Humanistic, Biological, and Trait Perspectives

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

What were the perspectives on the psychology of personality that dominated psychology in the second half of the 20th century and how did they move beyond Freud?

- Post-Freud explanations of personality in the late 20th century

- 3 things that the humanist perspective focuses on

- Humanists moving beyond psychoanalytical and behaviorist perspectives

- Maslow’s emphasis on psychologically healthy people

- Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

- Famous people who are psychologically healthy

- Roger’s idea of “self-concept”

- Congruence between ideal and real selves

Section Focus Question:

What are the components of the humanist perspective?

Key Terms:

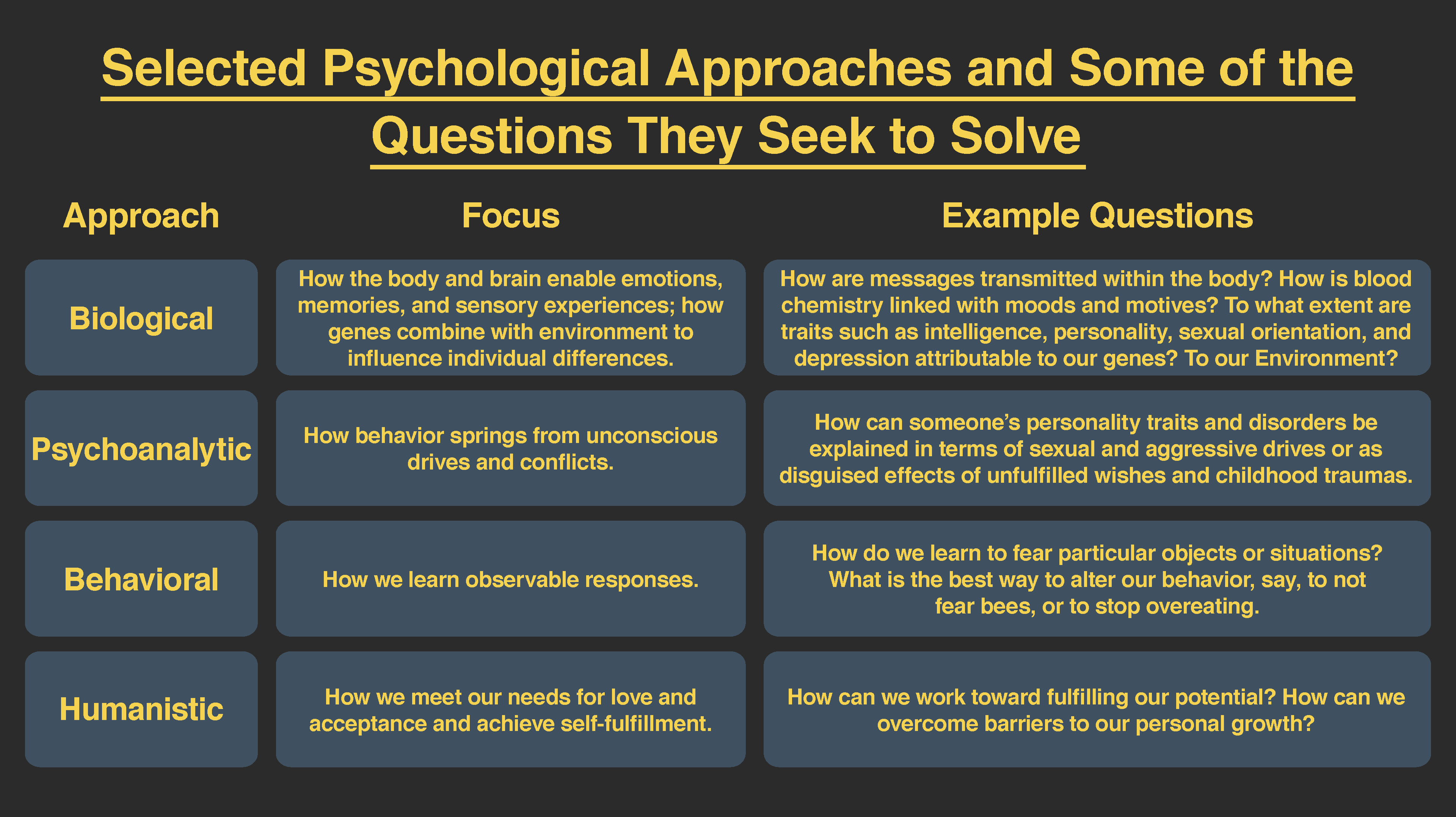

In the second half of the 20th century, psychologists began to move beyond Freud and explore other explanations for the development of personality. Naturally, these perspectives were influenced by other philosophical and experimental approaches, as well as a greater knowledge of the workings of the human brain.

