Deindustrialization and the Rise of the Service Economy

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

How did deindustrialization affect middle class America?

- Floating currency system, investors, and the economy

- Floating currencies exchange rate and currency markets

- Fixed currency system and gold reserve

- Foreign industries surpassing US production

- Nixon Presidency and loss of manufacture

Section Focus Question:

How did the American dollar affect the world economy in a way that was beneficial to American business in the post WWII era?

Key Terms:

In 1971, for the first time in almost 80 years, the United States imported more manufactured goods than it exported — a sign that industries in other parts of the world were surpassing America's capacity. That same year, President Nixon abruptly ended the guarantee that the United States would redeem, or buy, American dollars in gold. Thus, the United States dollar was no longer guaranteed to be the world's reserve currency, the currency that other nations would use to make international transactions.

Nixon's decision recognized the loss of America's former dominance as an exporter of manufactured goods. US businesses were changing, moving away from trade in tangible, material items toward more volatile financial instruments and the sale of currencies themselves. In 1970, for example, virtually all the commodities, or goods and services, traded on the futures market of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange were tangible products like grains or gold; by 2004, about three-quarters were intangible currencies or financial instruments.

Americans had been paying for all those imports of consumer goods and oil in dollars. If the foreign firms and governments that held those dollars now were to try to redeem, or buy, them in gold as promised, US gold reserves would be drained. But when the United States suddenly cancelled the promise of convertibility, all those stable exchange rates were thrown into flux.

Exchange rates now "floated" rather than being calculated against the dollar in a fixed, predictable ratio. The Swiss franc, for example, might be worth about 24 cents one month and 25 cents the next — and if you bought enough francs at the right moment, and sold them again in a hurry, you might make a considerable profit out of that single penny's difference.

On the other hand, if the slight change in value went the other way, your Swiss counterpart would come out ahead. Either way, the profits to be made from buying and selling money or financial instruments instead of goods or services depended on volatile prices and nonproductive investments.

- Effect of the rise of oil prices

- Correction between inflation and oil

- Productivity and the working class

- Republicans and lobbying effort of businesses

- Stagflation and the central bank

- Effect of inflation on middle and lower classes

- Connection between inflation and wages

Section Focus Question:

After 1970, increased productivity did not improve wages. How did an increase in the power of businesses influence this?

Key Terms:

Other signs of deindustrialization hit closer to ordinary people's jobs and homes. In the decades after World War II, productivity had increased — that is, each individual worker had produced more goods and services, and more profits for his employer. In response, employees had organized into unions and collectively pushed for wages and benefits to increase alongside profits.

In 1973 that annual growth in productivity slowed down dramatically; but growth in wages slowed even more, and essentially came to a halt. After the early 1970s, therefore, the majority of Americans could no longer expect to live better than their own parents even when producing more and working longer hours. While wages stalled out and unemployment increased dramatically, however, prices rose. In the 1970s, many oil-producing countries remade petroleum markets in line with their own economic and political interests. When the price of oil almost doubled, it boosted the cost of everything it touched, from the rush-hour commute to the wheat grown with petrochemicals on America's massive mechanized industrial farms. This combination of high inflation, on the one hand, with high unemployment and stagnant wages, on the other, contradicted economic common sense.

A new term, "stagflation," had to be coined for such an unprecedented development. The administrations of both Jimmy Carter and then Ronald Reagan had to choose whether to make unemployment or inflation their economic priority, since actions to fix one problem could be expected to exacerbate the other, at least in the short term. Both chose to address inflation rather than unemployment. A robust new economic philosophy thus aggressively sacrificed jobs and wages to reining in inflation.

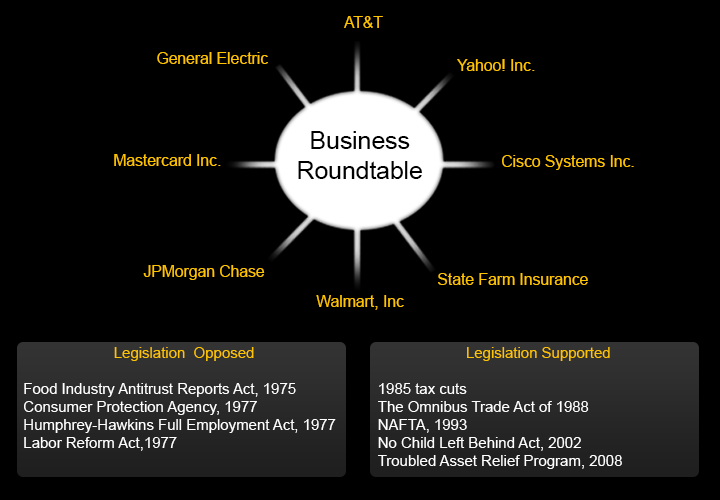

The new economic orthodoxy represented a social movement of financial and corporate actors. Organized into lobbying groups like the new Business Roundtable, the nation's largest corporations influenced tax policy in their favor and scored notable victories over organized labor in the 1970s and '80s. Concerned about the rising consumer protection movement, they also successfully championed legal changes that protected corporations from lawsuits and insulated them from responsibility for environmental destruction.

This newly influential movement opposed collective bargaining on the job and public safety nets in favor of strong private property rights and militant anti-communism. It argued for expanding some functions of government, like the military and prison systems, while limiting social services. This vision was popularized in part through foundations and think-tanks that drew their funding from corporate fortunes.

Their influence extended to the White House, where experts nurtured by this apparatus became influential economic advisors. The new economic thinking, moreover, became necessary to national electoral success by both parties. Democratic administrations as well as Republican ones promoted free trade, privatization, and financialization, or the process by which banking and trade in currencies becomes a dominant part of the economy. The changing economy, in other words, remade the political landscape.

