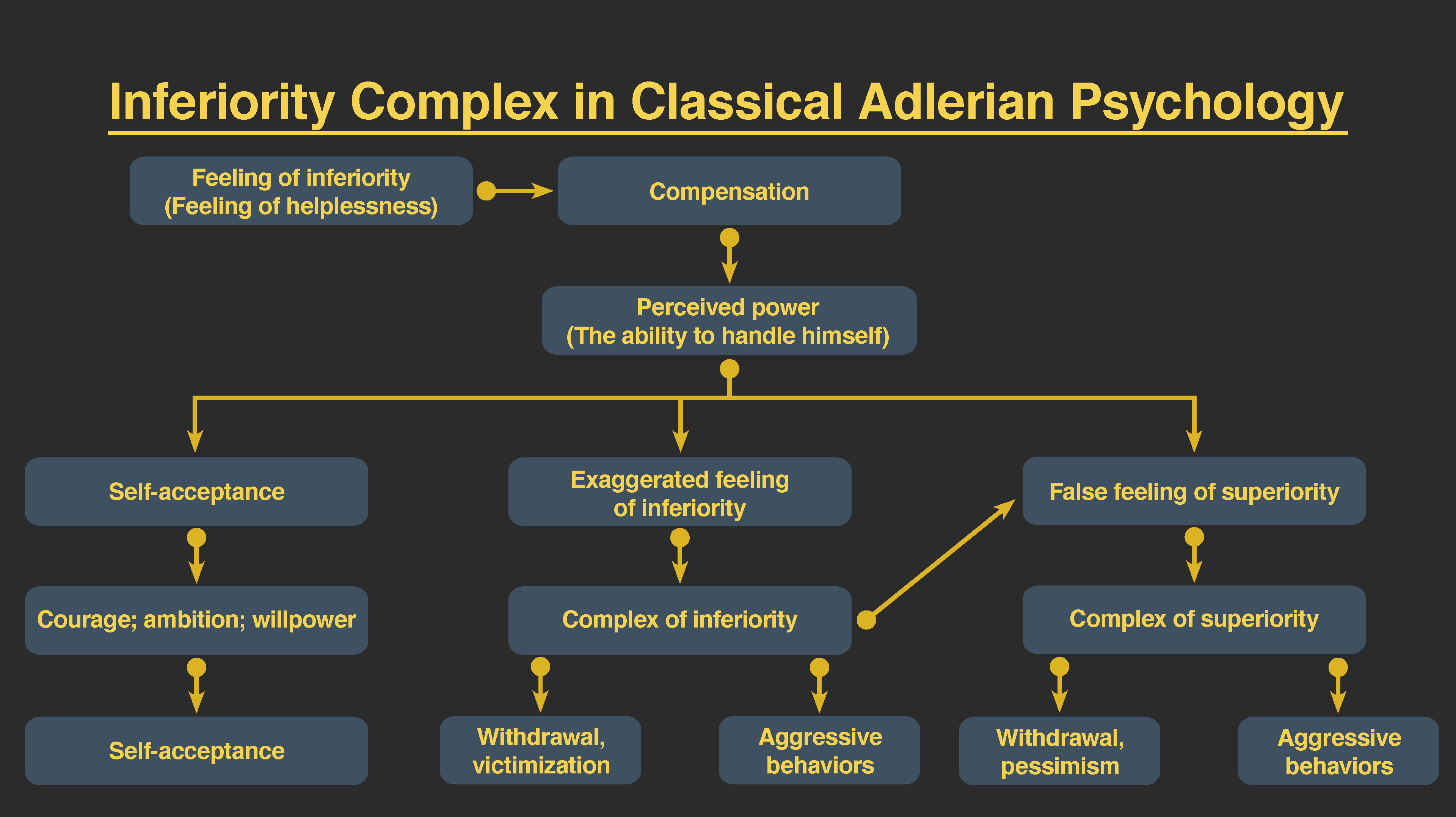

Alfred Adler (1870-1937) was a colleague of Freud, the first president of the Vienna Psychoanalytical Society (Freud’s inner circle of colleagues), and the first major theorist to break away from Freud. He subsequently founded a school of psychology called individual psychology, which focuses on our drive to compensate for feelings of inferiority. Adler proposed the concept of the inferiority complex. An inferiority complex refers to a person’s feelings that they lack worth and don’t measure up to the standards of others or of society. Adler’s ideas about inferiority represent a major difference between his thinking and Freud’s. Freud believed that we are motivated by sexual and aggressive urges, but Adler believed that feelings of inferiority in childhood are what drive people to attempt to gain superiority and that this striving is the force behind all of our thoughts, emotions, and behavior.

Adler also believed in the importance of social connections, seeing childhood development emerging through social development rather than the sexual stages Freud outlined. Adler noted the inter-relatedness of humanity and the need to work together for the betterment of all. He said, “The happiness of mankind lies in working together, in living as if each individual had set himself the task of contributing to the common welfare,” and the main goal of psychology was “to recognize the equal rights and equality of others.”

With these ideas, Adler identified three fundamental social tasks that all of us must experience: occupational tasks (careers), societal tasks (friendship) and love tasks (finding an intimate partner for a long-term relationship). Rather than focus on sexual or aggressive motives for behavior as Freud did, Adler focused on social motives. He also emphasized conscious rather than unconscious motivation, since he believed that the three fundamental social tasks are explicitly known and pursued. That is not to say that Adler did not also believe in unconscious processes — he did — but he felt that conscious processes were more important.