The Humanistic Perspective

The humanistic perspective of personality focuses on psychological growth, free will and personal awareness. It takes a more positive outlook on human nature and is centered on how each person can achieve his or her individual potential.

Humanism is touted as a reaction both to the pessimistic determinism of psychoanalysis, with its emphasis on psychological disturbance, and to the behaviorists’ view of humans passively reacting to the environment, which has been criticized as making people out to be personality-less robots. It does not suggest that psychoanalytic, behaviorist and other points of view are incorrect but argues that these perspectives do not recognize the depth and meaning of human experience, and fail to recognize the innate capacity for self-directed change and transforming personal experiences. This perspective focuses on how healthy people develop.

Abraham Maslow (1908-1970), a pioneering humanist, studied people whom he considered to be healthy, creative and productive, including Albert Einstein, Eleanor Roosevelt, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln and others. Maslow found that such people share similar characteristics, such as being open, creative, loving, spontaneous, compassionate, concerned for others and accepting of themselves. Maslow's hierarchy of needs theory proposes that human beings have certain needs in common and that these needs must be met in a certain order. The highest need is the need for self-actualization, which is the achievement of our fullest potential.

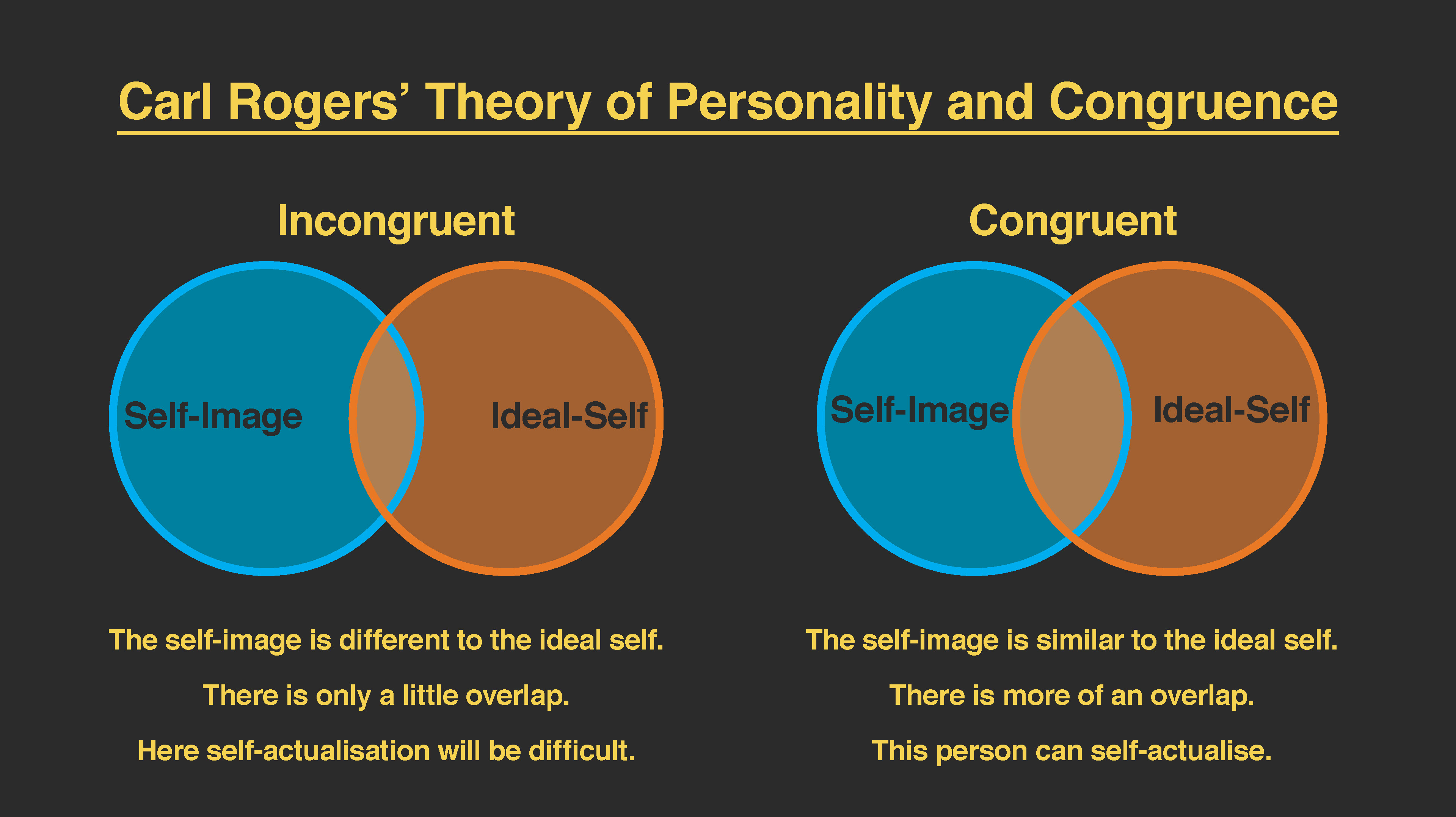

Carl Rogers (1902-1997), another humanistic theorist, proposed the idea in personality study of self-concept, our thoughts and feelings about ourselves. How would you respond to the question, “Who am I?” Your answer can show how you see yourself. If your response is primarily positive, then you tend to feel good about who you are, and you see the world as a safe and positive place. If your response is mainly negative, then you may feel unhappy with who you are.

Rogers further divided the self into two categories: the ideal self and the real self. The ideal self is the person that you would like to be; the real self is the person you actually are. Rogers focused on the idea that we need to achieve consistency between these two selves. We experience congruence when our thoughts about our real self and ideal self are very similar — in other words when our self-concept is accurate. High congruence leads to a greater sense of self-worth and a healthy, productive life. Parents can help their children achieve this by giving them unconditional positive regard, or unconditional love. According to Rogers (1980), “As persons are accepted and prized, they tend to develop a more caring attitude towards themselves.” Conversely, when there is a great discrepancy between our ideal and actual selves, we experience a state Rogers called incongruence, which can lead to maladjustment. Both Rogers’s and Maslow’s theories focus on individual choices and do not believe that biology is deterministic.