- The 1980s and two wage earner households

- Decline of middle class wages and dual workplaces

- Women's dual workload

- Correlation of men to women wages

- Correlation between expansion of the prison system and unemployment

- Definition of "Welfare Queen"

- Middle class tax burden and social programs

- Middle classes and decline of income

- Reagan and job creation

- Drug control and the federal government

Section Focus Question:

How did working Americans manage to survive in an age of wage decline and dropping incomes?

Key Terms:

The result was a reversal of the policies that had increased and stabilized the middle class since World War II. The top 20 percent of households saw their incomes rise by almost 50 percent between 1979 and 2009; the bottom 20 percent saw theirs shrink by more than 7 percent.

Whereas a growing economy had once meant that incomes grew for all sectors of the population, after the early 1970s growth was concentrated in the very wealthiest households; middle-class incomes grew much less, and the poorest households lost ground. The deliberate dismantling of the New Deal after 1970 produced a level of inequality that had not been matched since right before the Great Depression. Inequality grew, moreover, both in good times and bad after 1970. More than half of all new jobs created in the Reagan years paid below the poverty line. During the long boom of the Clinton presidency (1992-2000), low unemployment did not mean that the most plentiful jobs could sustain families. And even with inflation under control, some of the most important items in family budgets became increasingly expensive. The costs of housing, transportation, health care, and a college education absorbed ever greater shares of family incomes.

Faced with flat wage rates and frequent lay-offs, but higher prices for the economic basics of stable family life, middle-class Americans had only a few routes open to them to maintain their standard of living and secure their children's futures. One widespread solution to the shrinking wage was borrowing.

While the owners of American business and industry were reluctant to pay their employees higher wages, they were increasingly eager to loan them money to make up the difference, now that they had invented ways to package and trade consumer debt around the world as a profitable new form of speculative currency. In essence, the surplus savings of countries like China could be recycled as credit for American households, whose continued consumption — with this borrowed money — stimulated production in other parts. Taking on record levels of household debt helped plug the gaps caused by stagnating wages and rising fixed costs, but by itself it was seldom enough to make up the difference.

The other major solution was to send another member of the household out to earn a paycheck. By 1980, the majority of households included 2 earners. Women's movement into the workforce offset the loss of household buying power through unemployment or stagnant wages. With more mothers working outside their homes some of their household work had to be replaced, and their husbands did not take up the slack. Even when husbands and wives both worked full time, women from the mid-1980s to the 2010s continued to do about twice as much housework as their husbands.

Instead, then, of dividing domestic labor equally, families that could afford it relied more on commercial service providers like restaurants, day-care centers, and nursing homes that hired minimum-wage employees. Some families paid other women to perform housework and childcare at home — increasingly, women who could be paid less than minimum wage because of their undocumented immigration status.

Across the board, from domestic workers to doctors, women continue to earn 20 to 30 percent less than men in the same occupations. A woman in 2008 had to earn a college degree to make the same as a man with just a high school diploma.

Conditions that strained middle-class families nonetheless rewarded many women with new access to meaningful, challenging, and even relatively well-paid work once new federal law prevented discrimination on the basis of sex. Poor women experienced these changes differently. Leaving the work of the home for paid work, in their cases, usually meant taking on stressful, insecure, low-paid jobs without benefits — the kinds of jobs that sectors like retail and fast-food relied upon for their record profits.

This sharp division in the kinds of jobs available was not confined to women workers. Despite all the faith placed in the "knowledge economy," none of the hottest job categories of the 2010s required a college education. The single biggest job category was retail clerk, for example, and the fastest-growing was home health aid. Both pay median wages below the federal poverty threshold for a family of 4.

Meanwhile, the business-backed free-market policies demanded cuts in the public investments that had raised many Americans — especially white Americans — into the middle class during the postwar period. To help sway public opinion against the kind of social safety nets offered by other industrial countries, conservatives found a useful scapegoat in the figure of the "welfare queen."

Resentment toward taxpayer-funded social programs for the poor grew as tax structures changed to rely more heavily on the middle class than on corporations or the wealthy. Once the Civil Rights Act of 1965 forced states to stop denying relief to black citizens while providing it for white ones, media coverage overwhelmingly represented aid recipients as African American.

In 1996 President Clinton signed a bipartisan bill that shed many mothers and children from the welfare rolls. But with these welfare moms largely entering minimum-wage work, even a full-time job couldn't raise them from poverty, especially as the federal minimum wage shrank in real terms to less than its value in 1970.

An equally drastic way to handle unemployment lay in the development of the largest carceral, or prison, state in human history. The United States began imprisoning its citizens at a rate unseen anywhere in the world at any time, a rate 6 to 10 times greater than any other industrial nation. In the 30 years between 1960 and 1990, for example, crime rates in the US and Germany were almost identical; yet over that period, the US incarcerated people at 8 times the rate of Germany.

Most of the growth in the incarcerated population came from new policies toward non-violent drug offenders. While research consistently demonstrates that virtually equal proportions of blacks and whites use and sell illegal drugs, some states convict black men at 20 to 50 times the rates of their white counterparts.

Even after sentences were served, the explosion in racially skewed nonviolent drug convictions created a pool of citizens who could be legally discriminated against in hiring and shut out of benefits like student loans, public housing, or food stamps. Meanwhile, communities across the country lobbied for prisons to be constructed where factories had fled and farms had collapsed. Taxpayer money could create jobs in building prisons and guarding inmates in rural, largely white towns.