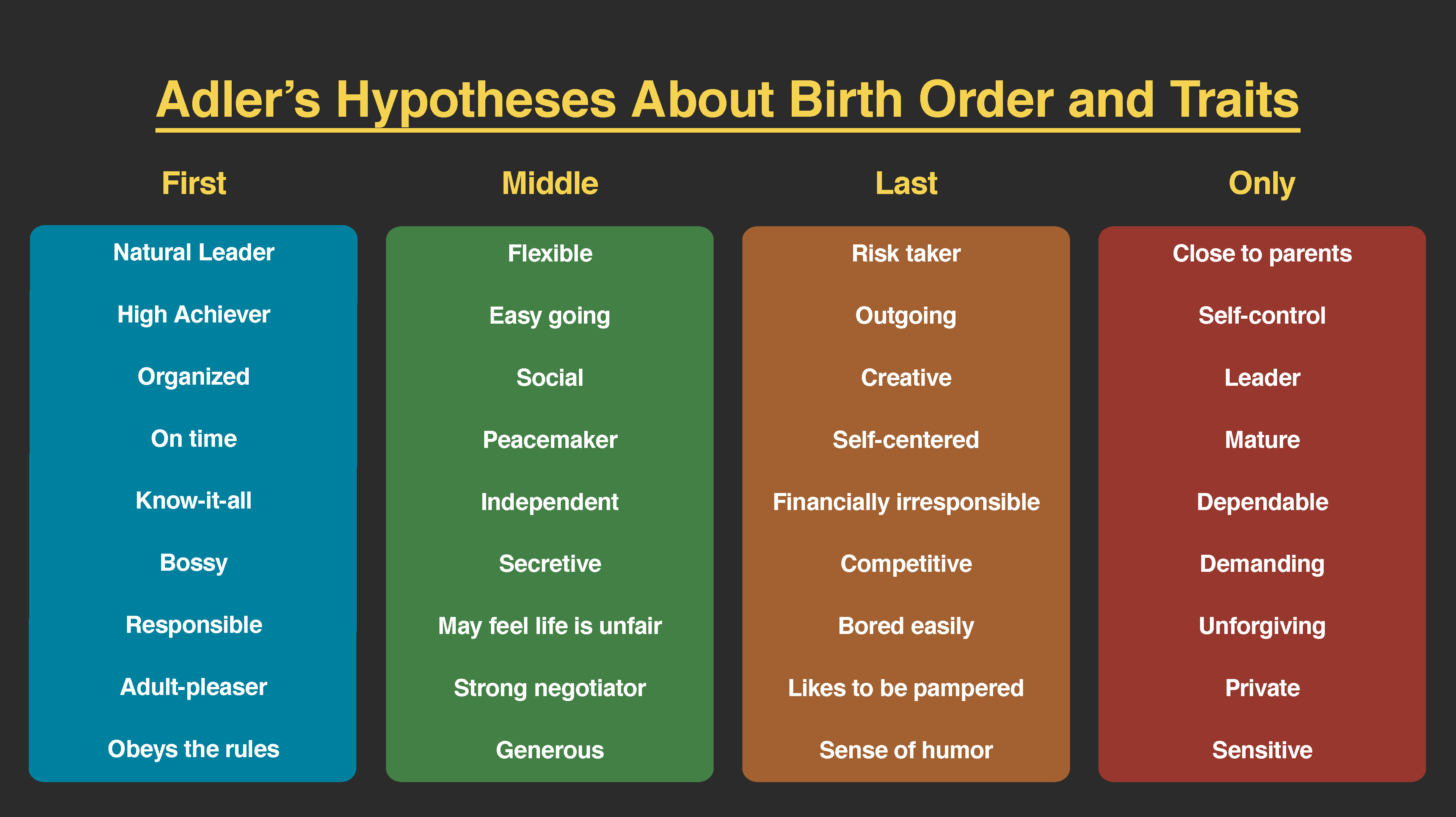

One of Adler’s major contributions to personality psychology was the idea that our birth order shapes our personality. He proposed those older siblings, who start out as the focus of their parent's attention but must share that attention once a new child joins the family, compensate by becoming overachievers. The youngest children, according to Adler, maybe spoiled, leaving the middle child with the opportunity to minimize the negative dynamics of the youngest and oldest children. Despite popular attention, research has not conclusively confirmed Adler’s hypotheses about birth order