The Biological Perspective

- Conclusion of Minnesota Study of Twins Raise Apart

- Heritable personality characteristics

- Biological basis of temperament

- Reactivity and self-regulation

- Personality and body type

- Sheldon’s 3 body types

- Ectomorph personality

- Acceptance of Sheldon’s body types

Section Focus Question:

How much of our personality is in-born or dependent upon our biology?

Key Terms:

How much of our personality is in-born and biological, and how much is influenced by the environment and culture we are raised in? Psychologists who favor the biological approach believe that inherited predispositions, as well as physiological processes, can be used to explain differences in our personalities.

In the field of behavioral genetics, the Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart — a well-known study of the genetic basis for personality — conducted research with twins from 1979 to 1999. In studying 350 pairs of twins, including pairs of identical and fraternal twins reared together and apart, researchers found that identical twins, whether raised together or apart, have very similar personalities. These findings suggest the heritability of some personality traits. Heritability refers to the proportion of difference among people that is attributed to genetics. Some of the traits that the study reported as having more than a 0.50 heritability ratio include leadership, obedience to authority, a sense of well-being, alienation, resistance to stress and fearfulness. The implication is that some aspects of our personalities are largely controlled by genetics; however, it’s important to point out that traits are not determined by a single gene, but by a combination of many genes, as well as by epigenetic factors that control whether the genes are expressed.

Most contemporary psychologists believe temperament has a biological basis due to its appearance very early in our lives. Alexander Thomas and Stella Chess found that babies could be categorized into one of three temperaments: easy, difficult, or slow to warm up. However, environmental factors (family interactions, for example) and maturation can affect the ways in which children’s personalities are expressed.

Research suggests that there are two dimensions of our temperament that are important parts of our adult personality — reactivity and self-regulation. Reactivity refers to how we respond to new or challenging environmental stimuli; self-regulation refers to our ability to control that response. For example, one person may immediately respond to new stimuli with a high level of anxiety, while another barely notices it.