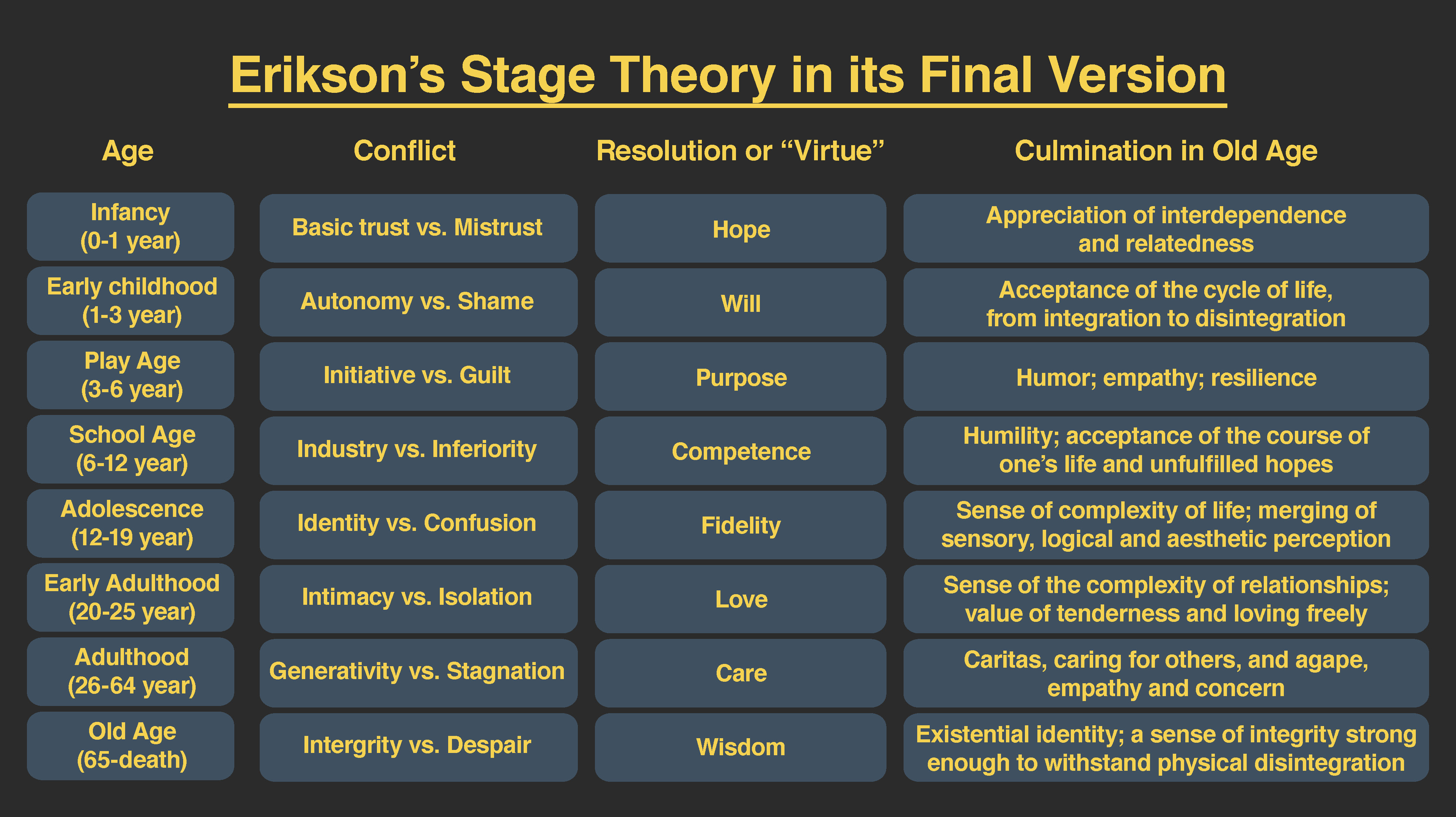

Erik Erikson (1902-1994) was an art school dropout with an uncertain future who met Freud’s daughter, Anna Freud, while he was tutoring the children of an American couple undergoing psychoanalysis in Vienna. It was Anna Freud who encouraged Erikson to study psychoanalysis. Erikson received his diploma from the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute in 1933, and as Nazism spread across Europe, he fled the country and immigrated to the United States that same year. Erikson later proposed a psychosocial theory of development, suggesting that an individual’s personality develops throughout the lifespan — a departure from Freud’s view that personality is fixed in early life. In his theory, Erikson emphasized the social relationships that are important at each stage of personality development, in contrast to Freud’s emphasis on sex. Erikson identified eight stages, each of which represents a conflict or developmental task. The development of a healthy personality and a sense of competence depend on the successful completion of each task.

Carl Jung (1875-1961) was a Swiss psychiatrist and protégé of Freud, who later split off from Freud and developed his own theory, which he called analytical psychology. The focus of analytical psychology is on working to balance opposing forces of conscious and unconscious thought, and experience within one’s personality. According to Jung, this work is a continuous learning process — mainly occurring in the second half of life — of becoming aware of unconscious elements and integrating them into consciousness.

- Goal of Jung’s analytical psychology

- Collective unconscious

- Jungian archetypes

- Symbols of the Jungian archetypes

- Jungian archetypes of the human genome

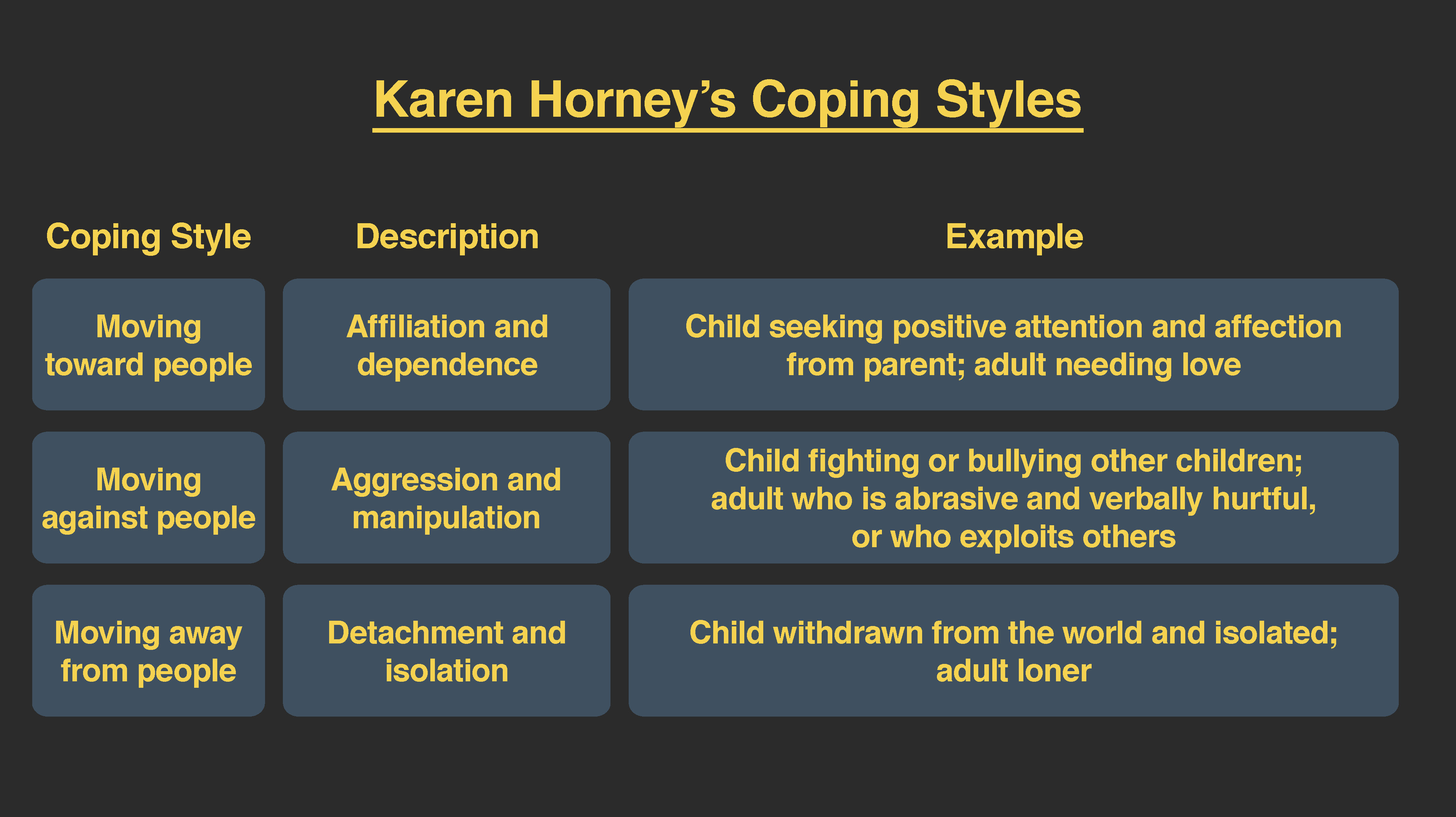

- Horney’s views on basic anxiety

- Horney’s 3 coping strategies for anxiety

Section Focus Question:

What were Jung’s and Horney’s ideas about anxiety and ways of dealing with it?

Key Terms:

Carl Jung was interested in exploring the collective unconscious. Jung’s split from Freud was based on two major disagreements. First, Jung, like Adler and Erikson, did not accept that the sexual drive was the primary motivator in a person’s mental life. Second, though Jung agreed with Freud’s concept of a personal unconscious, he thought it to be incomplete. In addition to the personal unconscious, Jung focused on the collective unconscious.