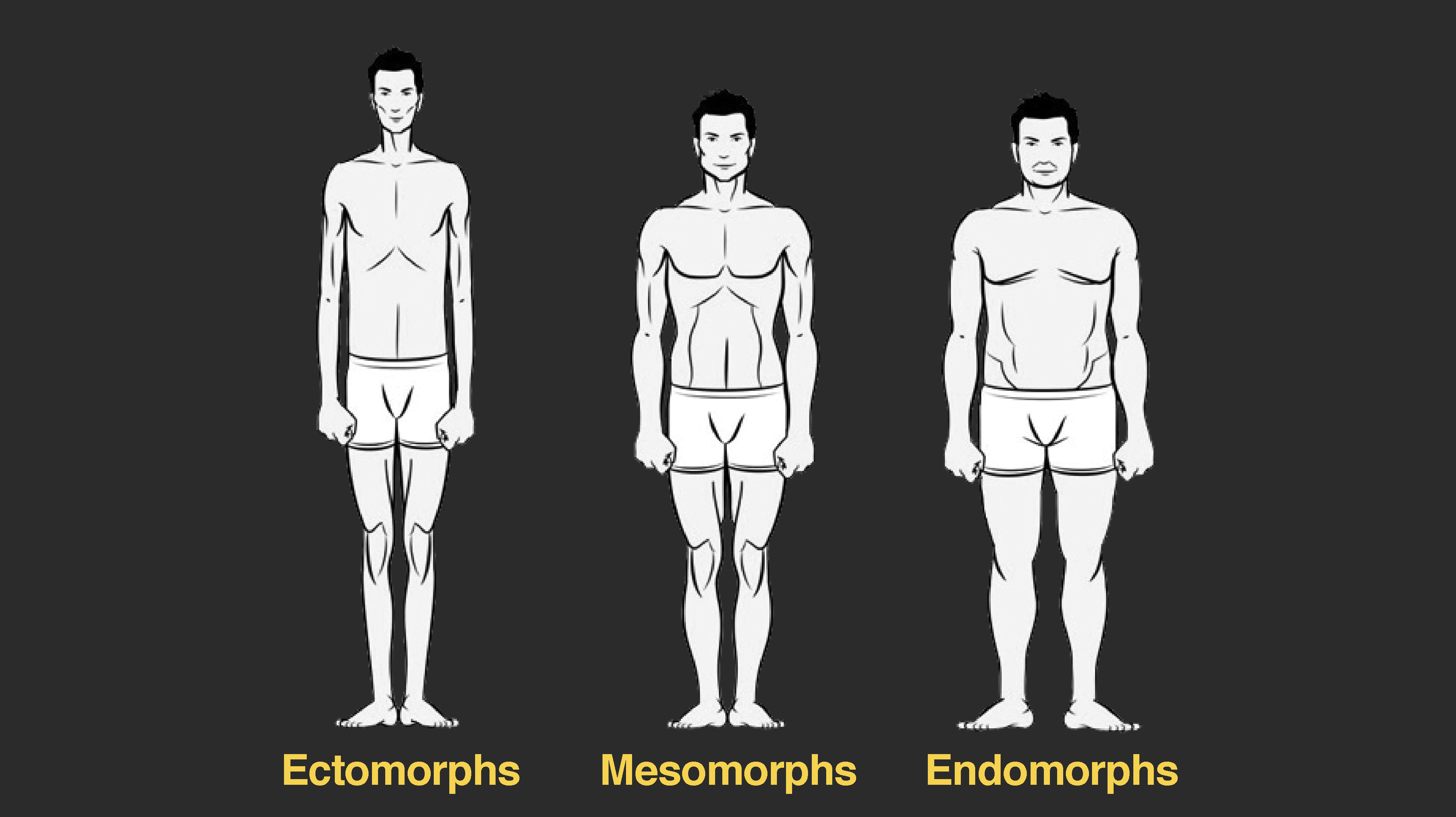

Is there an association between your body type and your temperament? The constitutional perspective, which examines the relationship between the structure of the human body and behavior, seeks to answer this question. The first comprehensive system of constitutional psychology was proposed by American psychologist William H. Sheldon. He believed that your body type can be linked to your personality. Sheldon’s life’s work was spent observing human bodies and temperaments. Based on his observations and interviews of hundreds of people, he proposed three body/personality types, which he called somatotypes.

The three somatotypes are ectomorphs, endomorphs, and mesomorphs. Ectomorphs are thin with a small bone structure and very little fat on their bodies. According to Sheldon, the ectomorph personality is anxious, self-conscious, artistic, thoughtful, quiet, and private. They enjoy intellectual stimulation and feel uncomfortable in social situations. Endomorphs are the opposite of ectomorphs. Endomorphs have narrow shoulders and wide hips and carry extra fat on their round bodies. Sheldon described endomorphs as being relaxed, comfortable, good-humored, even-tempered, sociable, and tolerant. Endomorphs enjoy affection and detest disapproval. The third somatotype is the mesomorph. This body type falls between the ectomorph and the endomorph. Mesomorphs have large bone structures, well-defined muscles, broad shoulders, narrow waists, and attractive, strong bodies. According to Sheldon, mesomorphs are adventurous, assertive, competitive and fearless. They are curious and enjoy trying new things, but can also be obnoxious and aggressive.

Sheldon’s method of somatotyping is not without criticism, as it has been considered largely subjective. More systematic and controlled research methods did not support his findings. Consequently, it’s not uncommon to see his theory labeled as pseudoscience. However, there have been studies supporting Sheldon involving correlations between somatotype, temperament, and children’s school performance, as well as pilot performance during wartime.

The Trait Perspective

- Definition of trait

- Central traits

- People have degrees of traits not certain exclusive traits

- Raymond Cattell and the assessment of traits

- Eysenck view of temperament

- Eysencks and extroversion

- Quadrants in the Eysencks’ two-factor model

- Traits in the Five-Factor Model

Section Focus Question:

What is a trait and how has a theory of personality developed around trait types?

Key Terms:

The trait perspective of personality is centered on identifying, describing and measuring the specific traits that make up human personality. By understanding these traits, researchers believe they can better comprehend the differences between individuals.

Trait theorists believe personality can be understood via the approach that all people have certain traits or characteristic ways of behaving. Do you tend to be sociable or shy? Passive or aggressive? Optimistic or pessimistic? Moody or even-tempered? Early trait theorists tried to describe all human personality traits. For example, one trait theorist, Gordon Allport, found 4,500 words in the English language that could describe people. He organized these personality traits into three categories: cardinal traits, central traits, and secondary traits. A cardinal trait is one that dominates your entire personality, like being greedy or very rustic, and is not very common. Central traits are those that make up our personalities generally, like loyal, kind, friendly or grouchy. Secondary traits are preferences or attitudes, like becoming angry instead of laughing when someone tickles you.