The collective unconscious is a universal version of the personal unconscious, holding mental patterns, or memory traces, which are common to all of us. These ancestral memories, which Jung called archetypes, are represented by universal themes in various cultures, as expressed through literature, art, and dreams. Jung said that these themes reflect common experiences of people the world over, such as facing death, becoming independent, and striving for mastery. Jung believed that through biology, each person is handed down the same themes and that the same types of symbols — such as the hero, the maiden, the sage and the trickster — are present in the folklore and fairy tales of every culture. In Jung’s view, the task of integrating these unconscious archetypal aspects of the self is part of the self-realization process in the second half of life. With this orientation toward self-realization, Jung parted ways with Freud’s belief that personality is determined solely by past events and anticipated the humanistic movement with its emphasis on self-actualization and orientation toward the future.

Jung proposed that human responses to archetypes are similar to instinctual responses in animals. One criticism of Jung is that there is no evidence that archetypes are biologically based or similar to animal instincts. Jung formulated his ideas about 100 years ago, and great advances have been made in the field of genetics since that time. We’ve found that human babies are born with certain capacities, including the ability to acquire language. However, we’ve also found that symbolic information (such as archetypes) is not encoded on the genome and that babies cannot decode symbolism, refuting the idea of a biological basis to archetypes. Rather than being seen as purely biological, more recent research suggests that archetypes emerge directly from our experiences and are reflections of linguistic or cultural characteristics. Today, most Jungian scholars believe that the collective unconscious and archetypes are based on both innate and environmental influences, with the differences being in the role and degree of each.