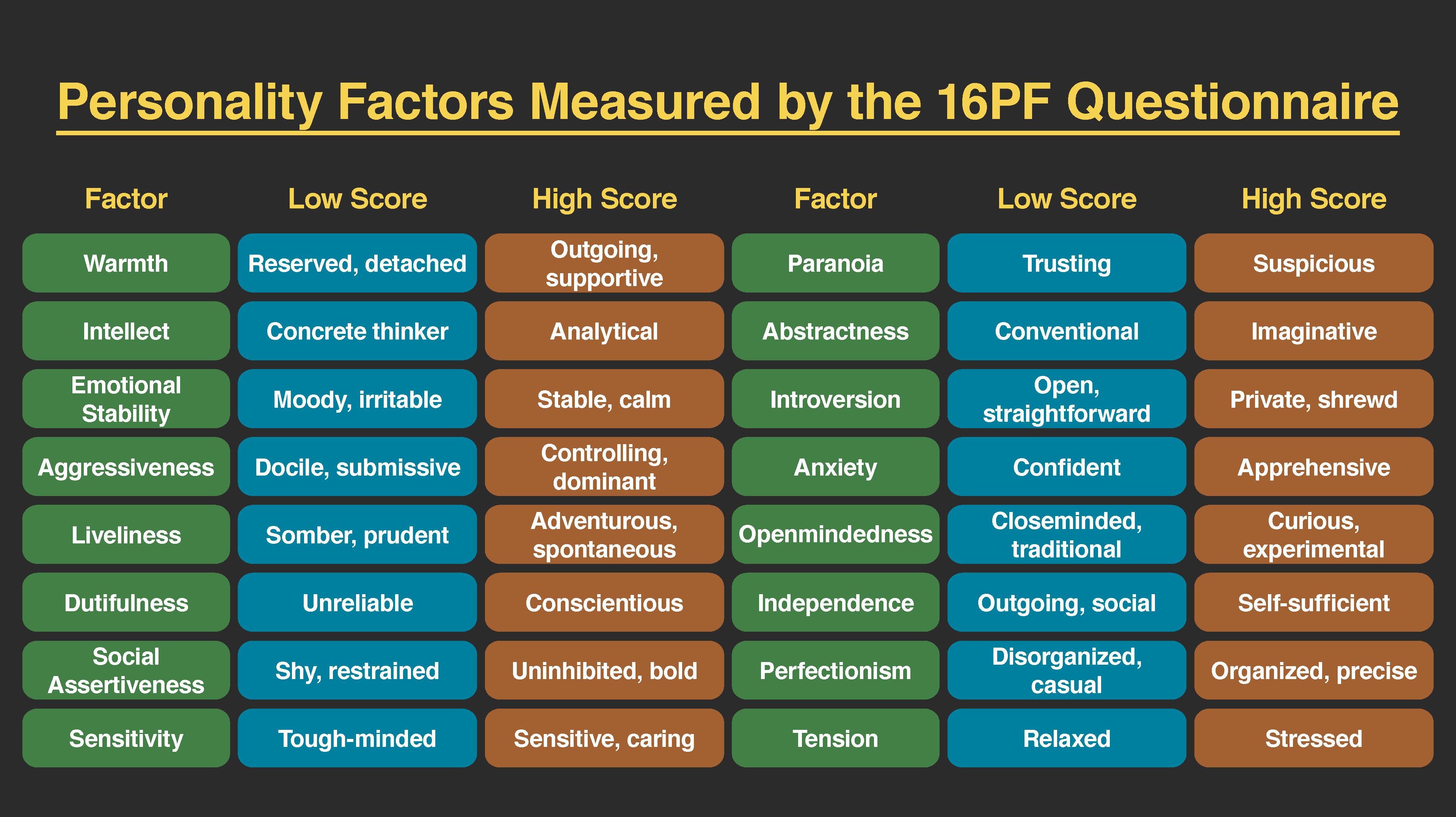

However, saying that a trait is either present or absent does not accurately reflect a person’s uniqueness, because all of our personalities are actually made up of the same traits; we differ only in the degree to which each trait is expressed. In an effort to make the list of traits more manageable, Raymond Cattell narrowed down the list to about 171 traits. Cattell identified 16 factors or dimensions of personality as seen in the table below. He developed a personality assessment based on these 16 factors, called the 16PF. Instead of a trait being present or absent, each dimension is scored over a continuum, from high to low. For example, your level of warmth describes how warm, caring, and nice to others you are. If you score low on this index, you tend to be more distant and cold. A high score on this index signifies you are supportive and comforting.