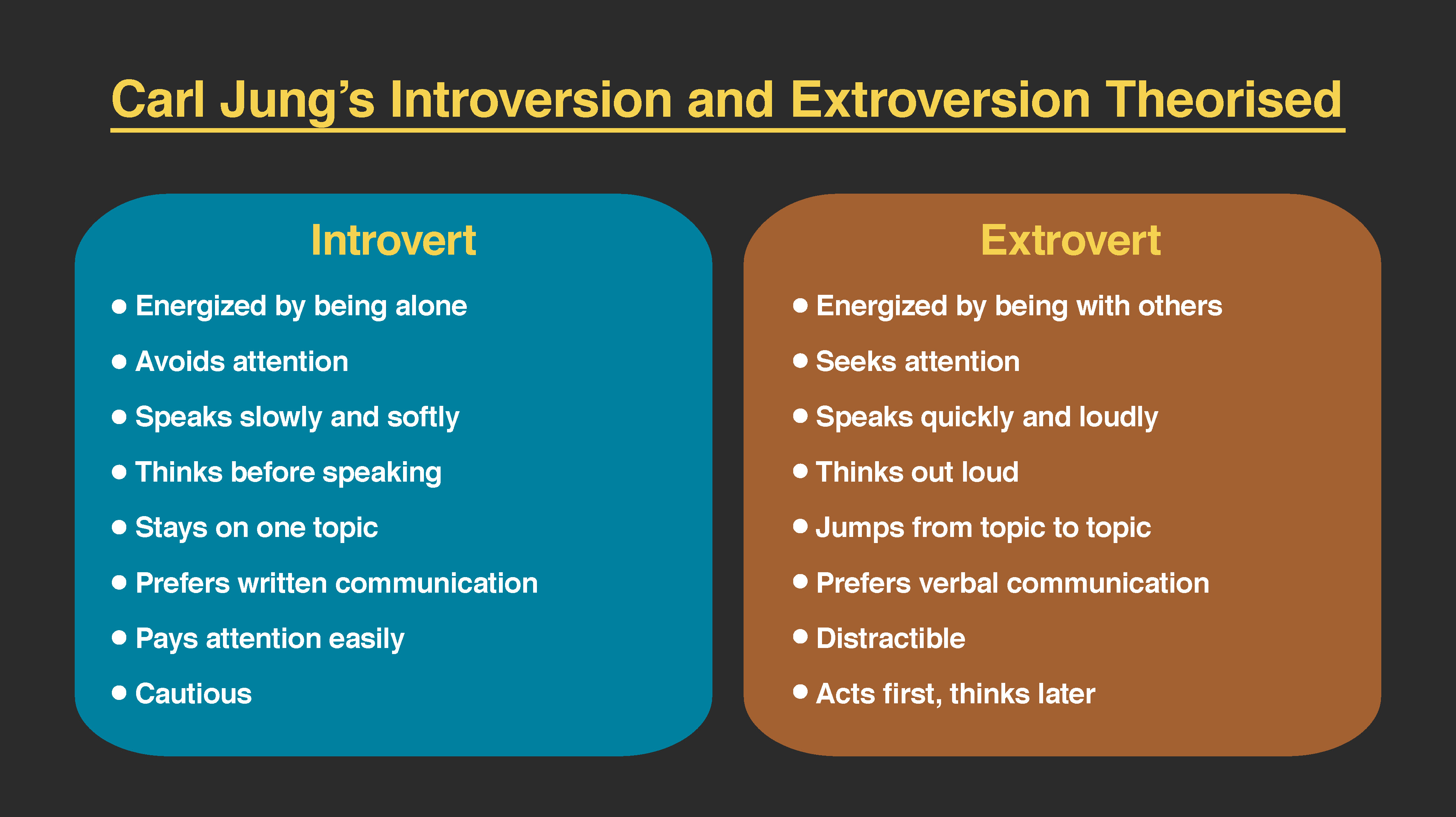

Jung also proposed two attitudes or approaches toward life: extroversion and introversion. These ideas are considered Jung’s most important contributions to the field of personality psychology, as almost all models of personality now include these concepts. If you are an extrovert, then you are a person who is energized by being outgoing and socially oriented: You derive your energy from being around others. If you are an introvert, then you are a person who may be quiet and reserved, or you may be social, but your energy is derived from your inner psychic activity. Jung believed a balance between extroversion and introversion best served the goal of self-realization.

Jung’s view of extroverted and introverted types serves as a basis for the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). This questionnaire describes a person’s degree of introversion versus extroversion, thinking versus feeling, intuition versus sensation, and judging versus perceiving.

Karen Horney (1885-1952) was one of the first women trained as a Freudian psychoanalyst. During the Great Depression, Horney moved from Germany to the United States and subsequently moved away from Freud’s teachings. Like Jung, Horney believed that each individual has the potential for self-realization and that the goal of psychoanalysis should be moving toward a healthy self rather than exploring early childhood patterns of dysfunction. Horney also disagreed with the Freudian idea that girls have penis envy and are jealous of male biological features. According to Horney, any jealousy is most likely culturally based, due to the greater privileges that males often have, meaning that the differences between men’s and women’s personalities are culturally based, not biologically based. She further suggested that men have womb envy because they cannot give birth.

Horney’s theories focused on the role of unconscious anxiety. She suggested that normal growth can be blocked by basic anxiety stemming from needs not being met, such as childhood experiences of loneliness and/or isolation. How do children learn to handle this anxiety? Horney suggested three styles of coping. The first coping style, moving toward people, relies on affiliation and dependence. These children become dependent on their parents and other caregivers in an effort to receive attention and affection, which provides relief from anxiety. When these children grow up, they tend to use this same coping strategy to deal with relationships, expressing an intense need for love and acceptance. The second coping style, moving against people, relies on aggression and assertiveness. Children with this coping style find that fighting is the best way to deal with an unhappy home situation, and they deal with their feelings of insecurity by bullying other children. As adults, people with this coping style tend to lash out with hurtful comments and exploit others. The third coping style, moving away from people, centers on detachment and isolation. These children handle their anxiety by withdrawing from the world. They need privacy and tend to be self-sufficient. When these children are adults, they continue to avoid such things as love and friendship, and they also tend to gravitate toward careers that require little interaction with others.

While Freud and the Neo-Freudians continue to influence the psychology of personality, the field has moved on to other areas of focus and explanations that are both observationally and experimentally based.