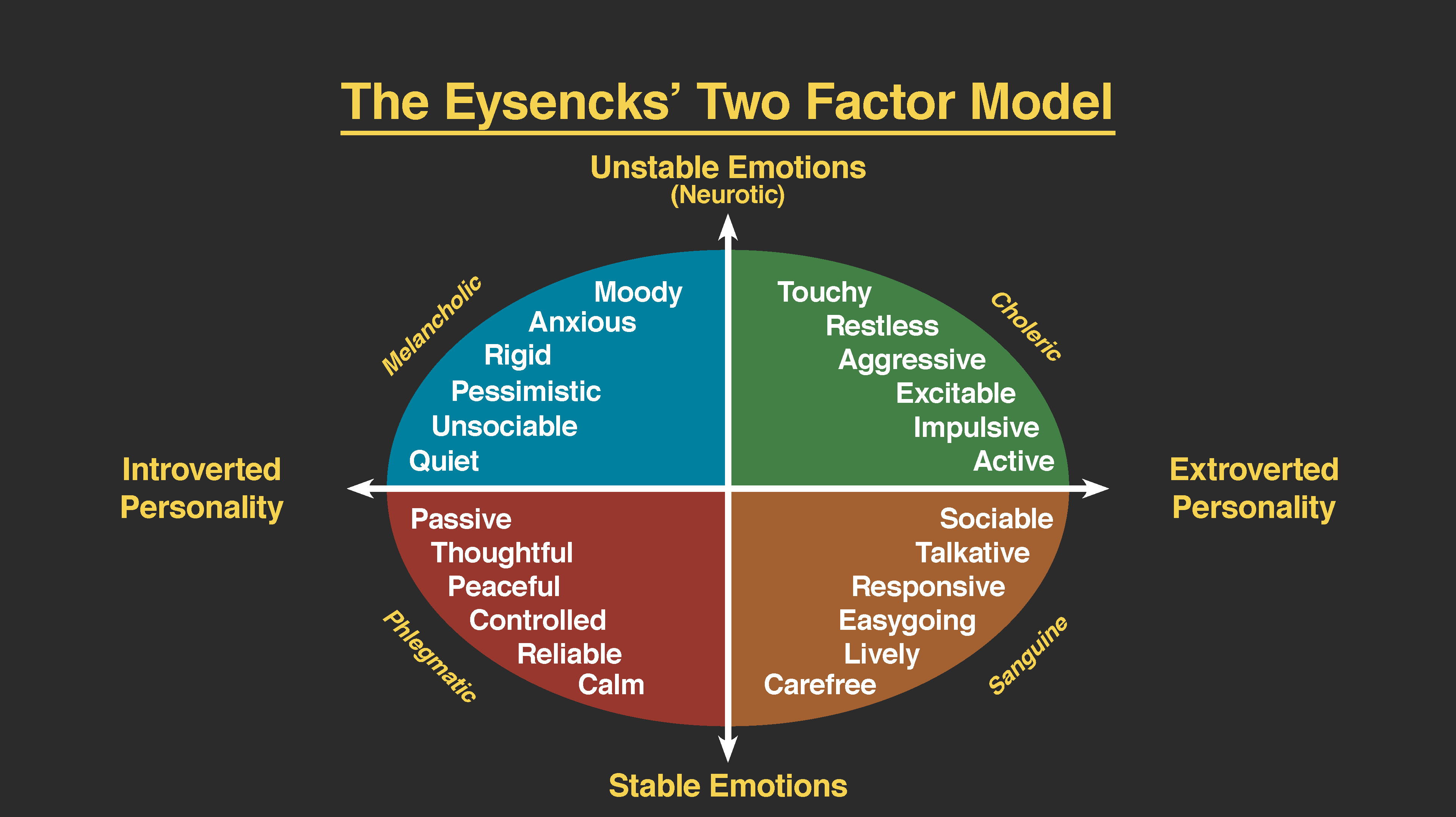

Psychologists Hans and Sybil Eysenck were personality theorists who focused on temperament. They believed personality is largely governed by biology. The Eysenck's viewed people as having two specific personality dimensions: extroversion/introversion and neuroticism/stability.

According to their theory, people high on the trait of extroversion are sociable and outgoing and readily connect with others, whereas people high on the trait of introversion have a higher need to be alone, engage in solitary behaviors, and limit their interactions with others. In the neuroticism/stability dimension, people high on neuroticism tend to be anxious; they tend to have an overactive sympathetic nervous system and, even with low stress, their bodies and emotional state tend to go into a flight-or-fight reaction. In contrast, people high on stability tend to need more stimulation to activate their flight-or-fight reaction and are considered more emotionally stable. Based on these two dimensions, Eysencks’ theory divides people into four quadrants.

Later, the Eysenck's added a third dimension: psychoticism versus superego control. In this dimension, people who are high on psychoticism tend to be independent thinkers, cold, nonconformists, impulsive, antisocial, and hostile, whereas people who are high on superego control tend to have high impulse control — they are more rustic, empathetic, cooperative, and conventional.

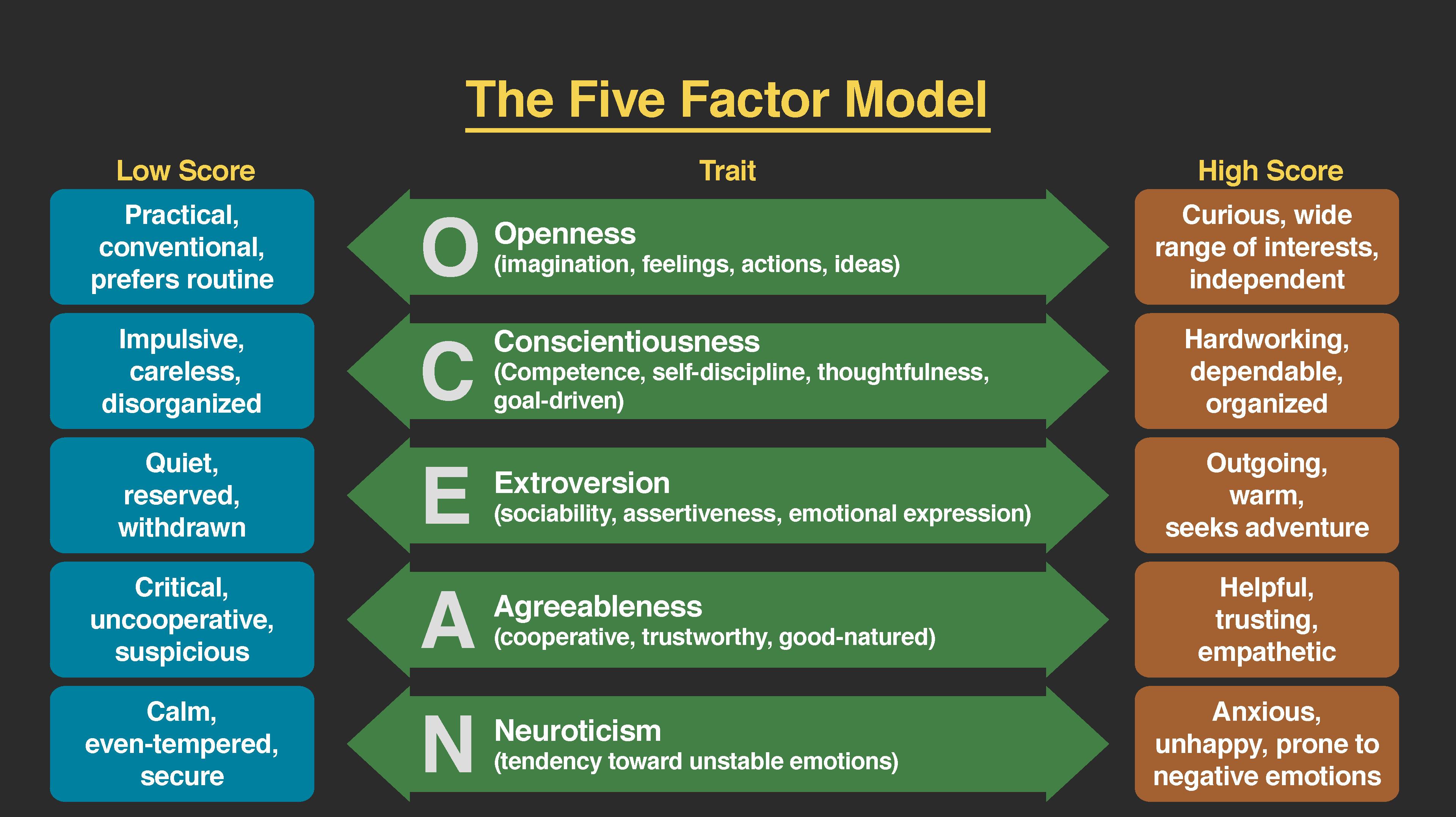

While Cattell’s 16 factors may be too broad, Eysenck’s two-factor system has been criticized for being too narrow. Another personality theory, called the Five Factor Model, effectively hits a middle ground, with its five factors referred to as the Big Five personality traits. It is the most popular theory in personality psychology today and the most accurate approximation of the basic trait dimensions. The five traits are openness to experience, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness and neuroticism. A helpful way to remember the traits is by using the mnemonic OCEAN.

In the Five Factor Model, each person has each trait, but they occur along a spectrum. Openness to experience is characterized by imagination, feelings, actions, and ideas. People who score high on this trait tend to be curious and have a wide range of interests. Conscientiousness is characterized by competence, self-discipline, thoughtfulness, and achievement-striving (goal-directed behavior). People who score high on this trait are hardworking and dependable. Numerous studies have found a positive correlation between conscientiousness and academic success. Extroversion is characterized by sociability, assertiveness, excitement-seeking, and emotional expression. People who score high on this trait are usually described as outgoing and warm. Not surprisingly, people who score high on both extroversion and openness are more likely to participate in adventure and risky sports due to their curiosity and excitement-seeking nature.

The fourth trait is agreeableness, which is the tendency to be pleasant, cooperative, trustworthy and good-natured. People who score low on agreeableness tend to be described as rude and uncooperative, yet one recent study reported that men who scored low on this trait actually earned more money than men who were considered more agreeable. The last of the Big Five traits is neuroticism, which is the tendency to experience negative emotions. People high on neuroticism tend to experience emotional instability and are characterized as angry, impulsive, and hostile. David Watson and Lee Anna Clark found that people reporting high levels of neuroticism also tend to report feeling anxious and unhappy. In contrast, people who score low in neuroticism tend to be calm and even-tempered.

The Big Five personality factors each represent a range between two extremes. In reality, most of us tend to lie somewhere midway along the continuum of each factor, rather than at polar ends. It’s important to note that the Big Five traits are relatively stable over our lifespan, with some tendency for the traits to increase or decrease slightly. Researchers have found that conscientiousness increases through young adulthood into middle age, as we become better able to manage our personal relationships and careers. Agreeableness also increases with age, peaking between 50 to 70 years. Neuroticism and extroversion tend to decline slightly with age. Additionally, The Big Five traits have been shown to exist across ethnicities, cultures and ages, and may have substantial biological and genetic components.